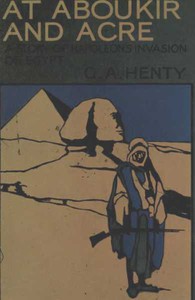

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt, G. A. Henty [top 10 inspirational books .txt] 📗

- Author: G. A. Henty

Book online «At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt, G. A. Henty [top 10 inspirational books .txt] 📗». Author G. A. Henty

The 28th Regiment stationed there opened a heavy fire on the force attacking them in front, but the flanking column, now joined by a third, forced its way in behind the battery. While some attacked it in the rear, the rest penetrated into the ruins held by the 58th. Its colonel wheeled back the left wing of the regiment, and after two or three volleys, fell on the French with the bayonet. At this moment the 23rd came up in support, and the 42nd advanced from the left, and, keeping on the outside of the ruins, cut off the troops which had entered, and after suffering heavy loss they were compelled to surrender.

The 28th had remained firmly at the front line of the redoubt, and they and the 58th had hitherto been supporting simultaneously attacks in front, flank, and rear. The arrival of the 42nd for a time relieved them, but as the latter regiment approached the right of the redoubt, the enemy's cavalry, which had passed round by its left, charged them furiously and broke them. The Highlanders, however, gathered in groups, and fought desperately until relieved by the fire of the flank companies of the 40th, and the cavalry, passing on, were about to charge this small force, when the foreign brigade came up from the second line and poured such a heavy fire into the French cavalry that they fled.

GIVING A YELL OF DERISION AND DEFIANCE

Page 323

As soon as the fire broke out, General Abercrombie, with his staff, mounted and proceeded towards the point where[Pg 329] the battle was raging. On the way he detached his aides-de-camp with orders to different brigades, and while thus alone with an escort of dragoons, some of the French cavalry dashed at him and he was thrown from his horse. A French officer rode up to cut him down, but he sprang at him, seized his sword, and wrested it from his hand. At that instant the officer was bayoneted by one of the 42nd.

Battle of ALEXANDRIA

arst. March 1801.

While this incident was proceeding Sir Ralph received a musket-ball in the thigh, and also a severe contusion on the breast, probably by a splinter of stone struck by a cannon-ball. In the heat of the action he was unconscious of the first wound, but felt much pain from the contusion. At this moment Sir Sidney Smith rode up; he had accidentally broken his sword, and the general discerning it, at once presented him with the one that he had wrested from the[Pg 330] French officer. He then took up his station in the battery, from which he could obtain a view of the whole scene of the battle, for by this time it was daylight. The contest still raged. Another body of cavalry charged the foreign brigade, but were received with so heavy a fire that they did not press the charge home. The French infantry were now no longer in column, but spread out everywhere in skirmishing order. The ammunition of the English on the right was by this time totally exhausted, and but one cartridge remained for each of the guns in the battery.

The chief point of attack was now the centre. Here a column of grenadiers, supported by a heavy line of infantry, advanced to the assault, but the Guards stoutly maintained themselves until General Coote, with his brigade, came up, and the French were then driven back. All this time the French guns kept up an incessant cannonade on the British position. The attack on the British left, which had been but a feint, was never seriously pursued, but was confined to a scattered fire of musketry and a distant cannonade. General Hutchinson, who commanded here, kept his force in hand; for, had he moved to the assistance of the centre and right, a serious attack might have been made on him, and the flank being thus turned, the position would have been taken in rear.

On the right the French as well as the British had exhausted their ammunition, and the singular spectacle was presented of two hostile forces pelting each other with stones, by which many heavy blows were given on both sides, and some killed, among them a sergeant of the 28th. The grenadiers and a company of the 40th presently moved out against the assailants, and the French then fell back. General Menou, finding that all his attacks had failed, now called off his troops. Fortunately for them the[Pg 331] artillery ammunition was now exhausted, but they lost a good many men by the fire of some British cutters, which had during the whole action maintained their position a short distance in advance of the British right, and greatly aided the defenders of the redoubt by their fire.

By ten o'clock the action was over. Until the firing ceased altogether Sir Ralph Abercrombie remained in the battery paying no attention to his wounds, and, indeed, the officers who came and went with orders were ignorant that he had been hit. Now, however, faint with loss of blood, he could maintain his position no longer, and was placed in a hammock and carried down to the shore, and rowed off to the flagship. As soon as the French had withdrawn, attention was paid to the wounded. The total loss was 6 officers and 230 men killed, 60 officers and 1190 men wounded. The French loss was heavier. 1700 French, killed and wounded, were found on the battlefield, and 1040 of these were buried on the field. Taking the general proportion of wounded and killed, the French loss, including the prisoners, amounted to 4000 men; one French standard and two guns were captured.

