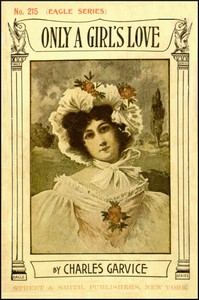

Only a Girl's Love, Charles Garvice [a book to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Garvice

Book online «Only a Girl's Love, Charles Garvice [a book to read .txt] 📗». Author Charles Garvice

The action, so full of scornful defiance, spurred Jasper back to consciousness. With a smothered oath he grasped the boy's shoulders.

Frank turned upon him with the savage ferocity of a wild[162] animal, with upraised arm. Then, suddenly, like a lightning flash, Jasper's face changed and a convulsive smile forced itself upon his lips.

He caught the arm and held it, and smiled down at him.

"My dear Frank," he murmured. "What is the matter?"

So sudden was the change, so unexpected, that Stella, who had caught the boy's other arm, stood transfixed.

Frank gasped.

"What did you mean by keeping the rose?" he burst out.

Jasper laughed softly.

"Oh, I see!" he said, nodding with amused playfulness. "I see. You were watching—from the window, perhaps, eh?" and he shook his arm playfully. "And like a great many other spectators, took jest for earnest! Impetuous boy!"

Frank looked at the pale, smiling face, and at Stella's downcast one.

"Is it true?" he asked Stella, bluntly.

"Oh, come!" said Jasper, reproachfully. "Isn't that rather rude? But I must forgive you, and I do it easily, my dear Frank, when I remember that your sudden onslaught was prompted by a desire to champion Miss Stella! Now come, you owe me a rose, go and cut me one, and we will be friends—great friends, will we not?"

Frank slid from his grasp, but stood eying him suspiciously.

"You will not?" said Jasper. "Still uncertain lest it should have been sober earnest? Then I will cut one for myself. May I?" and he smiled at Stella.

Stella did not speak, but she inclined her head.

Jasper went to one of the standards and cut a red rose deliberately and carefully, and placed it in his coat, then he cut another, and with a smile held it to Stella.

"Will that do instead of the one the stupid boy has spoiled?" he said, laughing.

Stella would have liked to refuse it, but Frank's eyes were upon her.

Slowly she held out her hand and took the rose.

A smile of triumph glittered for a moment in Jasper's eyes, then he put his hand on Frank's shoulder.

"My dear Frank," he said, in a soft voice, "you must be careful; you must repress that impulsive temper of yours, must he not?" and he turned to Stella and held out his hand. "Good-bye! It is so dangerous, you know," he murmured, holding Stella's hand, but keeping his smiling eyes fixed on the boy's face. "Why, some of these days you will be doing someone an injury and find yourself in prison, doing as they call it, six months' hard labor, like a common thief—or forger!" and he laughed, as if it were the best joke in the world.

Not so Frank. As the bantering words left the thin, smiling lips, Frank recoiled suddenly, and his face went white.

Jasper looked at him.

"And now you are sorry?" he said. "Tell me it was only your fun! Why, my dear boy, you wear your heart on your[163] sleeve! Well, if you would really like to beg my pardon, you may do it."

The boy turned his white face toward him.

"I—beg—your—pardon," he said, as if every word cost him an agony, and then, with a sudden twitch of the face, he turned and went slowly with bent head toward the house.

Jasper looked after him with a steely, cruel glitter in his eyes, and he laughed softly.

"Dear boy!" he murmured; "I have taken so fond a liking for him, and this only deepens it! He did it for your sake. You did not think I meant to keep the rose! No; I should have given it to you! But I may keep this! I will! to remind me of your promise that we may still be friends!"

And he let her hand go, and walked away.

CHAPTER XXIII.Lord Leycester was on fire as he strode up the hill to the Hall, and that notwithstanding he was wet to the skin. He was on fire with love. He swore to himself, as he climbed up the slope, that there was no one like his Stella, no one so beautiful, so lovable and sweet as the dark-eyed girl who had stolen his heart from him that moonlight night in the lane.

And he also vowed that he would wait no longer for the inestimable treasure, the exquisite happiness that lay within his grasp.

His great wealth, his time honored title seemed as nothing to him compared with the thought of possessing the first real love of his life.

He smiled rather seriously as he pictured his father's anger, his mother's dismay and despair, and Lil's, dear Lilian's, grief; but it was a smile, though a serious one.

"They will get over it when it has once been done. After all, barring that she has no title and no money—neither of which are wanted, by the way—she is as delightful a daughter-in-law as any mother or father could wish for. Yes; I'll do it!"

But how? that was the question.

"There is no Gretna Green nowadays," he pondered, regretfully. "I wish there were! A ride to the border, with my darling by my side, nestling close to me all the way with mingled love and alarm, would be worth taking. A man can't very well put up the banns in any out-of-the-way place, because there are few out-of-the-way places where they haven't heard of us Wyndwards. By Jove!" he muttered, with a little start—"there is a special license. I was almost forgetting that! That comes of not being used to being married. A special license!" and pondering deeply he reached the house.

The party at the hall was very small indeed now, but Lady Lenore and Lord Charles still remained. Lenore had once or twice declared that she must go, but Lady Wyndward had entreated her to stay.

"Do not go, Lenore," she had said, with gentle significance. "You know—you must know that we count upon you."

[164]

She did not say for what purpose she counted upon her, but Lenore had understood, and had smiled with that faint, sweet smile which constituted one of her charms.

