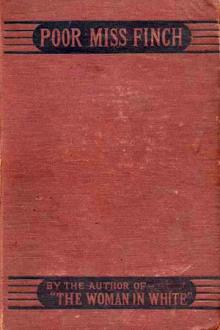

Poor Miss Finch, Wilkie Collins [the little red hen read aloud TXT] 📗

- Author: Wilkie Collins

- Performer: -

Book online «Poor Miss Finch, Wilkie Collins [the little red hen read aloud TXT] 📗». Author Wilkie Collins

At the first sound of his voice, I felt Lucilla start. Her hand began to tremble on my arm with some sudden agitation, inconceivable to me. In the double surprise of discovering this, and of finding myself charged so abruptly with the offense of looking at a gentleman, I suffered the most exceptional of all losses (where a woman is concerned)—the loss of my tongue.

He gave me no time to recover myself. He proceeded with what he had to say—speaking, mind, in the tone of a perfectly well-bred man; with nothing wild in his look, and nothing odd in his manner.

“Excuse me, if I venture on asking you a very strange question,” he went on. “Did you happen to be at Exeter, on the third of last month?”

(I must have been more or less than woman, if I had not recovered the use of my tongue now!)

“I never was at Exeter in my life, sir,” I answered. “May I ask, on my side, why you put the question to me?”

Instead of replying, he looked at Lucilla.

“Pardon me, once more. Perhaps this young lady–-?”

He was plainly on the point of inquiring next, whether Lucilla had been at Exeter—when he checked himself. In the breathless interest which she felt in what was going on, she had turned her full face upon him. There was still light enough left for her eyes to tell their own sad story, in their own mute way. As he read the truth in them, the man’s face changed from the keen look of scrutiny which it had worn thus far, to an expression of compassion—I had almost said, of distress. He again took off his hat, and bowed to me with the deepest respect.

“I beg your pardon,” he said, very earnestly. “I beg the young lady’s pardon. Pray forgive me. My strange behavior has its excuse—if I could bring myself to explain it. You distressed me, when you looked at me. I can’t explain why. Good evening.”

He turned away hastily, like a man confused and ashamed of himself—and left us. I can only repeat that there was nothing strange or flighty in his manner. A perfect gentleman, in full possession of his senses—there is the unexaggerated and the just description of him.

I looked at Lucilla. She was standing, with her blind face raised to the sky, lost in herself, like a person wrapped in ecstasy.

“Who is that man?” I asked.

My question brought her down suddenly from heaven to earth. “Oh!” she said reproachfully, “I had his voice still in my ears—and now I have lost it! ‘Who is he?’ ” she added, after a moment; repeating my question. “Nobody knows. Tell me—what is he like. Is he beautiful? He must be beautiful, with that voice!”

“Is this the first time you have heard his voice?” I inquired.

“Yes. He passed us yesterday, when I was out with Zillah. But he never spoke. What is he like? Do, pray tell me—what is he like?”

There was a passionate impatience in her tone which warned me not to trifle with her. The darkness was coming. I thought it wise to propose returning to the house. She consented to do anything I liked, as long as I consented, on my side, to describe the unknown man.

All the way back, I was questioned and cross-questioned till I felt like a witness under skillful examination in a court of law. Lucilla appeared to be satisfied, so far, with the results. “Ah!” she exclaimed, letting out the secret which her old nurse had confided to me. “You can use your eyes. Zillah could tell me nothing.”

When we got home again, her curiosity took another turn. “Exeter?” she said, considering with herself. “He mentioned Exeter. I am like you—I never was there. What will books tell us about Exeter?” She despatched Zillah to the other side of the house for a gazetteer. I followed the old woman into the corridor, and set her mind at ease, in a whisper. “I have kept what you told me a secret,” I said. “The man was out in the twilight, as you foresaw. I have spoken to him; and I am quite as curious as the rest of you. Get the book.”

Lucilla had (to confess the truth) infected me with her idea, that the gazetteer might help us in interpreting the stranger’s remarkable question relating to the third of last month, and his extraordinary assertion that I had distressed him when I looked at him. With the nurse breathless on one side of me, and Lucilla breathless on the other, I opened the book at the letter “E,” and found the place, and read aloud these lines, as follows:—

“EXETER: A city and seaport in Devonshire. Formerly the seat of the West Saxon Kings. It has a large foreign and home commerce. Population 33,738. The Assizes for Devonshire are held at Exeter in the spring and summer.”

“Is that all?” asked Lucilla.

I shut the book, and answered, like Finch’s boy, in three monosyllabic words:

“That is all.”

THERE had been barely light enough left for me to read by. Zillah lit the candles and drew the curtains. The silence which betokens a profound disappointment reigned in the room.

“Who can he be?” repeated Lucilla, for the hundredth time. “And why should your looking at him have distressed him? Guess, Madame Pratolungo!”

