The Silent Isle, Arthur Christopher Benson [best book reader txt] 📗

- Author: Arthur Christopher Benson

Book online «The Silent Isle, Arthur Christopher Benson [best book reader txt] 📗». Author Arthur Christopher Benson

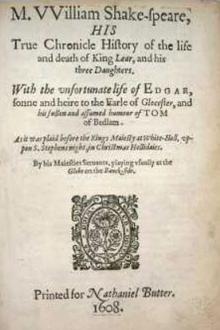

Shakespeare they are shadowy and broken; in Wordsworth they relentlessly improve the occasion. What one desires to see depicted is some figure that has gained in gentleness and tolerance without losing, shrewdness and perception; who is as much interested as ever in seeing the game played, without being enviously desirous to take a hand. The thing is so perfectly beautiful when it occurs in real life that it is hard to see why it should not be represented.

XLV

I seem to remember having lately seen at the Zoo a strange and melancholy fowl, of a tortoise-shell complexion, glaring sullenly from a cage, with that curious look of age and toothlessness that eagles have, from the overlapping of the upper mandible of the beak above the lower; it was labelled the Monkey-eating Eagle. Its food lay untasted on the floor; it much preferred, no doubt, and from no fault of its own, poor thing, a nice, plump, squalling baboon to the finest of chops without the fun!

But the name set me thinking, and brought to mind a very different kind of creature, from whom I have suffered much of late, the Eagle-eating Monkey by which I mean the writer of bad books about great people. I had personally always supposed that I would rather read even a poor book about a real human being than the cleverest of books about imaginary people; at least I thought so till I was obliged to read a large number of memoirs and biographies, written some by stupid painstaking people, and some by clever aggravating people, about a number of celebrated persons.

The stupid book is tiresome enough, because it ends by making one feel that there is a real human being whom one cannot get at behind all the tedious paragraphs, like some one stirring and coughing behind a screen--or even more like the outline of a human figure covered up with a quilt, so that one can just infer which is the head and which the feet, but with the outlines all overlaid with a woolly padded texture of meaningless words. Such biographers as these are hardly eagle-eating monkeys. They are rather monkeys who would eat a live eagle if they could catch one, and will mangle a dead one if they can find him. The marvel is that with material at their command, with friends of their victim to interrogate, and sometimes even with a personal knowledge of him, they can yet contrive to avoid telling one anything interesting or characteristic. The only points which seem to strike them are the points in which their hero resembled other people, not the points in which he differed from others. They tell you that they remember an interesting conversation with the great man, and go on to say that no words could do justice to the charm of his talk. Or they will tell you his views on Free Trade or the Poor Law, and quote long extracts from his speeches and public utterances. But they never admit one behind the scenes, either because they were never there themselves, or did not know it when they were. Or, worse still, they will say that they do not think it decorous to violate the privacy of his domestic circle, with the result that there comes out a figure like the statue of a statesman in a public garden, in bronze frock-coat and trousers, with a roll of paper in his hand, addressing the world in general, with the rain dripping from his nose and his coat-tails.

That is a very bad kind of biography; and the worst of it is that it is often the result of a pompous consciousness of virtue and fidelity, which argues that because a man disliked personal paragraphs about his favourite dishes and his private amusements, when he was alive, he would therefore resent a picture of his real life being drawn when he was dead; and this inconvenient decorum arises from a deep-seated poverty of imagination, which regards death as converting all alike into a species of angels, and which can only conceive of heaven as a sort of cathedral, with the spirits of eminent men employed as canons in perpetual residence. Thus it is bad biography because it is false biography, emphasising virtues and omitting faults, and, what is almost worse, omitting characteristic traits.