Lord Charles stayed because Leycester was still there.

"Of course I ought to go, Lady Wyndward," he said; "you must be heartily tired of me, but who is to play billiards with Leycester if I go, or who is to keep him in order, don't you see?" and so he had stayed, with one or two others who were only too glad to remain at the Hall out of the London dust and turmoil.

By all it was quite understood that Lord Leycester should be considered as quite a free agent, free to come and go as he chose, and never to be counted on; they were as surprised as they were gratified if he joined them in a drive or a walk, and were never astonished when he disappeared without furnishing any clew to his intentions.

Lady Wyndward bore it all very patiently; she knew that what Lady Longford had said was quite true, that it was useless to attempt to drive him; but she did say a word to the old countess.

"There is something amiss!" she said, with a sigh, and the old countess had smiled and shown her teeth.

"Of course there is, my dear Ethel," she retorted; "there always is where he is concerned. He is about some mischief, I am as convinced as you are. But it does not matter, it will come all right in time."

"But will it?" asked Lady Wyndward with a sigh.

"Yes, I think so," said the old countess, "and Lenore agrees with me, or she would not stay."

"It is very good of her to stay," said Lady Wyndward, with a sigh.

"Very!" assented the old lady, with a smile. "It is encouraging. I am sure she would not stay if she did not see excuse. Yes, Ethel it will all come right; he will marry Lenore, or rather, she will marry him, and they will settle down, and—I don't know whether you have asked me to stand god-mother to the first child."

Lady Wyndward tried to feel encouraged and confident, but she felt uneasy. She was surprised that Lenore still remained. She knew nothing of that meeting between the proud beauty and Jasper Adelstone.

And Lenore! A great change had come over her. She herself could scarcely understand it.

At night—as she sat before her glass while her maid brushed out the long tresses that fell over the white shoulders like a stream of liquid gold—she asked herself what it meant? Was it really true that she was in love with Lord Leycester? She had not been in love with him when she first came to the Hall—she would have smiled away the suggestion if anyone had made it; but now—how was it with her now? And as she asked herself the question, a crimson flush would stain the beautiful face, and the violet eyes would gleam with mingled[165] shame and self-scorn, so that the maid would eye her wonderingly under respectfully lowered lids.

Yes, she was forced to admit that she did love him—love him with a passion which was a torture rather than a joy. She had not known the full extent of that passion until the hour when she had stood concealed between the trees at the river, and heard Leycester's voice murmuring words of love to another.

And that other! An unknown, miserable, painter's niece! Often, at night, when the great Hall was hushed and still, she lay tossing to and fro with miserable longing and intolerable shame, as she recalled that hour when she had been discovered by Jasper Adelstone and forced to become his confederate.

She, the great beauty—before whom princes had bent in homage—to be love-smitten by a man whose heart was given to another—she to be the confederate and accomplice of a scheming, under-bred lawyer.

It was intolerable, unbearable, but it was true—it was true; and in the very keenest paroxysm of her shame she would confess that she would do all that she had done, would conspire with even a baser one than Jasper Adelstone to gain her end.

"She!" she would murmur in the still watches of the night—"she to marry the man to whom I have given my love! It is impossible—it shall not be! Though I have to move heaven and earth, it shall not be."

And then, after a sleepless night, she would come down to breakfast—fair, and sweet, and smiling—a little pale, perhaps, but looking all the lovelier for such paleness, without the shadow of a care in the deep violet eyes.

Toward Leycester her bearing was simply perfection. She did not wish to alarm him; she knew that a hint of what she felt would put him on his guard, and she held herself in severe restraint.

Her manner to him was simply what it was to anyone else—exquisitely refined and charming. If anything, she adopted a lighter tone, and sought to and succeeded in calling forth his rare laughter.

She deceived him completely.

"Lenore in love with me!" he said to himself more than once; "the idea is ridiculous! What could have made the mother imagine such a thing?"

And so they met freely and frankly, and he talked and laughed with her at his ease, little dreaming that she was watching him as a cat watches a mouse, and that not a thing he said or did escaped her.

She knew by instinct where he spent the times in which he was missing from the Hall, and pictured to herself the meetings between him and the girl who had robbed her of his love. And as the jealousy increased, so did the love which created it. Day by day she realized still more fully that he had won her heart—that it was gone to him forever—that her whole future happiness depended upon him.

The very tone of his voice, so deep and musical—his rare[166] laugh—the smile that made his face so gay and bright—yes, even the bursts of the passionate temper which lit up the dark eyes with sudden fire, were precious to her.

"Yes, I love him," she murmured to herself—"it is all summed up in that. I love him."

And Leycester, still smiling to himself over his mother's "amusing mistake," was all unsuspecting. All his thoughts were of Stella.

Now as he came toward the terrace, she stood with Lady Longford and Lord Charles looking down at him.

She watched him, her cheek resting on her white hand, her face hidden from the rest by the sunshade, whose lining of hearty blue harmonized with the golden hair, and "her heart hungered," as Victor Hugo says.

"Here's Leycester," said Lord Charles.

Lady Longford looked over the balustrade.

"What has he been doing? Rowing—fishing?"

"He went out with a fishing rod," said Lord Charles, with a grin, "but the fish appear to have devoured it; at any rate Leycester hasn't got it now. Hullo, old man, where

Comments (0)