The total British force was under 10,000 men, of whom but half were seriously engaged. The French were about 11,000 strong, of whom all, save the 800 who made the feint on the British left, took part in the fighting. On the 25th the Capitan Pasha, with 6000 men, arrived in the bay, and landed and encamped. Three days later the army was saddened by the news of the death of Sir Ralph Abercrombie. He was succeeded in his command by General Hutchinson. For some time Edgar had an idle time of it. The French had failed in their attack, but they had not been defeated, and their position was too strong to be attacked. The Capitan Pasha had with him an excellent[Pg 332] interpreter, and therefore his services were not required in that capacity.

The night before the battle he stopped up all night talking with Sidi, relating all that had happened since he had left him, and hearing from him what had taken place on land. This was little enough. A great number of the Arabs had gathered in readiness to sweep down upon the French when they attacked the Turkish army at Aboukir, but when the latter had, with terrible slaughter, been driven into the castle, they had scattered to their homes. The next day the young Arab witnessed with delight the repulse of the French attack, and at the conclusion of the fight rode away to tell his father of Edgar's return, and of the events that he had witnessed. The sheik had come back with him on the following day, accompanied by some of his followers, and their tents were pitched on a sand-hill a short distance in the rear of the British lines.

Until April 13th nothing was done. The army was too small to undertake any operations, and was forced to remain in its position, as it might at any moment be again attacked.

In the pocket of General Roiz, who had been killed in the battle, was found a letter from General Menou, expressing fear that the English would cut the Canal of Alexandria and let the waters of it and Lake Aboukir into the old bed of Lake Mareotis. It was evident that an immense advantage would be gained by this. Our own left would be secure against attack. The French would be nearly cut off from the interior, and the British army be enabled to undertake fresh operations. General Hutchinson, however, hesitated for a long time before taking the step. A tract of rich country would be overwhelmed, and none of the Arabs could say how far the inundations would reach. However, the step was evidently so much to the advantage of the[Pg 333] army that at last he gave the order, and on the 13th of April the work began, and that evening the water rushed out from Lake Aboukir through two cuts. Others were opened the next day. The rush of water quickly widened these, and soon the inundation spread over a large tract of country behind Alexandria.

A considerable force was at once detached to support Colonel Spencer, who was menacing Rosetta, and marched to El Hamed. Sir Sidney Smith ascended the Nile with an armed flotilla as far as El Aft, and on the 19th aided the Turks in capturing Fort St. Julian, a strong place between Rosetta and the mouth of the Nile. After the fall of St. Julian, Rosetta was taken possession of with but little difficulty. Soon after this, to the deep regret of the navy, Sir Sidney Smith was recalled to his ship. The Grand Vizier had a serious grudge against him. This arose from a capitulation that had, shortly after the retreat of the French from Acre, been agreed upon between the Turkish authorities and the French, by which the latter were to be permitted to evacuate Egypt.

Sir Sidney Smith had not been consulted, but considering, and justly, that the advantages were great, had signed it. Lord Keith, as commander-in-chief, had refused to ratify the treaty, and the English government, who were in high spirits at the blow struck at the French at Acre, agreed with his action. Sir Sidney Smith, as soon as he received Lord Keith's despatch, sent a mounted messenger to Cairo to inform General Kleber that the terms of the convention were rejected. The despatch reached the French just as they were preparing to evacuate Cairo. Unfortunately, the Grand Vizier, who, with his army, was but a short distance away from the town, did not receive a similar intimation, and approaching the city with his troops, but[Pg 334] without guns, was attacked by the French, and suffered a disastrous defeat.

The Turks had not forgiven Sir Sidney Smith for this misfortune, but the latter had not supposed for a moment that the Turks themselves would have neglected to apprise the Grand Vizier of the news, and only thought of warning the French. The Grand Vizier now demanded that Sir Sidney Smith should not take part in any operations in which he and the Turkish army were concerned, or retain the command of the naval flotilla that he had created, and with which he had performed such excellent service in opening the Nile for the ascent of the gun-boats and the native craft laden with stores for the supply of the troops that were to advance against Cairo. General Hutchinson, very weakly and unworthily, and to the indignation and regret both of the army and fleet, at once gave way, and Admiral Keith, instead of supporting his subordinate, who had gained such renown and credit, and had shown such brilliant talent, acquiesced, and appointed Captain Stevenson of the Europa to succeed Sir Sidney in command of the flotilla that was to ascend the Nile to Cairo.

This surrender of one of our most distinguished officers to the prejudices of a Turkish commander was, in all respects, a disgraceful one, but from Sir Sidney Smith's first appointment Admiral Keith had exhibited a great jealousy of his obtaining a command that rendered him to some extent independent, and had lost no opportunity of showing his feeling. Indeed, there can be little doubt that the discourteous manner in which he repudiated, without any authority from the English government, the convention that would have saved all the effusion of blood and cost of the British expedition was the result of his jealousy of the fame acquired by Sir Sidney Smith. The latter, greatly[Pg 335] hurt at the unjust and humiliating manner in which he had been treated, at once returned to the Tigre, where the delight of the crew at being again under his

Comments (0)