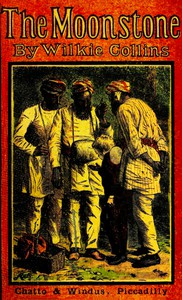

The Moonstone, Wilkie Collins [howl and other poems TXT] 📗

- Author: Wilkie Collins

Book online «The Moonstone, Wilkie Collins [howl and other poems TXT] 📗». Author Wilkie Collins

To return, however, to the history of the passing day. On finding myself alone in my room, I naturally turned my attention to the parcel which appeared to have so strangely intimidated the fresh-coloured young footman. Had my aunt sent me my promised legacy? and had it taken the form of cast-off clothes, or worn-out silver spoons, or unfashionable jewellery, or anything of that sort? Prepared to accept all, and to resent nothing, I opened the parcel—and what met my view? The twelve precious publications which I had scattered through the house, on the previous day; all returned to me by the doctor’s orders! Well might the youthful Samuel shrink when he brought his parcel into my room! Well might he run when he had performed his miserable errand! As to my aunt’s letter, it simply amounted, poor soul, to this—that she dare not disobey her medical man.

What was to be done now? With my training and my principles, I never had a moment’s doubt.

Once self-supported by conscience, once embarked on a career of manifest usefulness, the true Christian never yields. Neither public nor private influences produce the slightest effect on us, when we have once got our mission. Taxation may be the consequence of a mission; riots may be the consequence of a mission; wars may be the consequence of a mission: we go on with our work, irrespective of every human consideration which moves the world outside us. We are above reason; we are beyond ridicule; we see with nobody’s eyes, we hear with nobody’s ears, we feel with nobody’s hearts, but our own. Glorious, glorious privilege! And how is it earned? Ah, my friends, you may spare yourselves the useless inquiry! We are the only people who can earn it—for we are the only people who are always right.

In the case of my misguided aunt, the form which pious perseverance was next to take revealed itself to me plainly enough.

Preparation by clerical friends had failed, owing to Lady Verinder’s own reluctance. Preparation by books had failed, owing to the doctor’s infidel obstinacy. So be it! What was the next thing to try? The next thing to try was—Preparation by Little Notes. In other words, the books themselves having been sent back, select extracts from the books, copied by different hands, and all addressed as letters to my aunt, were, some to be sent by post, and some to be distributed about the house on the plan I had adopted on the previous day. As letters they would excite no suspicion; as letters they would be opened—and, once opened, might be read. Some of them I wrote myself. “Dear aunt, may I ask your attention to a few lines?” &c. “Dear aunt, I was reading last night, and I chanced on the following passage,” &c. Other letters were written for me by my valued fellow-workers, the sisterhood at the Mothers’-Small-Clothes. “Dear madam, pardon the interest taken in you by a true, though humble, friend.” “Dear madam, may a serious person surprise you by saying a few cheering words?” Using these and other similar forms of courteous appeal, we reintroduced all my precious passages under a form which not even the doctor’s watchful materialism could suspect. Before the shades of evening had closed around us, I had a dozen awakening letters for my aunt, instead of a dozen awakening books. Six I made immediate arrangements for sending through the post, and six I kept in my pocket for personal distribution in the house the next day.

Soon after two o’clock I was again on the field of pious conflict, addressing more kind inquiries to Samuel at Lady Verinder’s door.

My aunt had had a bad night. She was again in the room in which I had witnessed her Will, resting on the sofa, and trying to get a little sleep.

I said I would wait in the library, on the chance of seeing her. In the fervour of my zeal to distribute the letters, it never occurred to me to inquire about Rachel. The house was quiet, and it was past the hour at which the musical performance began. I took it for granted that she and her party of pleasure-seekers (Mr. Godfrey, alas! included) were all at the concert, and eagerly devoted myself to my good work, while time and opportunity were still at my own disposal.

My aunt’s correspondence of the morning—including the six awakening letters which I had posted overnight—was lying unopened on the library table. She had evidently not felt herself equal to dealing with a large mass of letters—and she might be daunted by the number of them, if she entered the library later in the day. I put one of my second set of six letters on the chimney-piece by itself; leaving it to attract her curiosity, by means of its solitary position, apart from the rest. A second letter I put purposely on the floor in the breakfast-room. The first servant who went in after me would conclude that my aunt had dropped it, and would be specially careful to restore it to her. The field thus sown on the basement story, I ran lightly upstairs to scatter my mercies next over the drawing-room floor.

Just as I entered the front room, I heard a double knock at the street-door—a soft, fluttering, considerate little knock. Before I could think of slipping back to the library (in which I was supposed to be waiting), the active young footman was in the hall, answering the door. It mattered little, as I thought. In my aunt’s state of health, visitors in general were not admitted. To my horror and amazement, the performer of the soft little knock proved to be an exception to general rules. Samuel’s voice below me (after apparently answering some questions which I did not hear) said, unmistakably, “Upstairs, if you please, sir.” The next moment I heard footsteps—a man’s footsteps—approaching the drawing-room floor. Who could this favoured male visitor possibly be? Almost as soon as I asked myself the question, the answer occurred to me. Who could it be but the doctor?

