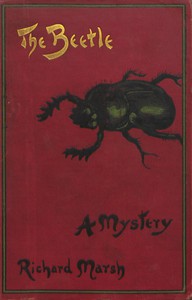

The Beetle: A Mystery, Richard Marsh [chromebook ebook reader .TXT] 📗

- Author: Richard Marsh

Book online «The Beetle: A Mystery, Richard Marsh [chromebook ebook reader .TXT] 📗». Author Richard Marsh

Sydney held something in front of him. Mr Lessingham wriggled to one side to enable him to see. Then he made a snatch at it.

‘It’s mine!’

Sydney dodged it out of his reach.

‘What do you mean, it’s yours?’

‘It’s the ring I gave Marjorie for an engagement ring. Give it me, you hound!—unless you wish me to do you violence in the cab.’

With complete disregard of the limitations of space,—or of my comfort,—Lessingham thrust him vigorously aside. Then gripping Sydney by the wrist, he seized the gaud,—Sydney yielding it just in time to save himself from being precipitated into the street. Ravished of his treasure, Sydney turned and surveyed the ravisher with something like a glance of admiration.

‘Hang me, Lessingham, if I don’t believe there is some warm blood in those fishlike veins of yours. Please the piper, I’ll live to fight you after all,—with the bare ones, sir, as a gentleman should do.’

Lessingham seemed to pay no attention to him whatever. He was surveying the ring, which Sydney had trampled out of shape, with looks of the deepest concern.

‘Marjorie’s ring!—The one I gave her! Something serious must have happened to her before she would have dropped my ring, and left it lying where it fell.’

Atherton went on.

‘That’s it!—What has happened to her!—I’ll be dashed if I know!—When it was clear that there she wasn’t, I tore off to find out where she was. Came across old Lindon,—he knew nothing;—I rather fancy I startled him in the middle of Pall Mall, when I left he stared after me like one possessed, and his hat was lying in the gutter. Went home,—she wasn’t there. Asked Dora Grayling,—she’d seen nothing of her. No one had seen anything of her,—she had vanished into air. Then I said to myself, “You’re a first-class idiot, on my honour! While you’re looking for her, like a lost sheep, the betting is that the girl’s in Holt’s friend’s house the whole jolly time. When you were there, the chances are that she’d just stepped out for a stroll, and that now she’s back again, and wondering where on earth you’ve gone!” So I made up my mind that I’d fly back and see,—because the idea of her standing on the front doorstep looking for me, while I was going off my nut looking for her, commended itself to what I call my sense of humour; and on my way it struck me that it would be the part of wisdom to pick up Champnell, because if there is a man who can be backed to find a needle in any amount of haystacks it is the great Augustus.—That horse has moved itself after all, because here we are. Now, cabman, don’t go driving further on,—you’ll have to put a girdle round the earth if you do; because you’ll have to reach this point again before you get your fare.—This is the magician’s house!’

CHAPTER XXXVII.WHAT WAS HIDDEN UNDER THE FLOOR

The cab pulled up in front of a tumbledown cheap ‘villa’ in an unfinished cheap neighbourhood,—the whole place a living monument of the defeat of the speculative builder.

Atherton leaped out on to the grass-grown rubble which was meant for a footpath.

‘I don’t see Marjorie looking for me on the doorstep.’

Nor did I,—I saw nothing but what appeared to be an unoccupied ramshackle brick abomination. Suddenly Sydney gave an exclamation.

‘Hullo!—The front door’s closed!’

I was hard at his heels.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Why, when I went I left the front door open. It looks as if I’ve made an idiot of myself after all, and Marjorie’s returned,—let’s hope to goodness that I have.’

He knocked. While we waited for a response I questioned him.

‘Why did you leave the door open when you went?’

‘I hardly know,—I imagine that it was with some dim idea of Marjorie’s being able to get in if she returned while I was absent,—but the truth is I was in such a condition of helter skelter that I am not prepared to swear that I had any reasonable reason.’

‘I suppose there is no doubt that you did leave it open?’

‘Absolutely none,—on that I’ll stake my life.’

‘Was it open when you returned from your pursuit of Holt?’

‘Wide open,—I walked straight in expecting to find her waiting for me in the front room,—I was struck all of a heap when I found she wasn’t there.’

‘Were there any signs of a struggle?’

‘None,—there were no signs of anything. Everything was just as I had left it, with the exception of the ring which I trod on in the passage, and which Lessingham has.’

‘If Miss Lindon has returned, it does not look as if she were in the house at present.’

It did not,—unless silence had such meaning. Atherton had knocked loudly three times without succeeding in attracting the slightest notice from within.

‘It strikes me that this is another case of seeking admission through that hospitable window at the back.’

Atherton led the way to the rear. Lessingham and I followed. There was not even an apology for a yard, still less a garden,—there was not even a fence of any sort, to serve as an enclosure, and to shut off the house from the wilderness of waste land. The kitchen window was open. I asked Sydney if he had left it so.

‘I don’t know,—I dare say we did; I don’t fancy that either of us stood on the order of his coming.’

While he spoke, he scrambled over the sill. We followed. When he was in, he shouted at the top of his voice,

‘Marjorie! Marjorie! Speak to me, Marjorie,—it is I,—Sydney!’

The words echoed through the house. Only silence answered. He led the way to the front room. Suddenly he stopped.

‘Hollo!’ he cried. ‘The blind’s down!’ I had noticed, when we were outside, that the blind was down at the front room window. ‘It was up when I went, that I’ll swear. That someone has been here is pretty plain,—let’s hope it’s Marjorie.’