But it is not the worst kind of biography. The joy of the real eagle-eating biographer is to do what Tennyson bluntly described as ripping up people like pigs, and violating not privacy but decency; sweeping together odious little anecdotes, recording meannesses and weaknesses and sillinesses, all the things of which the subject himself was no doubt heartily ashamed and discarded as eagerly as possible. Such biographies give one the sense of a man diving in sewers, grubbing in middens, prying into cupboards, peeping round corners. To try as far as possible to surprise your hero, and to catch him off his guard, is a very different thing from being frank and candid. I remember once coming upon the track of one of these ghouls. He was writing a Life of a somewhat eccentric politician, and wrote to me asking me to obtain for him a sight of a certain document. I forwarded his letter to the relatives of the man in question. What was my surprise when they replied that the biographer was not only wholly unauthorised by themselves, but that they had written to him to remonstrate against his expressed intention, and to beg him to desist. I forwarded the letter to him, and added some comments of my own. The only result was that he replied regretting the opposition of the relatives, saying that the life of a public man was public property, and that he thought it his duty to continue his researches. The book appeared, and a vile rag-bag it was, like the life of a man written by a private detective from the reminiscences of under-servants. The worst of it is that such a compilation brings a man money, because there are always plenty of people who like to dabble in mud; and a ghoul is the most impervious of beings, probably because a ghoul of this species regards himself merely as an unprejudiced seeker after truth, and claims to be what he would call a realist.

The reason why such realism is bad art is not because the details are untrue, but because the proportion is wrong. One cannot tell everything in a biography, unless one is prepared to write on the scale of a volume for each week of the hero's life. The art of the biographer is to select what is salient and typical, not what is abnormal and negligible; what he should aim at is to suggest, by skilful touches, a living portrait. If the subject is bald and wrinkled, he must be painted so. But there is no excuse for trying to depict his hero's toe-nails, unless there is a very valid reason for doing so. And there is still less excuse for painting them so big that one can see little else in the picture! Ex ungue leonem, says the proverb; but it is a scientific and not an artistic maxim.

One sometimes wonders what will be the future of biographies; how, as libraries get fuller and records increase, it will be possible ever to write the lives of any but men of prime importance. I suppose the difficulty will solve itself in some perfectly simple and obvious manner; but the obstacle is that, as reading gets more common, the circle of trivial people who are interested in trousers and toe-nails and in little else does undoubtedly increase. Moreover, instead of fewer biographies being written, more and more people seem to be commemorated in stodgy volumes; and further, the selection could not be made by authority, because the kind of lives that are wanted are not the lives of dull important people, but the lives of interesting and unimportant people who have given their vividness and originality to life itself, to talk and letters and complex relationships; we do not want the lives of people who have prosed on platforms and bawled at the openings of bazaars. They have said their say, and we have heard as much as we need to hear of their views already. But I know half-a-dozen people, of whose words and works probably no record whatever will be made, whose lives, if they could be painted, would be more interesting than any novel, and more inspiring than any sermon; who have not taken things for granted, but have made up their own minds; and, what is more, have really had minds to make up; who have said, day after day, fine, humorous, tender, illuminating things; who have loved life better than routine, and ideas-better than success; who have really enriched the blood of the world, instead of feebly adulterating it; who have given their companions zest and joy, trenchant memories and eager emotions: but the whole process has been so delicate, so evasive, so informal, that it seems impossible to recapture the charm in heavy words. A man who would set himself to write the life of one of these delightful people, instead of adding to the interminable stream of tiresome romances which inundate us, might leave a very fine legacy to the world. It would mean an immense amount of trouble, and the cultivation of a Boswellian memory--for such a book would consist largely of recorded conversations--but what a hopeful and uplifting thing it would be to read and re-read!

The difficulty is that to a perceptive man--and none but a man of the finest perception could do it,--an eagle-eating eagle, in fact--it would seem a ghoulish and a treacherous business. He would feel like an interviewer and like a spy. It would have to be done in a noble, self-denying sort of secrecy, amassing and recording day by day; and he would never be able to let his hero suspect what was happening, or the gracious spontaneity would vanish; for the essence of such a life and such talk as I have described is that they should be wholly frank and unconsidered; and the thought of the presence of the note-taking spectator would overshadow its radiance at once.

There is a task for a patient, unambitious, perceptive man! He must be a man of infinite leisure, and he must be ready to take a large risk of disappointment; for he must outlive his subject, and he must be willing to sacrifice all other opportunities of artistic creation. But he might write one of the great books of the world, and win a secure seat upon the Muses' Hill.