The last sentence in the gazetteer’s description of Exeter hung a little on my mind—in consequence of there being one word in it which I did not quite understand—the word “Assizes.” I have, I hope, shown that I possess a competent knowledge of the English language, by this time. But my experience fails a little on the side of phrases consecrated to the use of the law. I inquired into the meaning of “Assizes,” and was informed that it signified movable Courts, for trying prisoners at given times, in various parts of England. Hearing this, I had another of my inspirations. I guessed immediately that the interesting stranger was a criminal escaped from the Assizes.

Worthy old Zillah started to her feet, convinced that I had hit him off (as the English saying is) to a T. “Mercy preserve us!” cried the nurse, “I haven’t bolted the garden door!”

She hurried out of the room to defend us from robbery and murder, before it was too late. I looked at Lucilla. She was leaning back in her chair, with a smile of quiet contempt on her pretty face. “Madame Pratolungo,” she remarked, “that is the first foolish thing you have said, since you have been here.”

“Wait a little, my dear,” I rejoined. “You have declared that nothing is known of this man. Now you mean by that—nothing which satisfies you. He has not dropped down from Heaven, I suppose? The time when he came here, must be known. Also, whether he came alone, or not. Also, how and where he has found a lodging in the village. Before I admit that my guess is completely wrong, I want to hear what general observation in Dimchurch has discovered on the subject of this gentleman. How long has he been here?”

Lucilla did not, at first, appear to be much interested in the purely practical view of the question which I had just placed before her.

“He has been here a week,” she answered carelessly.

“Did he come, as I came, over the hills?”

“Yes.”

“With a guide, of course?”

Lucilla suddenly sat up in her chair.

“With his brother,” she said. “His twin brother, Madame Pratolungo.”

I sat up in my chair. The appearance of his twin-brother in the story was a complication in itself. Two criminals escaped from the Assizes, instead of one!

“How did they find their way here?” I asked next.

“Nobody knows.”

“Where did they go to, when they got here?”

“To the Cross-Hands—the little public-house in the village. The landlord told Zillah he was perfectly astonished at the resemblance between them. It was impossible to know which was which—it was wonderful, even for twins. They arrived early in the day, when the tap-room was empty; and they had a long talk together in private. At the end of it, they rang for the landlord, and asked if he had a bedroom to let in the house. You must have seen for yourself that The Cross-Hands is a mere beer-shop. The landlord had a room that he could spare—a wretched place, not fit for a gentleman to sleep in. One of the brothers took the room for all that.”

“What became of the other brother?”

“He went away the same day—very unwillingly. The parting between them was most affecting. The brother who spoke to us tonight insisted on it—or the other would have refused to leave him. They both shed tears–-”

“They did worse than that,” said old Zillah, re-entering the room at the moment. “I have made all the doors and windows fast, downstairs; he can’t get in now, my dear, if he tries.”

“What did they do that was worse than crying?” I inquired.

“Kissed each other!” said Zillah, with a look of profound disgust. “Two men! Foreigners, of course.”

“Our man is no foreigner,” I said. “Did they give themselves a name?”

“The landlord asked the one who stayed behind for his name,” replied Lucilla. “He said it was ‘Dubourg.’ “

This confirmed me in my belief that I had guessed right. “Dubourg” is as common a name in my country as “Jones” or “Thompson” is in England—just the sort of feigned name that a man in difficulties would give among us. Was he a criminal countryman of mine? No! There had been nothing foreign in his accent when he spoke. Pure English—there could be no doubt of that. And yet he had given a French name. Had he deliberately insulted my nation? Yes! Not content with being stained by innumerable crimes, he had added to the list of his atrocities—he had insulted my nation!

“Well?” I resumed. “We have left this undetected ruffian deserted in the public-house. Is he there still?”

“Bless your heart!” cried the old nurse, “he is settled in the neighborhood. He has taken Browndown.”

I turned to Lucilla. “Browndown belongs to Somebody,” I said hazarding another guess. “Did Somebody let it without a reference?”

“Browndown belongs to a gentleman at Brighton,” answered Lucilla. “And the gentleman was referred to a well-known name in London—one of the great City merchants. Here is the most provoking part of the whole mystery. The merchant said, ‘I have known Mr. Dubourg from his childhood. He has reasons for wishing to live in the strictest retirement. I answer for his being an honorable man, to whom you can safely let your house. More than this I am not authorized to tell you.’ My father knows the landlord of Browndown; and that is what the reference said to him, word for word. Isn’t it provoking? The house was let for six months certain, the next day. It is wretchedly furnished. Mr. Dubourg has had several things that he wanted sent from Brighton. Besides the furniture, a packing-case from London arrived at the house to-day. It was so strongly nailed up that the carpenter had to be sent for to open it. He reports that the case was full of thin plates of gold and silver; and it was accompanied by a box of extraordinary tools, the use of which was a mystery to the carpenter himself. Mr. Dubourg locked up these things in a room at the back of the house, and put the key in his pocket. He seemed to be pleased—he whistled a tune, and said, ‘Now we shall do!’

Comments (0)