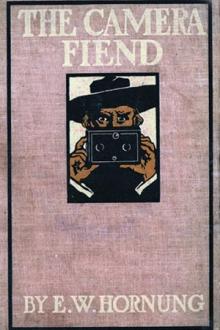

The Camera Fiend, E. W. Hornung [important of reading books txt] 📗

- Author: E. W. Hornung

- Performer: -

Book online «The Camera Fiend, E. W. Hornung [important of reading books txt] 📗». Author E. W. Hornung

“It was then,” he wrote, “that I formed a [pg 307] project which I should have been sorry indeed to carry out, though I should certainly have done so if he had given me the chance I sought. It must be understood that my second attempt to photograph the flight of the soul had proved as great a fiasco as the first. Suddenly I hit upon a perfectly conceivable (even though it seem a wilfully grotesque) explanation of my failure. What if the human derelicts I had so far chosen for my experiments had no souls to photograph? Sodden with drink, debauched, degraded, and spiritually blurred or blunted to the last degree, these after all were the least likely subjects to yield results to the spirit photographer. I should have chosen saints instead of sinners such as these, entities in which the soul was a major and not a minor factor. I thought of the saintliest men I knew in London, of some Jesuit Fathers of my acquaintance, of a ‘light’ specialist I know of who is destroying himself by inches in the cause of science, of certain missioners in the slums; but I did not think twice of any one of them; their lives are much too valuable for me to cut them short on the mere chance of a compensating benefit to mankind at large. Last, and longest, I thought of the boy upstairs. I had not meant to sacrifice him; a young life, of some promise, is only less sacred to me than a mature life rich in beneficent activities. But this young [pg 308] fellow was going to be my ruin. I could see it in his eyes. He had found me out about the letter; he would be the means of my being found out and stopped for ever in the work of my life. It was his life or mine; it should be his; but I was not going to take it there in the house, for reasons I need not enter into here, and I intended to take more than his life while I was about it. But he never gave me the chance. I did my best to get him to go out with me this morning. But he refused, as a horse refuses a jump, or a dog the water. He said he was ill; he looked ill. But I have no doubt he was well enough to make his escape soon after my back was turned. I see he has broken into my dark-room for the clothes I took away from him before I went out; he would scarcely remain after that; but, to tell the truth, I have hardly given him a thought since my return.”

The readers shuddered over this long paragraph. More than once the boy broke in with his own impulsive version of the awful moments on the Sunday night and the Monday morning, in his bedroom at the top of the doctor's house. He declared that nothing short of main force would have dragged him out-of-doors that morning, that he felt it in his bones that he would never come back alive. Then he would be sorry he had said so much.

[pg 309]It only increased his companion's anguish. She was reading every word religiously, with a most painful fascination; it was as though every word drew blood. There was a brief but terrible account of the murder of Sir Joseph Schelmerdine outside his own house in Park Lane. It was the rashest of all the crimes; but, apparently, the one occasion on which the doctor had disguised himself before hand; and that only because Sir Joseph and he knew and disliked each other so intensely that a “straight” interview was out of the question. As it was he had escaped by a miracle, after lying all day in a straw-loft, creeping into a carriage at nightfall, and getting out on the wrong side when it drove round to its house. Baumgartner described the incident with a callous relish, as perhaps the most exciting in his long career; he was going on to explain his subsequent return, in propria persona, and yet by stealth, when he paused in the middle of a sentence which was never finished. And his statement concluded as follows, in less careful language and a more flowing hand:—

