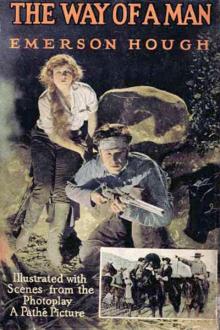

The Way of a Man, Emerson Hough [ebook reader macos .TXT] 📗

- Author: Emerson Hough

- Performer: -

Book online «The Way of a Man, Emerson Hough [ebook reader macos .TXT] 📗». Author Emerson Hough

I looked at him and made no motion. It seemed to me go unspeakably sad, so incredible, that one should be so unbelievably underestimated.

"Now, finally," resumed Colonel Meriwether, after a time, ceasing his walking up and down, "I must close up what remains between you and me. My daughter said to me that you wanted to see me on some business matter. Of course you had some reason for coming out here."

"That was my only reason for coming," I rejoined. "I wanted to see you upon an important business matter. I was sent here by the last message my father gave any one—by the last words he spoke in his life. He told me I should come to you."

"Well, well, if you have any favor to ask of me, out with it, and let us end it all at one sitting."

"Sir," I said, "I would see you damned in hell before I would ask a crust or a cup of water of you, though I were starving and burning. I have heard enough."

"Orderly!" he called out. "Show this man to the gate."

It was at last borne in upon me that I must leave without any word from Ellen. She was hedged about by all the stern and cold machinery of an Army Post, out of whose calculations I was left as much as though I belonged to a different world. I cannot express what this meant for me. For weeks now, for months, indeed, we two had been together each hour of the day. I had come to expect her greeting in the morning, to turn to her a thousand times in the day with some query or answer. I had made no plan from which she was absent. I had come to accept myself, with her, as fit part of an appointed and happy scheme. Now, in a twinkling, all that had been subverted. I was robbed of her exquisite dependence upon me, of those tender defects of nature that rendered her most dear. I was to miss now her fineness, her weakness and trustfulness, which had been a continual delight. I could no longer see her eyes nor touch her hands, nor sit silent at her feet, dreaming of days to come. Her voice was gone from my listening ears. Always I waited to hear her footstep, but it came no longer, rustling in the grasses. It seemed to me that by some hard decree I had been deprived of all my senses; for not one was left which did not crave and cry aloud for her.

It was thus that I, dulled, bereft; I, having lived, now dead; I, late free, now bound again, turned away sullenly, and began my journey back to the life I had known before I met her.

As I passed East by the Denver stage, I met hurrying throngs always coming westward, a wavelike migration of population now even denser than it had been the preceding spring. It was as Colonel Meriwether said, the wagons almost touched from the Platte to the Rockies. They came on, a vast, continuous stream of hope, confidence and youth. I, who stemmed that current, alone was unlike it in all ways.

One thing only quickened my laggard heart, and that was the all prevalent talk of war. The debates of Lincoln and Douglas, the consequences of Lincoln's possible election, the growing dissensions in the Army over Buchanan's practically overt acts of war—these made the sole topics of conversation. I heard my own section, my own State, criticised bitterly, and all Southerners called traitors to that flag I had seen flying over the frontiers of the West. At times, I say, these things caused my blood to stir once more, though perhaps it was not all through patriotism.

At last, after weeks of travel across a disturbed country, I finally reached the angry hive of political dissension at Washington. Here I was near home, but did not tarry, and passed thence by stage to Leesburg, in Virginia; and so finally came back into our little valley and the quiet town of Wallingford. I had gone away the victim of misfortune; I returned home with a broken word and an unfinished promise and a shaken heart. That was my return.

I got me a horse at Wallingford barns, and rode out to Cowles' Farms. At the gate I halted and looked in over the wide lawns. It seemed to me I noted a change in them as in myself. The grass was unkempt, the flower beds showed little attention. The very seats upon the distant gallery seemed unfamiliar, as though arranged by some careless hand. I opened the gate for myself, rode up to the old stoop and dismounted, for the first time in my life there without a boy to take my horse. I walked slowly up the steps to the great front door of the old house. No servant came to meet me, grinning. I, grandson of the man who built that house, my father's home and mine, lifted the brazen knocker of the door and heard no footstep anticipate my knock. The place sounded empty.

Finally there came a shuffling footfall and the door was opened, but there stood before me no one that I recognized. It was a smallish, oldish, grayish man who opened the door and smiled in query at me.

"I am John Cowles, sir," I said, hesitating. "Yourself I do not seem to know—"

"My name is Halliday, Mr. Cowles," he replied. A flush of humiliation came to my face.

"I should know you. You were my father's creditor."

