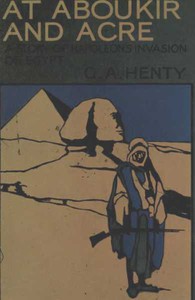

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt, G. A. Henty [top 10 inspirational books .txt] 📗

- Author: G. A. Henty

Book online «At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt, G. A. Henty [top 10 inspirational books .txt] 📗». Author G. A. Henty

The sailors, who had already guessed that his errand was urgent by the speed at which Edgar dashed down to the boat, stretched themselves to their oars and rowed as if racing, and met the Turkish boats a quarter of a mile from the shore.

"I am sent by the commander-in-chief, Sir Sidney Smith, to order you to row round to the mole and land there. Order the men to row their hardest. Every moment is of consequence. The French are on the point of entering the town."

At once the flotilla of boats changed its course, the soldiers cheered, filled with the excitement of the moment, and the sailors tugged at their oars; and, headed by the gig, in ten minutes the boats reached the landing-place by the mole, and as the troops leaped out, Edgar, burning with impatience and anxiety, led them to the breach. It was still held. Some of the Turks, as the French entered the tower, had been seized with a panic and fled, but a few remained at their post. While some hurled down stones from above on to the column ascending the breach, others met them hand to hand at the top of the heap. Here Sir Sidney Smith himself took his place with three or four of his officers and the handful of blue-jackets.

The combat was a desperate one. The swords of the officers, the cutlasses of the sailors, the pikes of the Turks,[Pg 228] clashed against the bayonets of the French. Soon an important ally arrived. The news had speedily reached Djezzar that Sir Sidney and his officers were themselves defending the breach. The old pasha had hitherto taken no personal part in the conflict, but had, as was the Turkish custom, remained seated on his divan every day, receiving reports from his officers, giving audience to the soldiers who brought in the heads of enemies, and rewarding them for their valour. Now, however, he leapt to his feet, seized his sabre, and ran to the breach, shouting to the soldiers to follow him. On his arrival at the scene of conflict he rushed forward and pulled Sir Sidney and his officers forcibly back from the front line.

"You must not throw away your lives," he said; "if my English friends are killed, all is lost."

Fortunately, the shouts of the pasha, as he ran, caused a number of soldiers to follow him, and these now threw themselves into the fray, and maintained the defence until Edgar ran up with the soldiers who had just landed.

The reinforcements, as they arrived, were greeted with enthusiastic shouts from the inhabitants, numbers of whom, men and women, had assembled at the landing-place on hearing of the approach of the boats. The garrison, reanimated by the succour, ran also to the breach, and the combat was now so stoutly maintained that Sir Sidney was able to retire with the pasha, to whom he proposed that one of the newly-arrived regiments, a thousand strong, armed with bayonets and disciplined in the European method, should make a sally, take the enemy in flank, or compel them to draw off.

The pasha at once assented, a gate was opened, and the Turks rushed out. Their orders were to carry the enemy's nearest trench, and to shift the gabions and fascines to the[Pg 229] outward side, and to maintain themselves there. The new arrivals, however, were not yet inured to fighting, and as the French batteries opened upon them, and the soldiers, leaping on to the parapets, poured volley after volley into their midst, they faltered, and presently turned and fled back to the gate, their retreat being protected by heavy discharges of grape from the 68-pounders in the port. The sortie, however, had its effect. The French had suffered heavily from the flanking fire as soon as they had shown themselves on the parapet, and the assaulting column, knowing from the din of battle that a serious sortie had been made, fell back from the breach, their retreat being hastened by the discharge of a number of hand-grenades by a midshipman of the Theseus on the top of the tower.

But the assault was not yet over. Napoleon, with several of his generals and a group of aides-de-camp, had been watching the fight from an eminence known as Richard Cœur de Lion's Mount, and had been compelled to shift their position several times by shells thrown among them from the ships. Their movements were clearly visible with a field-glass. Bonaparte was seen to wave his hand violently, and an aide-de-camp galloped off at the top of his speed. Edgar, who was standing near Sir Sidney Smith, was watching them through a telescope, and had informed Sir Sidney of what he had seen.

"Doubtless he is ordering up reinforcements. We shall have more fighting yet."

He then held a consultation with the pasha, who proposed that this time they should carry out a favourite Turkish method of defence—allow the enemy to enter the town, and then fall upon them. The steps were removed from the walls near the tower, so that the French, when they issued from the top of the ruined building, would be[Pg 230] obliged to follow along the wall, and to descend by those leading into the pasha's garden. Here two hundred Albanians, the survivors of a corps a thousand strong who had greatly distinguished themselves in the sorties, were stationed, while all the garrison that could be spared from other points, together with the newly-arrived troops, were close at hand. The Turks were withdrawn from the breach and tower, and the attack was confidently awaited.