“I thought the fool had cleared out long ago. The day's excitement must have driven him clean out of my head. I never thought of him when I got back, never till I saw the damage to the darkroom window and missed his clothes. I didn't [pg 310] waste two thoughts upon him then. I had my negative to develop. A magnificent negative it was, too, yet another absolute failure from the practical point of view, perhaps from the same reason as its predecessors. South African mines may produce gold and diamonds (licit and illicit!) but their yield in souls is probably the poorest to the square mile anywhere on earth. Schelmerdine never had one in his gross carcass. So there was an end of him, and a good riddance to rotten clay. I have not thought of him again all night. I have thought of nothing but this perhaps passionately dispassionate statement that I have made up my mind to leave behind me. It has given me strange pleasure to write, a satisfaction which I have no longer the time to attempt to analyse; all night long my pen has scarcely paused, and I not conscious of a moment's weariness of mind, body, or hand. Only sometimes have I paused to light my pipe. I had made such a pause, perhaps half an hour ago, when in the terrible stillness of the night I heard a footstep in the hall. My nerves were somewhat on edge with all this writing; it might be my imagination. I stole to my door, and as I opened it the one below shut softly. I waited some time, heard nothing more, went down with my lamp, and threw open the drawing-room door. There was my young fellow, not gone at all, but [pg 311] sitting in the dark with one whose name there is no need to mention. I do not wish to be misunderstood. It was all innocent enough, even I never doubted that. But somehow the sight of that boy and girl, sitting there in the dark without a word, afraid to go to bed—afraid of me—made the blood boil over in my veins. I could have trampled on that lad, my Jonah whom I had pictured overboard at last, and I did hurl the lamp at his head. I am glad it missed him. I am glad he made good his escape while I was seeing his companion safe upstairs. If I had found him where I left him, God knows what violence I might not have done him after all. The boy has good in him, and more courage than he knows himself; again I say that I am glad he has escaped unscathed. His life was not safe, but now I shall only take my own.”

“Yes! I have made up my mind; it is better than leaving it to the common hangman of this besotted country. I know what to expect in enlightened England: either a death unfit for a dog, or existence worse than death in a criminal lunatic asylum. I prefer my own peculiar quietus; it has stood on my table all night long, ready and pointed at my heart; a hand upon the door, a step behind me, and I should have rolled over dead at their feet. So it will be if even now they are waiting for me outside; but, if not, I know where to go, [pg 312] where already it is broad daylight, where the wide open space will quicken and enhance every ray, and the broad river multiply the sun by a million facets of living fire. It is not the light that will fail me, there; and as I have served others, so also will I serve myself, and it may be with better fortune than they have brought me. Who knows? It would be in keeping with the poetic ironies of this existence. At all events, unless waylaid at once, I am giving it a chance. I shall place the camera on the parapet of the Embankment. I have fitted the shutter with a specially long pneumatic tube, and the bulb will do its double work as usual when my fingers relax. I have long had it all in my mind. I have written full instructions on the envelope which I shall stick by the flap to the open slide; if we are found by a reasonably intelligent person, the slide will be shut, and the camera handed over bodily to the police. They, I think, may be trusted to honour one's last instructions, if only out of curiosity; their eyes will be the first to read what I fear they will describe as my ‘full confession.’ Well, it is ‘full,’ and the substantive must be left to them. So long as the document does not fall into one little pair of gentle hands, I shall lie easy in whatever ignominious grave they lay me. That is why I hide it where I do: since, if it fell first into those hands, it would never see the light at all.”

[pg 313]There was a little more, but Phillida suddenly snatched the MS. away, and wept over the end, bitterly, and yet not altogether in bitterness, while Pocket picked up the camera and set it back in its place on the muddy newspaper. Phillida folded up the packet, and after a moment's hesitation went away with it, jingling keys in her other hand. On her return she stood petrified on the threshold.

Pocket was seated at the table, the red bulb of the pneumatic shutter between his finger and thumb; he pressed the bulb, and there was a loud metallic snap inside the camera; he released the pressure, and the shutter snapped like a shutter and nothing else. Phillida came forward with a cry. Pocket had taken the top off the camera; it was like a box without the lid, and on the one side there was nothing between the lens and the grooved carrier for the slide, but on the other there was an automatic pistol, fixed down with wires, as a wild beast might be lashed, and its muzzle pointing through the orifice intended for the second lens of the stereoscopic camera.

Pocket pressed again, and again the mild clash of the shutter was preceded by the vicious one that would have been an explosion if there had been another cartridge in the pistol.

Comments (0)