He had only taken a step forward into the room when he again stopped short to exclaim.

‘My stars!—here’s a sudden clearance!—Why, the place is empty,—everything’s clean gone!’

‘What do you mean?—was it furnished when you left?’

The room was empty enough then.

‘Furnished?—I don’t know that it was exactly what you’d call furnished,—the party who ran this establishment had a taste in upholstery which was all his own,—but there was a carpet, and a bed, and—and lots of things,—for the most part, I should have said, distinctly Eastern curiosities. They seem to have evaporated into smoke,—which may be a way which is common enough among Eastern curiosities, though it’s queer to me.’

Atherton was staring about him as if he found it difficult to credit the evidence of his own eyes.

‘How long ago is it since you left?’

He referred to his watch.

‘Something over an hour,—possibly an hour and a half; I couldn’t swear to the exact moment, but it certainly isn’t more.’

‘Did you notice any signs of packing up?’

‘Not a sign.’ Going to the window he drew up the blind,—speaking as he did so. ‘The queer thing about this business is that when we first got in this blind wouldn’t draw up a little bit, so, since it wouldn’t go up I pulled it down, roller and all, now it draws up as easily and smoothly as if it had always been the best blind that ever lived.’

Standing at Sydney’s back I saw that the cabman on his box was signalling to us with his outstretched hand. Sydney perceived him too. He threw up the sash.

‘What’s the matter with you?’

‘Excuse me, sir, but who’s the old gent?’

‘What old gent?’

‘Why the old gent peeping through the window of the room upstairs?’

The words were hardly out of the driver’s mouth when Sydney was through the door and flying up the staircase. I followed rather more soberly,—his methods were a little too flighty for me. When I reached the landing, dashing out of the front room he rushed into the one at the back,—then through a door at the side. He came out shouting.

‘What’s the idiot mean!—with his old gent! I’d old gent him if I got him!—There’s not a creature about the place!’

He returned into the front room,—I at his heels. That certainly was empty,—and not only empty, but it showed no traces of recent occupation. The dust lay thick upon the floor,—there was that mouldy, earthy smell which is so frequently found in apartments which have been long untenanted.

‘Are you sure, Atherton, that there is no one at the back?’

‘Of course I’m sure,—you can go and see for yourself if you like; do you think I’m blind? Jehu’s drunk.’ Throwing up the sash he addressed the driver. ‘What do you mean with your old gent at the window?—what window?’

‘That window, sir.’

‘Go to!—you’re dreaming, man!—there’s no one here.’

‘Begging your pardon, sir, but there was someone there not a minute ago.’

‘Imagination, cabman,—the slant of the light on the glass,—or your eyesight’s defective.’

‘Excuse me, sir, but it’s not my imagination, and my eyesight’s as good as any man’s in England,—and as for the slant of the light on the glass, there ain’t much glass for the light to slant on. I saw him peeping through that bottom broken pane on your left hand as plainly as I see you. He must be somewhere about,—he can’t have got away,—he’s at the back. Ain’t there a cupboard nor nothing where he could hide?’

The cabman’s manner was so extremely earnest that I went myself to see. There was a cupboard on the landing, but the door of that stood wide open, and that obviously was bare. The room behind was small, and, despite the splintered glass in the window frame, stuffy. Fragments of glass kept company with the dust on the floor, together with a choice collection of stones, brickbats, and other missiles,—which not improbably were the cause of their being there. In the corner stood a cupboard,—but a momentary examination showed that that was as bare as the other. The door at the side, which Sydney had left wide open, opened on to a closet, and that was empty. I glanced up,—there was no trap door which led to the roof. No practicable nook or cranny, in which a living being could lie concealed, was anywhere at hand.

I returned to Sydney’s shoulder to tell the cabman so.

‘There is no place in which anyone could hide, and there is no one in either of the rooms,—you must have been mistaken, driver.’

The man waxed wroth.

‘Don’t tell me! How could I come to think I saw something when I didn’t?’

‘One’s eyes are apt to play us tricks;—how could you see what wasn’t there?’

‘That’s what I want to know. As I drove up, before you told me to stop, I saw him looking through the window,—the one at which you are. He’d got his nose glued to the broken pane, and was staring as hard as he could stare. When I pulled up, off he started,—I saw him get up off his knees, and go to the back of the room. When the gentleman took to knocking, back he came,—to the same old spot, and flopped down on his knees. I didn’t know what caper you was up to,—you might be bum bailiffs for all I knew!—and I supposed that he wasn’t so anxious to let you in as you might be to get inside, and that was why he didn’t take no notice of your knocking, while all the while he kept a eye on what was going on. When you goes round to the back, up he gets again, and I reckoned that he was going to meet yer, and perhaps give yer a bit of his mind, and that presently I should hear a shindy, or that something would happen. But when you pulls up the blind downstairs, to my surprise back he come once more. He shoves his old nose right through the smash in the pane, and wags his old head at me like a chattering magpie. That didn’t seem to me quite the civil thing to do,—I hadn’t done no harm to him; so I gives you the office, and lets you know that he was there. But for you to say that he wasn’t there, and never had been,—blimey! that cops the biscuit. If he wasn’t there, all I can say is I ain’t here, and my ’orse ain’t here, and my cab ain’t neither,—damn it!—the house ain’t here, and nothing ain’t!’

He settled himself on his perch with an air of the most extreme ill usage,—he had been standing up to tell his tale. That the man was serious was unmistakable. As he himself suggested, what inducement could he have had to tell

Comments (0)