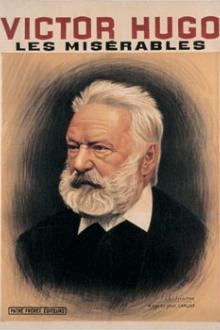

Les Misérables, Victor Hugo [best love novels of all time .TXT] 📗

- Author: Victor Hugo

- Performer: 0451525264

Book online «Les Misérables, Victor Hugo [best love novels of all time .TXT] 📗». Author Victor Hugo

They were antagonistic. He saw them in conflict. In proportion as he meditated, they grew before the eyes of his spirit. They had now attained colossal statures, and it seemed to him that he beheld within himself, in that infinity of which we were recently speaking, in the midst of the darkness and the lights, a goddess and a giant contending.

He was filled with terror; but it seemed to him that the good thought was getting the upper hand.

He felt that he was on the brink of the second decisive crisis of his conscience and of his destiny; that the Bishop had marked the first phase of his new life, and that Champmathieu marked the second. After the grand crisis, the grand test.

But the fever, allayed for an instant, gradually resumed possession of him. A thousand thoughts traversed his mind, but they continued to fortify him in his resolution.

One moment he said to himself that he was, perhaps, taking the matter too keenly; that, after all, this Champmathieu was not interesting, and that he had actually been guilty of theft.

He answered himself: “If this man has, indeed, stolen a few apples, that means a month in prison. It is a long way from that to the galleys. And who knows? Did he steal? Has it been proved? The name of Jean Valjean overwhelms him, and seems to dispense with proofs. Do not the attorneys for the Crown always proceed in this manner? He is supposed to be a thief because he is known to be a convict.”

In another instant the thought had occurred to him that, when he denounced himself, the heroism of his deed might, perhaps, be taken into consideration, and his honest life for the last seven years, and what he had done for the district, and that they would have mercy on him.

But this supposition vanished very quickly, and he smiled bitterly as he remembered that the theft of the forty sous from little Gervais put him in the position of a man guilty of a second offence after conviction, that this affair would certainly come up, and, according to the precise terms of the law, would render him liable to penal servitude for life.

He turned aside from all illusions, detached himself more and more from earth, and sought strength and consolation elsewhere. He told himself that he must do his duty; that perhaps he should not be more unhappy after doing his duty than after having avoided it; that if he allowed things to take their own course, if he remained at M. sur M., his consideration, his good name, his good works, the deference and veneration paid to him, his charity, his wealth, his popularity, his virtue, would be seasoned with a crime. And what would be the taste of all these holy things when bound up with this hideous thing? while, if he accomplished his sacrifice, a celestial idea would be mingled with the galleys, the post, the iron necklet, the green cap, unceasing toil, and pitiless shame.

At length he told himself that it must be so, that his destiny was thus allotted, that he had not authority to alter the arrangements made on high, that, in any case, he must make his choice: virtue without and abomination within, or holiness within and infamy without.

The stirring up of these lugubrious ideas did not cause his courage to fail, but his brain grow weary. He began to think of other things, of indifferent matters, in spite of himself.

The veins in his temples throbbed violently; he still paced to and fro; midnight sounded first from the parish church, then from the town-hall; he counted the twelve strokes of the two clocks, and compared the sounds of the two bells; he recalled in this connection the fact that, a few days previously, he had seen in an ironmonger’s shop an ancient clock for sale, upon which was written the name, Antoine-Albin de Romainville.

He was cold; he lighted a small fire; it did not occur to him to close the window.

In the meantime he had relapsed into his stupor; he was obliged to make a tolerably vigorous effort to recall what had been the subject of his thoughts before midnight had struck; he finally succeeded in doing this.

“Ah! yes,” he said to himself, “I had resolved to inform against myself.”

And then, all of a sudden, he thought of Fantine.

“Hold!” said he, “and what about that poor woman?”

Here a fresh crisis declared itself.

