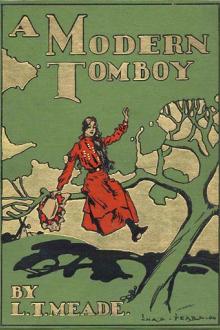

A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls, L. T. Meade [ready to read books .txt] 📗

- Author: L. T. Meade

Book online «A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls, L. T. Meade [ready to read books .txt] 📗». Author L. T. Meade

Just then Mrs. Brett was seen returning. Lucy stood up hastily. "I will talk to you. It would be best," she said then.

"To-night," said Rosamund—"to-night, after prayers, let us meet outside under the elm-trees. We can talk there and put things a bit straight. I don't think we can go on as we have begun. It would make us both unhappy."

"My dear girls," called out Mrs. Brett—"ah! I see the tea-things are all washed up and put away in the basket. Well, they will be quite safe; there are no gipsies in these parts. Now, who will come with me as far as the station? Don't all speak at once. I shall be very glad of the company of those who like to come; but those who don't may stay behind, and they won't offend me in the very least."

But all the girls wanted to accompany Mrs. Brett; and, surrounded by a crowd of eager young people, the good lady walked to the railway station.

CHAPTER IV. CASTING OF THE DIE.Rosamund and Jane Denton shared the same bedroom. They had been friends from childhood, for they had lived in the same street and gone to the same kindergarten together, and their mothers had been old school-fellows before marriage, so their friendship had grown up, as it were, with their very lives.

But Jane was a girl of no very special characteristics; she leant on Rosamund, admiring her far more vivacious ways and appearance, glad to be in her society, and somewhat indifferent to every one else in the wide world.

She sat now on a low and comfortable seat near the open window. Prayers were over, but the time that Rosamund had fixed for meeting Lucy Merriman had not quite arrived. She yawned and stretched herself luxuriously.

"I shall go to bed. Our work begins to-morrow. What are you sitting up for, Rosamund?"

"I am going out again in a few minutes," said Rosamund.

"Are you indeed?" cried Jane. "Then may I come with you? I shan't be a bit sleepy if I am walking out in the moonlight. But I thought——However, I suppose rules don't begin to-day."

"What do you mean by that?"

"I heard Miss Archer say that we were not to go out after half-past nine unless by special permission."

"Oh, well, as you remarked, rules don't begin until to-morrow, so I can go out at any hour I like to-night."

"I wonder why?" said Jane, and she looked up with a languid curiosity, which was all she could ever rise to, in her light-blue eyes.

Rosamund knelt by the window-sill; she put her arms on it and gazed out into the summer night. She heard people talking below her in the shrubbery. A few words fell distinctly on her ears, "I hate her, and I shall never be her friend!" and then the voices died away in the distance.

Jane had risen at that moment to fetch a novel which she was reading, so she did not hear what Rosamund had heard.

Rosamund's young face was now very white. There was a steady, pursed-up expression about her mouth. She suddenly slammed down the window with some force.

"What is it, Rose? What is the matter? Why shouldn't we have the window open on a hot night like, this?"

"Because I like it to be shut. You must put up with me as I am," said Rosamund. "I will open it if you wish in a few minutes. I have changed my mind, I am not going out. I shall go to bed. I have a severe headache."

"But wouldn't a walk in the moonlight with me, on our very last evening of freedom, take your headache away?" said Jane in a coaxing voice.

"No; I would rather not go out. You can do as you please. Only, creep in quietly when I am asleep. Don't wake me; that's all I ask."

"Oh, I'll just get into bed, dear, if you have a headache. But how suddenly it has come on!"

"This room is so stifling," she said. "After all, this is a small sort of school, and the rooms are low and by no means airy."

Jane could not help laughing.

"I never heard you talk in such a silly way before. Why, it was you who shut the window just now. How can you expect, on a hot summer's evening, the room to be cool with the window shut?"

"Well, fling it open—fling it open!" said Rosamund. "I don't mind."

Jane quickly did so. There was a crunching noise of steps—solitary steps—on the gravel below. Jane put out her head.

"Why, there is Lucy Merriman!" she said.

Lucy heard the voice, and looked up.

"Is Rosamund coming down? I am waiting for her," she said.

Jane turned at once to Rosamund.

"Lucy is waiting for you. Was it with Lucy you meant to walk? She wants to know if you are going down."

"Tell her I am not going down," replied Rosamund.

"She can't go down to-night," said Jane. "She has a headache."

"I wish you wouldn't give excuses of that sort," said Rosamund in an angry voice when her friend put in her head once more. "What does it matter to Lucy Merriman whether I have a headache or not?"

Jane stared at her friend in some astonishment.

"I do not understand you, nor why you wanted to walk with her. I thought you did not like her."

"I tell you what," said Rosamund fiercely, "I don't like her, and I'm not going to talk about her. I am going to ignore her. I am going to make this house too hot for her. She shall go and live with her aunt Susan, or she shall know her place. I, Rosamund Cunliffe, know my own power, and I mean to exercise it. It is the casting of the die, Jane; it is the flinging down of the gauntlet. And now, for goodness' sake, let us get into bed."

