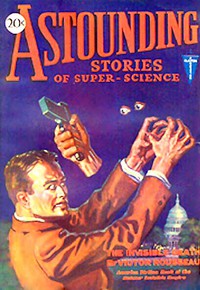

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930, Various [feel good books to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930, Various [feel good books to read .TXT] 📗». Author Various

"Then I was conscious of Drayle's presence. A brown silk dressing gown fell shapelessly about his spare frame and smoke from his cigarette rose in a quivering blue-white stream. Ward spied him at the same moment and stepped forward with quick outstretched hands. I remember the flame of adoring zeal in the youngster's eyes as he tried to speak. At length he managed to stammer some congratulatory phrases while Drayle clapped him affectionately on the back.

"Then Drayle turned to Farrel to ask him how he enjoyed the trip. Farrel grinned and said, 'Fine! It was like a dream, sir! First I'm in one place and then I'm in another and I don't know nothing about how I got there. But I could do with a drink, sir. I ain't used to them airyplanes much.'

"Drayle accepted the hint and suggested that we all celebrate. He gave instructions over a desk telephone and almost immediately a man entered with a small service wagon containing a wide assortment of liquors and glasses. When we had all been served, Ward asked somewhat hesitantly if he might propose a toast. 'To Dr. Drayle, the greatest scientist of all time!'

e were of course, already somewhat drunk with excitement as we lifted our glasses. But Drayle would not have it.

"'Let me amend that,' he said. 'Let[126] us drink to the future of science.'

"'Sure!' said Farrel, very promptly. I think he was somewhat uncertain about 'toast,' but he clung hopefully to the word 'drink.'

"We had raised our glasses again when Drayle, who was facing the door, dropped his. It struck the floor with a little crash and the liquor spattered my ankles. Drayle whispered 'Great God!' I saw in the doorway another Farrel. He was grimy, disheveled, his clothing was torn, and his expression ugly; but his identity with 'Harry' was unescapable. For an instant I suspected Drayle of trickery, of perpetrating some fiendishly elaborate hoax. And then I heard Mrs. Farrel scream, heard the newcomer cry, 'Mary,' and saw two men staring at each other in bewilderment.

"The explanation burst upon me with a horrible suddenness. Farrel had been reconstructed in each of Drayle's distant laboratories, and there stood before us two identities each equally authentic, each the legal husband of the woman who, a few hours previously, had imagined herself a widow. The situation was fantastic, nightmarish, unbelievable and undeniable. My head reeled with the fearful possibilities.

"Drayle was the first to recover his poise. He opened a door leading into an adjoining room and motioned for us all to enter. That is, all but the police. He left them wisely with their liquor. 'Finish it,' he advised them. 'You see no one has been killed.'

hey were not quite satisfied, but neither were they certain what they ought to do, and for once displayed common sense by doing nothing. When the door closed after us I saw that Buchannon, the Washington laboratory assistant, was with us. He must have arrived with the second Farrel, although I had not observed him during the confusion attending the former's unexpected appearance. But Drayle had noted him and now seized his shoulders. 'Explain!' he demanded.

"Buchannon's face went white and he shrank under the clutch of Drayle's fingers. Beyond them I saw the two twinlike men standing beside Mrs. Farrel, surveying each other with incredulous recognition and distaste.

"'Explain!' roared Drayle, and tightened his grasp.

"'I thought you said Washington, Chief.' His voice was not convincing. I didn't believe him, nor did Drayle.

"'You lie!' he raged, and floored the man with his fist.

"In a way I couldn't help feeling sorry for the chap. It must have been a frightful temptation to participate in the experiment and I suppose he had not forseen the consequences. But I began to have a glimmering of the magnificent possibilities of the invention for purposes far beyond Drayle's intent. For, I asked myself, why, if such a machine could produce two human identities, why not a score, a hundred, a thousand? The best of the race could be multiplied indefinitely and man could make man at last, literally out of the dust of the earth. The virtue of instantaneous transmission which had been Drayle's aim sank into insignificance beside it. I fancied a race of supermen thus created. And I still believe, Sergeant, that the chance for the world's greatest happiness is sealed within that box you guard. But its first fruits were tragic."

The historian shifted his position on the bench so as to escape the sun that was now reflected dazzlingly by the polished steel casket.

rayle did not glance again at his disobedient lieutenant. He was concerned with the problem of the extra man, or, I should say, an extra man, for both were equal. Never before in the history of the world had two men been absolutely identical. They were, of course, one in thought, possessions and rights, physical attributes and appearance. Mrs. Farrel, as they were beginning to realize, was the wife of both. And I have an un[127]worthy suspicion that the red-headed young woman, after she recovered from the shock, was not entirely displeased. The two men, however, finding that each had an arm about her waist, were regarding each other in a way that foretold trouble. Both spoke at the same time and in the same words.

"'Take your hands off my wife!'

"And I think they would have attacked each other then if Drayle hadn't intervened. He said, 'Sit down! All of you!' in so peremptory a voice that we obeyed him.

"'Now,' he went on, 'pay attention to me. I think you realize the situation. The question is, what we shall do about it?' He pointed an accusing finger at the Farrel from Washington. 'You were not authorized to exist; properly we should retransmit you, and without reassembling you would simply cease to be.'

