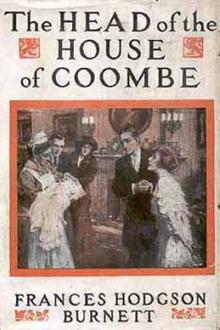

The Head of the House of Coombe, Frances Hodgson Burnett [adult books to read txt] 📗

- Author: Frances Hodgson Burnett

- Performer: -

Book online «The Head of the House of Coombe, Frances Hodgson Burnett [adult books to read txt] 📗». Author Frances Hodgson Burnett

“Dowie has told me of them,” said Mademoiselle.

“Another child might have forgotten them. I never shall. I—I was so little and they were full of something awful. It was loneliness. The first time Andrews pinched me was one day when the thing frightened me and I suddenly began to cry quite loud. I used to stare out of the window and—I don’t know when I noticed it first—I could see the children being taken out by their nurses. And there were always two or three of them and they laughed and talked and skipped. The nurses used to laugh and talk too. Andrews never did. When she took me to the gardens the other nurses sat together and chattered and their children played games with other children. Once a little girl began to talk to me and her nurse called her away. Andrews was very angry and jerked me by my arm and told me that if ever I spoke to a child again she would pinch me.”

“Devil!” exclaimed the Frenchwoman.

“I used to think and think, but I could never understand. How could I?”

“A baby!” cried Mademoiselle Valle and she got up and took her in her arms and kissed her. “Chere petite ange!” she murmured. When she sat down again her cheeks were wet. Robin’s were wet also, but she touched them with her handkerchief quickly and dried them. It was as if she had faltered for a moment in her lesson.

“Did Dowie ever tell you anything about Donal?” she asked hesitatingly.

“Something. He was the little boy you played with?”

“Yes. He was the first human creature,” she said it very slowly as if trying to find the right words to express what she meant, “—the first HUMAN creature I had ever known. You see Mademoiselle, he—he knew everything. He had always been happy, he BELONGED to people and things. I belonged to nobody and nothing. If I had been like him he would not have seemed so wonderful to me. I was in a kind of delirium of joy. If a creature who had been deaf dumb and blind had suddenly awakened, and seeing on a summer day in a world full of flowers and sun—it might have seemed to them as it seemed to me.”

“You have remembered it through all the years,” said Mademoiselle, “like that?”

“It was the first time I became alive. One could not forget it. We only played as children play but—it WAS a delirium of joy. I could not bear to go to sleep at night and forget it for a moment. Yes, I remember it—like that. There is a dream I have every now and then and it is more real than—than this is—” with a wave of her hand about her. “I am always in a real garden playing with a real Donal. And his eyes—his eyes—” she paused and thought, “There is a look in them that is like—it is just like—that first morning.”

The change which passed over her face the next moment might have been said to seem to obliterate all trace of the childish memory.

“He was taken away by his mother. That was the beginning of my finding out,” she said. “I heard Andrews talking to her sister and in a baby way I gathered that Lord Coombe had sent him. I hated Lord Coombe for years before I found out that he hadn’t—and that there was another reason. After that it took time to puzzle things out and piece them together. But at last I found out what the reason had been. Then I began to make plans. These are not my rooms,” glancing about her again, “—these are not my clothes,” with a little pull at her dress. “I’m not ‘a strong character’, Mademoiselle, as I wanted to be, but I haven’t one little regret—not one.” She kneeled down and put her arms round her old friend’s waist, lifting her face. “I’m like a leaf blown about by the wind. I don’t know what it will do with me. Where do leaves go? One never knows really.”

She put her face down on Mademoiselle’s knee then and cried with soft bitterness.

When she bade her good-bye at Charing Cross Station and stood and watched the train until it was quite out of sight, afterwards she went back to the rooms for which she felt no regrets. And before she went to bed that night Feather came and gave her farewell maternal advice and warning.

That a previously scarcely suspected daughter of Mrs. Gareth-Lawless had become a member of the household of the Dowager Duchess of Darte stirred but a passing wave of interest in a circle which was not that of Mrs. Gareth-Lawless herself and which upon the whole but casually acknowledged its curious existence as a modern abnormality. Also the attitude of the Duchess herself was composedly free from any admission of necessity for comment.

“I have no pretty young relative who can be spared to come and live with me. I am fond of things pretty and young and I am greatly pleased with what a kind chance put in my way,” she said. In her discussion of the situation with Coombe she measured it with her customary fine acumen.