XLVI

I have been reading all the old Shelley literature lately, Hogg and Trelawny and Medwin and Mrs. Shelley, and that terrible piece of analysis, The Real Shelley. Hogg's Life of Shelley is an incomparable book; I should put it in the first class of biographies without hesitation. Of course, it is only a fragment; and much of it is frankly devoted to the sayings and doings of Hogg; it is none the worse for that. It is an intensely humorous book, in the first place. There are marvellous episodes in it, splendid extravaganzas like the story of Hogg's stay in Dublin, where he locked the door of his bedroom for security, and the boy Pat crept through the panel of the door to get his boots and keep them from him, and a man in the room below pushed up a plank in the floor that he might converse, not with Hogg, but with the man in the room above him; there is the anecdote of the little banker who was convinced that Wordsworth was a poet because he had trained himself to write in the dark if

XLV

I seem to remember having lately seen at the Zoo a strange and melancholy fowl, of a tortoise-shell complexion, glaring sullenly from a cage, with that curious look of age and toothlessness that eagles have, from the overlapping of the upper mandible of the beak above the lower; it was labelled the Monkey-eating Eagle. Its food lay untasted on the floor; it much preferred, no doubt, and from no fault of its own, poor thing, a nice, plump, squalling baboon to the finest of chops without the fun!

But the name set me thinking, and brought to mind a very different kind of creature, from whom I have suffered much of late, the Eagle-eating Monkey by which I mean the writer of bad books about great people. I had personally always supposed that I would rather read even a poor book about a real human being than the cleverest of books about imaginary people; at least I thought so till I was obliged to read a large number of memoirs and biographies, written some by stupid painstaking people, and some by clever aggravating people, about a number of celebrated persons.

The stupid book is tiresome enough, because it ends by making one feel that there is a real human being whom one cannot get at behind all the tedious paragraphs, like some one stirring and coughing behind a screen--or even more like the outline of a human figure covered up with a quilt, so that one can just infer which is the head and which the feet, but with the outlines all overlaid with a woolly padded texture of meaningless words. Such biographers as these are hardly eagle-eating monkeys. They are rather monkeys who would eat a live eagle if they could catch one, and will mangle a dead one if they can find him. The marvel is that with material at their command, with friends of their victim to interrogate, and sometimes even with a personal knowledge of him, they can yet contrive to avoid telling one anything interesting or characteristic. The only points which seem to strike them are the points in which their hero resembled other people, not the points in which he differed from others. They tell you that they remember an interesting conversation with the great man, and go on to say that no words could do justice to the charm of his talk. Or they will tell you his views on Free Trade or the Poor Law, and quote long extracts from his speeches and public utterances. But they never admit one behind the scenes, either because they were never there themselves, or did not know it when they were. Or, worse still, they will say that they do not think it decorous to violate the privacy of his domestic circle, with the result that there comes out a figure like the statue of a statesman in a public garden, in bronze frock-coat and trousers, with a roll of paper in his hand, addressing the world in general, with the rain dripping from his nose and his coat-tails.

That is a very bad kind of biography; and the worst of it is that it is often the result of a pompous consciousness of virtue and fidelity, which argues that because a man disliked personal paragraphs about his favourite dishes and his private amusements, when he was alive, he would therefore resent a picture of his real life being drawn when he was dead; and this inconvenient decorum arises from a deep-seated poverty of imagination, which regards death as converting all alike into a species of angels, and which can only conceive of heaven as a sort of cathedral, with the spirits of eminent men employed as canons in perpetual residence. Thus it is bad biography because it is false biography, emphasising virtues and omitting faults, and, what is almost worse, omitting characteristic traits.

But it is not the worst kind of biography. The joy of the real eagle-eating biographer is to do what Tennyson bluntly described as ripping up people like pigs, and violating not privacy but decency; sweeping together odious little anecdotes, recording meannesses and weaknesses and sillinesses, all the things of which the subject himself was no doubt heartily ashamed and discarded as eagerly as possible. Such biographies give one the sense of a man diving in sewers, grubbing in middens, prying into cupboards, peeping round corners. To try as far as possible to surprise your hero, and to catch him off his guard, is a very different thing from being frank and candid. I remember once coming upon the track of one of these ghouls. He was writing a Life of a somewhat eccentric politician, and wrote to me asking me to obtain for him a sight of a certain document. I forwarded his letter to the relatives of the man in question. What was my surprise when they replied that the biographer was not only wholly unauthorised by themselves, but that they had written to him to remonstrate against his expressed intention, and to beg him to desist. I forwarded the letter to him, and added some comments of my own. The only result was that he replied regretting the opposition of the relatives, saying that the life of a public man was public property, and that he thought it his duty to continue his researches. The book appeared, and a vile rag-bag it was, like the life of a man written by a private detective from the reminiscences of under-servants. The worst of it is that such a compilation brings a man money, because there are always plenty of people who like to dabble in mud; and a ghoul is the most impervious of beings, probably because a ghoul of this species regards himself merely as an unprejudiced seeker after truth, and claims to be what he would call a realist.