Both retired to rest, and in a few minutes Jane was fast asleep; but Rosamund lay awake for a long time, with angry feelings animating her breast.

In the morning the full routine of school-life began, and even Lucy was drawn into a semblance of interest, so full were the hours, so animated the way of the teachers, so eager and pleasant and stimulating the different professors. Then the English mistress, Miss Archer, knew so much, and was so tactful and charming; and Mademoiselle Omont knew her own tongue so beautifully, and was also such a perfect German scholar! In short, the seven girls had their work cut out for them, and there was not a minute's pause to allow ambition and envy and jealousy to creep in.

Lucy had one opportunity of asking Rosamund why she did not keep her appointment of the night before.

"You surprised me," she said. "I thought you were honorable and would keep your word. I had some difficulty in getting Miss Archer out of the way, for she was talking to me so nicely and so wisely, I can tell you, I was quite enjoying it. But I managed to get right away from her, and to walk under your window, and you never came."

"I suppose I was at liberty to change my mind," said Rosamund, her dark eyes flashing with anger.

"Oh! of course you were. But it would have been more polite to let me know. Not that it matters. I was not particularly keen to talk to you. I am so glad that Miss Archer is my friend. She gave me to understand last night how much she liked me, and how much she meant to help me with my studies. I believe from what she says that she considers I shall be quite the cleverest girl in the school. She believes in hereditary talent, and my dear father is a sort of genius, so, of course, as his only child, I ought to follow in his footsteps."

"Of course you ought," said Rosamund in a calm voice. "Then be the cleverest girl in the school."

"I mean to have a great try," said Lucy, with a laugh; and Rosamund gave her an unpleasant glance.

CHAPTER V. AN INVITATION.If any girl failed to enjoy herself on the following Saturday at Dartford, she had certainly only herself to blame. As a matter of fact, the whole seven, without exception, had a right good time. Even Lucy forgot her jealousies, and even Rosamund forgot her anger. They were so much interested in Mrs. Brett and her husband, in the things they did, and the things they could tell, and the things they could show, and the whole manner of their lives, that they forgot themselves.

Now, to forget yourself is the very road to bliss. Many people take a long time finding out that most simple secret. When they do find it out and act on it they invariably live a life of great happiness and equanimity, and are a great blessing to other people. Lucy and Rosamund were far—very far—from such a desirable goal, but for a few hours they did act upon this simple and noble idea of life, and in consequence were happy.

But Saturday at the Bretts', with all its bliss, came to an end, and the girls returned to beautiful Sunnyside and to the life of the new and rather strangely managed school.

Sunday was a long and dreary day, at least in Rosamund's eyes, and but for an incident which occurred immediately after morning service, she scarcely knew how she could have got through it.

Mr. Merriman had a pew at one end of the church, which had belonged to his people for generations, and which was not altered when the rest of the church was restored. It was large enough now to hold his wife and himself and the seven girls; but the two teachers were accommodated in another part of the church. Rosamund found herself during the service seated next to Mr. Merriman. It was the first time she had really closely observed him, and she now noticed several peculiarities which interested her a good deal. He had a dignified and very noble presence. He was tall, with broad shoulders, had an aquiline nose, very piercing dark eyes, black hair, which he wore somewhat long, and an olive-tinted face.

Lucy did not in the least resemble her father, but took more after her mother, who was round and fat, and proportionately commonplace. Rosamund at first felt no degree of elation when her place was pointed out to her next to the Professor. But suddenly encountering Lucy's angry eyes, she began to take a naughty comfort to herself in her unexpected proximity. She drew a little closer to him on purpose to annoy Lucy; and then, when she found that he was short-sighted and could not find his places, she found them for him, thus adding to poor Lucy's torment; for this had once been Lucy's own seat, and she herself had seen to her father's comforts. From attending on him, Rosamund began to watch him, and then she found a good deal of food for meditation. In short, it is to be feared that she did not follow the service as she ought to have done. For the matter of that, neither did Lucy.

The Rectory near Sunnyside was occupied by a clergyman who had several young daughters. These girls were very prepossessing in appearance. Their father was a widower, their mother having died some years ago. There were six girls, and as they trooped up the aisle, two by two, they attracted Rosamund's attention. They were dressed very simply in different shades of green. The two eldest had the darkest tone of color, both in their hats and their quiet little costumes. The two next had one shade lighter and the two youngest one shade lighter again. They looked something like leaves as they went up the church, and they all had one special characteristic—a great wealth of golden-brown hair, which hung far down their backs. The two eldest girls must have varied in age between fourteen and twelve, the two next between ten and eight, and the little ones between seven and five. They had quiet, neatly cut features, and serene eyes. They walked up the church very sedately, and took their places in the Rectory pew. Rosamund longed to ask a thousand questions about them. They were so much more interesting than the girls who were staying at Sunnyside; they were so fresh, and their dress so out of the common.

A somewhat prim and very neatly dressed governess followed the six girls up the aisle and took her place at the end of the

Comments (0)