“Forty years ago it could not have been done. The girl would have been made uncomfortable and outside things could not have been prevented from dragging themselves in. Filial piety in the mass would have demanded that the mother should be accounted for. Now a genial knowledge of a variety in mothers leaves Mrs. Gareth-Lawless to play about with her own probably quite amusing set. Once poor Robin would have been held responsible for her and so should I. My position would have seemed to defy serious moral issues. But we have reached a sane habit of detaching people from their relations. A nice condition we should be in if we had not.”

“You, of course, know that Henry died suddenly in some sort of fit at Ostend.” Coombe said it as if in a form of reply. She had naturally become aware of it when the rest of the world did, but had not seen him since the event.

“One did not suppose his constitution would have lasted so long,” she answered. “You are more fortunate in young Donal Muir. Have you seen him and his mother?”

“I made a special journey to Braemarnie and had a curious interview with Mrs. Muir. When I say ‘curious’ I don’t mean to imply that it was not entirely dignified. It was curious only because I realize that secretly she regards with horror and dread the fact that her boy is the prospective Head of the House of Coombe. She does not make a jest of it as I have had the temerity to do. It’s a cheap defense, this trick of making an eternal jest of things, but it IS a defense and one has formed the habit.”

“She has never done it—Helen Muir,” his friend said. “On the whole I believe she at times knows that she has been too grave. She was a beautiful creature passionately in love with her husband. When such a husband is taken away from such a woman and his child is left it often happens that the flood of her love is turned into one current and that it is almost overwhelming. She is too sane to have coddled the boy and made him effeminate—what has she done instead?”

“He is a splendid young Highlander. He would be too good-looking if he were not as strong and active as a young stag. All she has done is to so fill him with the power and sense of her charm that he has not seen enough of the world or learned to care for it. She is the one woman on earth for him and life with her at Braemarnie is all he asks for.”

“Your difficulty will be that she will not be willing to trust him to your instructions.”

“I have not as much personal vanity as I may seem to have,” Coombe said. “I put all egotism modestly aside when I talked to her and tried to explain that I would endeavour to see that he came to no harm in my society. My heir presumptive and I must see something of each other and he must become intimate with the prospect of his responsibilities. More will be demanded of the next Marquis of Coombe than has been demanded of me. And it will be DEMANDED not merely hoped for or expected. And it will be the overwhelming forces of Fate which will demand it—not mere tenants or constituents or the general public.”

“Have you any views as to WHAT will be demanded?” was her interested question.

“None. Neither has anyone else who shares my opinion. No one will have any until the readjustment comes. But before the readjustment there will be the pouring forth of blood—the blood of magnificent lads like Donal Muir—perhaps his own blood,—my God!”

“And there may be left no head of the house of Coombe,” from the Duchess.

“There will be many a house left without its head—houses great and small. And if the peril of it were more generally foreseen at this date it would be less perilous than it is.”

“Lads like that!” said the old Duchess bitterly. “Lads in their strength and joy and bloom! It is hideous.”

“In all their young virility and promise for a next generation—the strong young fathers of forever unborn millions! It’s damnable! And it will be so not only in England, but all over a blood drenched world.”

It was in this way they talked to each other of the black tragedy for which they believed the world’s stage already being set in secret, and though there were here and there others who felt the ominous inevitability of the raising of the curtain, the rest of the world looked on in careless indifference to the significance of the open training of its actors and even the resounding hammerings of its stage carpenters and builders. In these days the two discussed the matter more frequently and even in the tone of those who waited for the approach of a thing drawing nearer every day.

Each time the Head of the House of Coombe made one of his so-called “week end” visits to the parts an Englishman can reach only by crossing the Channel, he returned with new knowledge of the special direction in which the wind veered in the blowing of those straws he had so long observed with absorbed interest.

“Above all the common sounds of daily human life one hears in that one land the rattle and clash of arms and the unending thudding tread of marching feet,” he said after one such visit. “Two generations of men creatures bred and born and trained to live as parts of a huge death dealing machine have resulted in a monstrous construction. Each man is a part of it and each part’s greatest ambition is to respond to the shouted word of command as a mechanical puppet responds to the touch of a spring. To each unit of the millions, love of his own country means only hatred of all others and the belief that no other should be allowed existence. The sacred creed of each is that the immensity of Germany is such that there can be no room on the

Comments (0)