The reason why such realism is bad art is not because the details are untrue, but because the proportion is wrong. One cannot tell everything in a biography, unless one is prepared to write on the scale of a volume for each week of the hero's life. The art of the biographer is to select what is salient and typical, not what is abnormal and negligible; what he should aim at is to suggest, by skilful touches, a living portrait. If the subject is bald and wrinkled, he must be painted so. But there is no excuse for trying to depict his hero's toe-nails, unless there is a very valid reason for doing so. And there is still less excuse for painting them so big that one can see little else in the picture! Ex ungue leonem, says the proverb; but it is a scientific and not an artistic maxim.

One sometimes wonders what will be the future of biographies; how, as libraries get fuller and records increase, it will be possible ever to write the lives of any but men of prime importance. I suppose the difficulty will solve itself in some perfectly simple and obvious manner; but the obstacle is that, as reading gets more common, the circle of trivial people who are interested in trousers and toe-nails and in little else does undoubtedly increase. Moreover, instead of fewer biographies being written, more and more people seem to be commemorated in stodgy volumes; and further, the selection could not be made by authority, because the kind of lives that are wanted are not the lives of dull important people, but the lives of interesting and unimportant people who have given their vividness and originality to life itself, to talk and letters and complex relationships; we do not want the lives of people who have prosed on platforms and bawled at the openings of bazaars. They have said their say, and we have heard as much as we need to hear of their views already. But I know half-a-dozen people, of whose words and works probably no record whatever will be made, whose lives, if they could be painted, would be more interesting than any novel, and more inspiring than any sermon; who have not taken things for granted, but have made up their own minds; and, what is more, have really had minds to make up; who have said, day after day, fine, humorous, tender, illuminating things; who have loved life better than routine, and ideas-better than success; who have really enriched the blood of the world, instead of feebly adulterating it; who have given their companions zest and joy, trenchant memories and eager emotions: but the whole process has been so delicate, so evasive, so informal, that it seems impossible to recapture the charm in heavy words. A man who would set himself to write the life of one of these delightful people, instead of adding to the interminable stream of tiresome romances which inundate us, might leave a very fine legacy to the world. It would mean an immense amount of trouble, and the cultivation of a Boswellian memory--for such a book would consist largely of recorded conversations--but what a hopeful and uplifting thing it would be to read and re-read!

The difficulty is that to a perceptive man--and none but a man of the finest perception could do it,--an eagle-eating eagle, in fact--it would seem a ghoulish and a treacherous business. He would feel like an interviewer and like a spy. It would have to be done in a noble, self-denying sort of secrecy, amassing and recording day by day; and he would never be able to let his hero suspect what was happening, or the gracious spontaneity would vanish; for the essence of such a life and such talk as I have described is that they should be wholly frank and unconsidered; and the thought of the presence of the note-taking spectator would overshadow its radiance at once.

There is a task for a patient, unambitious, perceptive man! He must be a man of infinite leisure, and he must be ready to take a large risk of disappointment; for he must outlive his subject, and he must be willing to sacrifice all other opportunities of artistic creation. But he might write one of the great books of the world, and win a secure seat upon the Muses' Hill.

XLVI

I have been reading all the old Shelley literature lately, Hogg and Trelawny and Medwin and Mrs. Shelley, and that terrible piece of analysis, The Real Shelley. Hogg's Life of Shelley is an incomparable book; I should put it in the first class of biographies without hesitation. Of course, it is only a fragment; and much of it is frankly devoted to the sayings and doings of Hogg; it is none the worse for that. It is an intensely humorous book, in the first place. There are marvellous episodes in it, splendid extravaganzas like the story of Hogg's stay in Dublin, where he locked the door of his bedroom for security, and the boy Pat crept through the panel of the door to get his boots and keep them from him, and a man in the room below pushed up a plank in the floor that he might converse, not with Hogg, but with the man in the room above him; there is the anecdote of the little banker who was convinced that Wordsworth was a poet because he had trained himself to write in the dark if

Free e-book «The Silent Isle, Arthur Christopher Benson [best book reader txt] 📗» - read online now

Similar e-books:

Comments (0)