"The man addressed looked terrified. 'It would be murder!' he protested.

"'Would it?' Drayle inquired of me.

"I told him that it could not be proved inasmuch as there would be no corpus delicti and hence nothing on which to base a charge.

"But the Washington Farrel seemed to have more than an academic interest in the question and grew obstinate.

"'Nothing doing!' he announced emphatically. 'Here I am and here I stay. I started from this place this morning and now I'm back, and as for that big ape over there I don't know nothing about him—except he'll be dead damn soon if he don't keep away from my wife.'

he other Drayle-made man leaped up at this, and again I expected violence. But Buchannon flung himself between, and they subsided, muttering.

"'Very well, then,' Drayle continued, when the room was quiet, 'here is another solution. We can, as you realize, duplicate Mrs. Farrel, and I will double your present possessions.'

"This time it was Mrs. Farrel who was dissatisfied. 'You ain't talking to me,' she informed Drayle. 'Me stand naked in front of all them lamps and get turned into smoke? Not me!' A smile spread over her face and her eyes twinkled with deviltry. 'I didn't never think I'd be in one of them triangles like in the movies, and with my own husbands, but seein' I am, I'm all for keeping them both. Then I might know where one of them was some of the time.'

"But neither of the men took to this idea and the problem appeared increasingly complex. I proposed that the survivor be determined by lot, but this suggestion won no support from anyone. Again the two men spoke at the same instant and in the same words. It was like a carefully rehearsed chorus. 'I know my rights, and I ain't going to be gypped out of them!'

"It was at this point that Drayle attempted bribery. He offered fifty thousand dollars to the man who would abandon Mrs. Farrel. But this scheme fell through because both men sought the opportunity and Mrs. Farrel objected volubly.

"So in the end Drayle promised each of them the same amount as a price for silence and left the matter of their relationships to their own settlement.

was skeptical of the success of the plan but could offer nothing better. So I drew up a release as legally binding as I knew how to make it in a case without precedent. I remember thinking that if the matter ever came into court the judge would be as much at a loss as I was.

"Our troubles, though, didn't spring from that source. Each of the three parties accepted the arrangement eagerly and Drayle dismissed them with a hand-shake, a wish for luck and a check for fifty thousand dollars each. It's very nice to be wealthy, you know.

"Afterward, we went out and paid off the police. Perhaps that's stating it too bluntly. I mean that Drayle thanked them for their zealous atten[128]tion to his interests, regretted that they had been unnecessarily inconvenienced and treated that they would not take amiss a small token of his appreciation of their devotion to duty. Then he shook hands with them both and I believe I saw a yellow bill transferred on each occasion. At any rate the officers saluted smartly and left.

"Of course I was impatient to question Drayle, but I could see that he was desperately fatigued. So I departed.

"Next morning I found my worst fears exceeded by the events of the night. The three Farrels who had left us in apparently amiable spirits had proceeded to the home of Mrs. and the original Mr. Farrel. There the argument of who was to leave had been resumed. Both men were, of course, of the same mind. Whether both desired to stay or flee I would not presume to say. But an acrimonious dispute led to physical hostilities, and while Mrs. Farrel, according to accounts, cheered them on, they literally fought to the death. Being equally capable, there was naturally, barring interruption, no other possible outcome. I can well believe they employed the same tactics, swung the same blows, and died at the same instant.

"Mrs. Farrel, after carefully retrieving both of her husbands' checks, told a great deal of the story. As might be expected, nobody believed the yarn except our profound federal law makers. They welcomed an opportunity to investigate an outsider for a change and had all of us before a committee.

"Finally the Congress of these United States of America, plus the sagacious Supreme Court, decided that my client wasn't guilty of anything, but that he mustn't do it again. At least that was the gist of it. I recollect that I offered a defense of psycopathic neuroticism.

"As a result of the obiter dictum and a resolution by both Houses Assembled Drayle's invention was sealed, dated and placed under guard. That's its history, Sergeant."

he white-haired old gentleman picked up the high silk hat that added a final touch of distinction to his tall figure, and looked about him as if trying to recall something. At last the idea came.

"By the way," he inquired suddenly, "didn't I have an extraordinarily obnoxious grandson with me when I came?"

The attentive auditor was vastly startled. He surveyed the great hall rapidly, but reflected before he answered.

"No, sir—I mean he ain't no more'n average! But I reckon we'd better find him, anyhow."

His glance had satisfied the sergeant that at least the object of his charge was safe and his men still vigilant. "I'll be back in a minute," he informed them. "Don't let nothin' happen."

"Bring us something more'n a breath," pleaded the corporal, disrespectfully.

The sergeant had already set off at a brisk pace with the story teller. For several minutes as they rushed from room to room the hunt was unrewarded.

"I think, sir," said the sergeant, "we'd better look in the natural history division. There is stuffed animals in there that the kids is fond of."

"You're probably right," the patriarch gasped as he struggled to maintain the gait set by the younger man. "I might have known he didn't really want to hear the story."

"They never do," answered the other over his shoulder. "I'll bet that's him down there on the next floor."

he two searchers had emerged upon a wide

Comments (0)