It came just before sunset, when a massive column advanced to the breach. No resistance was offered. They soon appeared at the top of the ruin, which was now no higher than the wall itself, and moved along the rampart. When they came to the steps leading into the pasha's garden, a portion of them descended, while the main body moved farther on, and made their way by other steps down into the town. Then suddenly the silence that had reigned was broken by an outburst of wild shouts and volleys of musketry, while from the head of every street leading into the open space into which the French had descended, the Turkish troops burst out. In the pasha's garden the Albanians threw themselves, sabre in one hand and dagger in the other, upon the party there, scarce one of whom succeeded in escaping, General Rombaud, who commanded, being among the slain, and General Lazeley being carried off wounded.

The din of battle at the main scene of conflict was heightened by the babel of shouts and screams that rose throughout the town. No word whatever of the intention to allow the French to enter the place had been spoken, for it was known that the French had emissaries in the place, who would in some way contrive to inform them of what was going on there, and the success of the plan would have been imperilled had the intentions of the de[Pg 231]fenders been made known to the French. The latter fought with their usual determination and valour, but were unable to withstand the fury with which they were attacked from all sides, and step by step were driven back to the breach. Thus, after twenty-four hours of fighting, the position of the parties remained unaltered.

Bonaparte, in person, had taken part in the assault, and when the troops entered the town had taken up his place at the top of the tower. Kleber, who commanded the assault, had fought with his accustomed bravery at the head of his troops, and for a time, animated by his voice and example, his soldiers had resisted the fiercest efforts of the Turks. But even his efforts could not for long maintain the unequal conflict. As the troops fell back along the walls towards the breach, the guns from elevated positions mowed them down, many of the shot striking the group round Bonaparte himself. He remained still and immovable, until almost dragged away, seeming to be petrified by this terrible disaster, when he deemed that, after all his sacrifices and losses, success was at last within his grasp.

During the siege he had lost five thousand men. The hospitals were crowded with sick. The tribesmen had ceased to send in provisions. Even should he succeed in taking the town after another assault, his force would be so far reduced as to be incapable of further action. Its strength had already fallen from sixteen thousand to eight thousand men. Ten of his generals had been killed. Of his eight aides-de-camp, four had been killed and two severely wounded.

The next evening the Turkish regiment that had made a sortie on the night of their landing, but had been unable to face the tremendous fire poured upon them, begged that they might be allowed to go out again in order to retrieve themselves.[Pg 232]

Permission was given, and their colonel was told to make himself master of the nearest line of the enemies' trenches, and to hold them as directed on the occasion of his previous sortie. The work was gallantly done. Unheeding the enemy's fire the Turks dashed forward with loud shouts, leapt into the trenches, and bayonetted their defenders; but instead of setting to work to move the materials of the parapet across to the other side, carried away by their enthusiasm they rushed forward, and burst their way into the second parallel. So furiously did they fight that Kleber's division, which was again advancing to make a final attempt to carry the breach, had to be diverted from its object to resist the impetuous Turks. For three hours the conflict raged, and although the assailants were greatly outnumbered they held their ground nobly. Large numbers fell upon both sides, but at last the Turks were forced to fall back again into the town.

The desperate valour with which they had just fought hand to hand without any advantage of position showed the French troops how hopeless was the task before them; and Kleber's grenadiers, who had been victors in unnumbered battles, now positively refused to attempt the ascent of the fatal breach again.

Receiving news the next day that three French frigates had just arrived off Caesarea, Sir Sidney determined to go in pursuit of them, but the pasha was so unwilling that the whole force of British should depart that he sent off the Theseus with two Turkish frigates that had accompanied the vessels bringing the troops.

The voyage was an unfortunate one. Captain Miller, as the supply of shot and shell on board the men-of-war was almost exhausted, had for some time kept his men, when not otherwise engaged at work, collecting French shell[Pg 233] which had fallen, without bursting, in the town. A number of these he had fitted with fresh fuses, and a party of sailors were engaged in preparing the others for service, when from some unknown cause one of them exploded, and this was instantly followed by the bursting of seventy others. The men had been at work on the fore part of the poop, near Captain Miller's cabin, and he and twenty-five men were at once killed and the vessel set on fire in five places. Mr. England, the first lieutenant, at once set the crew to work, and by great exertions succeeded in extinguishing the flames. He then continued the voyage, and drove the three French frigates to sea.

The loss of Captain Miller, who had been indefatigable in his exertions during the siege, was a great blow to Sir Sidney Smith. He appointed Lieutenant Canes, who had been in charge of the Tigre during his absence on shore, to the command of the Theseus, and transferred Lieutenant England to the place of first lieutenant of the Tigre.

It was generally felt that after the tremendous loss he suffered in the last of the eleven assaults made by the French that Napoleon could no longer continue the siege. Not only had the numerical loss been enormous in proportion to the strength of the army, but it had fallen upon his best troops. The artillery had suffered terribly, the grenadiers had been almost annihilated, and as the assaults had always been headed by picked regiments, the backbone of the army was gone. It was soon ascertained indeed that Napoleon was sending great convoys of sick, wounded, and stores down the coast, and on the 20th the siege was raised, and the French marched away.

[Pg 234]

CHAPTER XIII. AN INDEPENDENT COMMAND.The departure of the French had been hastened by the rapidly-increasing discontent and insubordination among the troops. During the later days of the siege Sir Sidney Smith had issued great numbers of printed copies of a

Comments (0)