In the case of any other visitor, I should have allowed myself to be discovered in the drawing-room. There would have been nothing out of the common in my having got tired of the library, and having gone upstairs for a change. But my own self-respect stood in the way of my meeting the person who had insulted me by sending me back my books. I slipped into the little third room, which I have mentioned as communicating with the back drawing-room, and dropped the curtains which closed the open doorway. If I only waited there for a minute or two, the usual result in such cases would take place. That is to say, the doctor would be conducted to his patient’s room.

I waited a minute or two, and more than a minute or two. I heard the visitor walking restlessly backwards and forwards. I also heard him talking to himself. I even thought I recognised the voice. Had I made a mistake? Was it not the doctor, but somebody else? Mr. Bruff, for instance? No! an unerring instinct told me it was not Mr. Bruff. Whoever he was, he was still talking to himself. I parted the heavy curtains the least little morsel in the world, and listened.

The words I heard were, “I’ll do it today!” And the voice that spoke them was Mr. Godfrey Ablewhite’s.

My hand dropped from the curtain. But don’t suppose—oh, don’t suppose—that the dreadful embarrassment of my situation was the uppermost idea in my mind! So fervent still was the sisterly interest I felt in Mr. Godfrey, that I never stopped to ask myself why he was not at the concert. No! I thought only of the words—the startling words—which had just fallen from his lips. He would do it today. He had said, in a tone of terrible resolution, he would do it today. What, oh what, would he do? Something even more deplorably unworthy of him than what he had done already? Would he apostatise from the faith? Would he abandon us at the Mothers’-Small-Clothes? Had we seen the last of his angelic smile in the committee-room? Had we heard the last of his unrivalled eloquence at Exeter Hall? I was so wrought up by the bare idea of such awful eventualities as these in connection with such a man, that I believe I should have rushed from my place of concealment, and implored him in the name of all the Ladies’ Committees in London to explain himself—when I suddenly heard another voice in the room. It penetrated through the curtains; it was loud, it was bold, it was wanting in every female charm. The voice of Rachel Verinder.

“Why have you come up here, Godfrey?” she asked. “Why didn’t you go into the library?”

He laughed softly, and answered, “Miss Clack is in the library.”

“Clack in the library!” She instantly seated herself on the ottoman in the back drawing-room. “You are quite right, Godfrey. We had much better stop here.”

I had been in a burning fever, a moment since, and in some doubt what to do next. I became extremely cold now, and felt no doubt whatever. To show myself, after what I had heard, was impossible. To retreat—except into the fireplace—was equally out of the question. A martyrdom was before me. In justice to myself, I noiselessly arranged the curtains so that I could both see and hear. And then I met my martyrdom, with the spirit of a primitive Christian.

“Don’t sit on the ottoman,” the young lady proceeded. “Bring a chair, Godfrey. I like people to be opposite to me when I talk to them.”

He took the nearest seat. It was a low chair. He was very tall, and many sizes too large for it. I never saw his legs to such disadvantage before.

“Well?” she went on. “What did you say to them?”

“Just what you said, dear Rachel, to me.”

“That mamma was not at all well today? And that I didn’t quite like leaving her to go to the concert?”

“Those were the words. They were grieved to lose you at the concert, but they quite understood. All sent their love; and all expressed a cheering belief that Lady Verinder’s indisposition would soon pass away.”

“You don’t think it’s serious, do you, Godfrey?”

“Far from it! In a few days, I feel quite sure, all will be well again.”

“I think so, too. I was a little frightened at first, but I think so too. It was very kind to go and make my excuses for me to people who are almost strangers to you. But why not have gone with them to the concert? It seems very hard that you should miss the music too.”

“Don’t say that, Rachel! If you only knew how much happier I am—here, with you!”

He clasped his hands, and looked at her. In the position which he occupied, when he did that, he turned my way. Can words describe how I sickened when I noticed exactly the same pathetic expression on his face, which had charmed me when he was pleading for destitute millions of his fellow-creatures on the platform at Exeter Hall!

“It’s hard to get over one’s bad habits, Godfrey. But do try to get over the habit of paying compliments—do, to please me.”

“I never paid you a compliment, Rachel, in my life. Successful love may sometimes use the language of flattery, I admit. But hopeless love, dearest, always speaks the truth.”

He drew his chair close, and took her hand, when he said “hopeless love.” There was a momentary silence. He, who thrilled everybody, had doubtless thrilled her. I thought I now understood the words which had dropped from him when he was alone in the drawing-room, “I’ll do it today.” Alas! the most rigid propriety could hardly have failed to discover that he was doing it now.

“Have you forgotten what we agreed on, Godfrey, when you spoke to me in the country? We agreed that we were to be cousins, and nothing more.”

“I break the agreement,

Comments (0)