Fantine, by appearing thus abruptly in his reverie, produced the effect of an unexpected ray of light; it seemed to him as though everything about him were undergoing a change of aspect: he exclaimed:—

“Ah! but I have hitherto considered no one but myself; it is proper for me to hold my tongue or to denounce myself, to conceal my person or to save my soul, to be a despicable and respected magistrate, or an infamous and venerable convict; it is I, it is always I and nothing but I: but, good God! all this is egotism; these are diverse forms of egotism, but it is egotism all the same. What if I were to think a little about others? The highest holiness is to think of others; come, let us examine the matter. The I excepted, the I effaced, the I forgotten, what would be the result of all this? What if I denounce myself? I am arrested; this Champmathieu is released; I am put back in the galleys; that is well—and what then? What is going on here? Ah! here is a country, a town, here are factories, an industry, workers, both men and women, aged grandsires, children, poor people! All this I have created; all these I provide with their living; everywhere where there is a smoking chimney, it is I who have placed the brand on the hearth and meat in the pot; I have created ease, circulation, credit; before me there was nothing; I have elevated, vivified, informed with life, fecundated, stimulated, enriched the whole country-side; lacking me, the soul is lacking; I take myself off, everything dies: and this woman, who has suffered so much, who possesses so many merits in spite of her fall; the cause of all whose misery I have unwittingly been! And that child whom I meant to go in search of, whom I have promised to her mother; do I not also owe something to this woman, in reparation for the evil which I have done her? If I disappear, what happens? The mother dies; the child becomes what it can; that is what will take place, if I denounce myself. If I do not denounce myself? come, let us see how it will be if I do not denounce myself.”

After putting this question to himself, he paused; he seemed to undergo a momentary hesitation and trepidation; but it did not last long, and he answered himself calmly:—

“Well, this man is going to the galleys; it is true, but what the deuce! he has stolen! There is no use in my saying that he has not been guilty of theft, for he has! I remain here; I go on: in ten years I shall have made ten millions; I scatter them over the country; I have nothing of my own; what is that to me? It is not for myself that I am doing it; the prosperity of all goes on augmenting; industries are aroused and animated; factories and shops are multiplied; families, a hundred families, a thousand families, are happy; the district becomes populated; villages spring up where there were only farms before; farms rise where there was nothing; wretchedness disappears, and with wretchedness debauchery, prostitution, theft, murder; all vices disappear, all crimes: and this poor mother rears her child; and behold a whole country rich and honest! Ah! I was a fool! I was absurd! what was that I was saying about denouncing myself? I really must pay attention and not be precipitate about anything. What! because it would have pleased me to play the grand and generous; this is melodrama, after all; because I should have thought of no one but myself, the idea! for the sake of saving from a punishment, a trifle exaggerated, perhaps, but just at bottom, no one knows whom, a thief, a good-for-nothing, evidently, a whole country-side must perish! a poor woman must die in the hospital! a poor little girl must die in the street! like dogs; ah, this is abominable! And without the mother even having seen her child once more, almost without the child’s having known her mother; and all that for the sake of an old wretch of an apple-thief who, most assuredly, has deserved the galleys for something else, if not for that; fine scruples, indeed, which save a guilty man and sacrifice the innocent, which save an old vagabond who has only a few years to live at most, and who will not be more unhappy in the galleys than in his hovel, and which sacrifice a whole population, mothers, wives, children. This poor little Cosette who has no one in the world but me, and who is, no doubt, blue with cold at this moment in the den of those Thénardiers; those peoples are rascals; and I was going to neglect my duty towards all these poor creatures; and I was going off to denounce myself; and I was about to commit that unspeakable folly! Let us put it at the worst: suppose that there is a wrong action on my part in this, and that my conscience will reproach me for it some day, to accept, for the good of others, these reproaches which weigh only on myself; this evil action which compromises my soul alone; in that lies self-sacrifice; in that alone there is virtue.”

He rose and resumed his march; this time, he seemed to be content.

Diamonds are found only in the dark places of the earth; truths are found only in the depths of thought. It seemed to him, that, after having descended into these depths, after having long groped among the darkest of these shadows, he had at last found one of these diamonds, one of these truths, and that he now held it in his hand, and he was dazzled as he gazed upon it.

“Yes,” he thought, “this is right; I am on the right road; I have the solution; I must end by holding fast to something; my resolve is taken; let things take their course; let us no longer vacillate; let us no longer hang back; this is for the interest of all, not for my own; I am Madeleine, and Madeleine I remain. Woe to the man who is Jean Valjean! I am no longer he; I do not know that man; I no longer know anything; it turns out that some one is Jean Valjean at the present moment; let him look out for himself; that does not concern me; it is a fatal name which was floating abroad in the night; if it halts and descends on a head, so much the worse for that head.”

He looked into the little mirror which hung above his chimney-piece, and said:—

“Hold! it has relieved me to come to a decision; I am quite another man now.”

He proceeded a few paces further, then he stopped short.

“Come!” he said, “I must not flinch before any

Comments (0)