"Yes, sir, my firm was the holder of certain obligations at the time of your father's death. You have been gone very long without word to us. Meantime, pending any action—"

"You have moved in!"

"I have ventured to take possession, Mr. Cowles. That was as your mother wished. She waived all her rights and surrendered everything, said all the debts must be paid—"

"Of course—"

"And all we could prevail upon her to do was to take up her quarters there in one of the little houses."

He pointed with this euphemism toward our old servants' quarters. So there was my mother, a woman gently reared, tenderly cared for all her life, living in a cabin where once slaves had lived. And I had come back to her, to tell a story such as mine!

"I hope," said he, hesitating, "that all these matters may presently be adjusted. But first I ask you to influence your mother to come back into the place and take up her residence."

I smiled slowly. "You hardly understand her," I said. "I doubt if my influence will suffice for that. But I shall meet you again." I was turning away.

"Your mother, I believe, is not here—she went over to Wallingford. I think it is the day when she goes to the little church—"

"Yes, I know. If you will excuse me I shall ride over to see if I can find her." He bowed. Presently I was hurrying down the road again. It seemed to me that I could never tolerate the sight of a stranger as master at Cowles' Farms.

I Found her at the churchyard of the old meetinghouse. She was just turning toward the gate in the low sandstone wall which surrounded the burying ground and separated it from the space immediately about the little stone church. It was a beautiful spot, here where the sun came through the great oaks that had never known an ax, resting upon blue grass that had never known a plow—a spot virgin as it was before old Lord Fairfax ever claimed it hi his loose ownership. Everything about it spoke of quiet and gentleness.

I knew what it was that she looked upon as she turned back toward that spot—it was one more low mound, simple, unpretentious, added to the many which had been placed there this last century and a half; one more little gray sandstone head-mark, cut simply with the name and dates of him who rested there, last in a long roll of our others. The slight figure in the dove-colored gown looked back lingeringly. It gave a new ache to my heart to see her there.

She did not notice me as I slipped down from my saddle and fastened my horse at the long rack. But when I called she turned and came to me with open arms.

"Jack!" she cried. "My son, how I have missed thee! Now thee has come back to thy mother." She put her forehead on my shoulder, but presently took up a mother's scrutiny. Her hand stroked my hair, my unshaven beard, took in each line of my face.

"Thee has a button from thy coat," she said, reprovingly. "And what is this scar on thy neck—thee did not tell me when thee wrote, Jack, what ails thee?" She looked at me closely. "Thee is changed. Thee is older—what has come to thee, my son?"

"Come," I said to her at length, and led her toward the steps of the little church.

Then I broke out bitterly and railed against our ill-fortune, and cursed at the man who would allow her to live in servants' quarters—indeed, railed at all of life.

"Thee must learn to subdue thyself, my son," she said. "It is only so that strength comes to us—when we bend the back to the furrow God sets for us. I am quite content in my little rooms. I have made them very clean; and I have with me a few things of my own—a few, not many."

"But your neighbors, mother, the Sheratons—"

"Oh, certainly, they asked me to live with them. But I was not moved to do that. You see, I know each rose bush and each apple tree on our old place. I did not like to leave them.

"Besides, as to the Sheratons, Jack," she began again—"I do not wish to say one word to hurt thy feelings, but Miss Grace—"

"What about Miss Grace?"

"Mr. Orme, the gentleman who once stopped with us a few days—"

"Oh, Orme! Is he here again? He was all through the West with me—I met him everywhere there. Now I meet him here!"

"He returned last summer, and for most of his time has been living at the Sheratons'. He and Colonel Sheraton agree very well. And he and Miss Grace—I do not like to say these things to thee, my son, but they also seem to agree."

"Go on," I demanded, bitterly.

"Whether Miss Grace's fancy has changed, I do not know, but thy mother ought to tell thee this, so that if she should jilt thee, why, then—"

"Yes," said I, slowly, "it would be hard for me to speak the first word as to a release."

"But if she does not love thee, surely she will speak that word. So then say good-by to her and set about thy business."

I could not at that moment find it in my heart to speak further. We rose and walked down to the street of the little town, and at the tavern barn I secured a conveyance which took us both back to what had once been our home. It was my mother's hands which, at a blackened old fireplace, in a former slave's cabin, prepared what we ate that evening. Then, as the sun sank in a warm glow beyond the old Blue Ridge, and our little valley lay there warm and peaceful as of old, I drew her to the rude porch of the whitewashed cabin, and we looked out, and talked of things which must be mentioned. I told her—told her all my sad and bitter story, from end to end.

"This, then," I concluded, more than an hour after I had begun, "is what I have brought back to you—failure,

Comments (0)