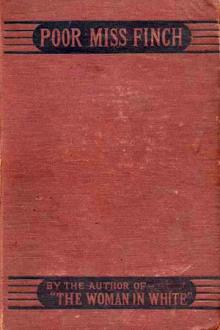

Poor Miss Finch, Wilkie Collins [the little red hen read aloud TXT] 📗

- Author: Wilkie Collins

- Performer: -

Book online «Poor Miss Finch, Wilkie Collins [the little red hen read aloud TXT] 📗». Author Wilkie Collins

The reckless, shameless composure with which he said that, began to set me against him once more. The perpetual shifts and contradictions in him, bewildered and irritated me. Quicksilver itself seemed to be less slippery to lay hold of than this man.

“Do you remember the day,” he asked, “when Lucilla lost her temper, and received you so rudely at your visit to Browndown?”

I made a sign in the affirmative.

“You spoke, a little while since, of my personating Oscar to her. I personated him, on the occasion I have just mentioned, for the first time. You were present and heard me. Did you care to speculate on the motives which made me impose myself on her as my brother?”

“As well as I can remember,” I answered, “I made the first guess that occurred to me. I thought you were indulging in a moment’s mischievous amusement at Lucilla’s expense.

“I was indulging the passion that consumed me! I longed to feel the luxury of her touching me and being familiar with me, under the impression that I was Oscar. Worse even than that, I wanted to try how completely I could impose on her—how easily I might marry her, if I could only deceive you all, and take her away somewhere by herself. The devil was in possession of me. I don’t know how it might have ended, if Oscar had not come in, and if Lucilla had not burst out as she did. She distressed me—she frightened me—she gave me back again to my better self. I rushed, without stopping to prepare her, into the question of her restoration to sight—as the only way of diverting her mind from the vile advantage that I had taken of her blindness. That night, Madame Pratolungo, I suffered pangs of self-reproach and remorse which would even have satisfied you. At the very next opportunity that offered, I made my atonement to Oscar. I supported his interests; I even put the words he was to say to Lucilla into his lips

“When?” I broke in. “Where? How?”

“When the two surgeons had left us. In Lucilla’s sitting-room. In the heat of the discussion whether she should submit to the operation at once—or whether she should marry Oscar first, and let Grosse try his experiment on her eyes at a later time. If you recall our conversation, you will remember that I did all I could to persuade Lucilla to marry my brother before Grosse tried his experiment on her sight. Quite useless! You threw all the weight of your influence into the opposite side of the scale. I failed. It made no difference. I had done what I had done in sheer despair: mere impulse—it didn’t last. When the next temptation tried me, I behaved like a scoundrel—as you say.”

“I have said nothing,” I answered shortly.

“Very well—as you think, then. Did you suspect me at last—when we met in the village, yesterday? Surely, even your eyes must have seen through me on that occasion!”

I answered silently, by an inclination of my head. I had no wish to drift into another quarrel. Sorely as he was presuming on my endurance, I tried, in Lucilla’s interests, to keep on friendly terms with him.

“You concealed it wonderfully well,” he went on, “when I tried to find out whether you had, or had not discovered me. You virtuous people are not bad hands at deception, when it suits your interests to deceive. I needn’t tell you what my temptation was yesterday. The first look of her eyes when they opened on the world; the first light of love and joy breaking on her heavenly face—what madness to expect me to let that look fall on another man, that light show itself to other eyes! No living being, adoring her as I adored her, would have acted otherwise than I did. I could have fallen down on my knees and worshipped Grosse, when he innocently proposed to me to take the very place in the room which I was determined to occupy. You saw what I had in my mind! You did your best—and did it admirably—to defeat me. Oh, you pattern people—you can be as shifty with your resources, when a cunning trick is to be played, as the worst of us! You saw how it ended. Fortune stood my friend at the eleventh hour; fortune can shine, like the sun, on the just and the unjust! I had the first look of her eyes! I felt the first light of love and joy in her face falling on me! I have had her arms round me, and her bosom on mine—”

I could endure it no longer.

“Open the door!” I said. “I am ashamed to be in the same room with you!”

“I don’t wonder at it,” he answered. “You may well be ashamed of me. I am ashamed of myself.”

There was nothing cynical in his tone, nothing insolent in his manner. The same man who had just gloried in that abominable way, in his victory over innocence and misfortune, now spoke and looked like a man who was honestly ashamed of himself. If I could only have felt convinced that he was mocking me, or playing the hypocrite with me, I should have known what to do. But I say again—impossible as it seems—he was, beyond all doubt, genuinely penitent for what he had said, the instant after he had said it! With all my experience of humanity, and all my practice in dealing with strange characters, I stopped mid-way between Nugent and the locked door, thoroughly puzzled.

“Do you believe me?” he asked.

“I don’t understand you,” I answered.

He took the key of the door out of his pocket, and put it on the table—close to the chair from which I had just risen.

“I lose my head when I talk of her, or think of her,” he went on. “I would give everything I possess not to have said what I said just now. No language you can use is too strong to condemn it. The words burst out of me: if Lucilla herself had been present, I couldn’t have controlled them. Go, if you like. I have no right to keep you here, after behaving as I have done. There is the key, at your service. Only think first, before you leave me. You had something to propose when you came in. You might influence me—you might shame me into behaving like an honorable man. Do as you please. It rests with you.”

Which was I, a good Christian? or a contemptible fool? I went back once more to my chair, and determined to give him a last chance.

“That’s kind,” he said. “You encourage me; you show me that I am worth trying again. I had a generous impulse in this room, yesterday. It might have been something better than an impulse—if I had not had another temptation set straight in my way.”

“What temptation?” I asked.

“Oscar’s letter has told you: Oscar himself put the temptation in my way. You must have seen it.”

“I saw nothing of the sort.”

“Doesn’t he tell you that I offered to leave Dimchurch for ever? I meant it. I saw the misery in the poor fellow’s face, when Grosse and I were leading Lucilla out of the room. With my whole heart, I meant it. If he had taken my hand, and had said Goodbye, I should have gone. He wouldn’t take my hand. He insisted on thinking it over by himself. He came back, resolved to make the sacrifice, on his side–-”

“Why did you accept the sacrifice?”

“Because he tempted me.”

“Tempted you?”

“Yes! What else can you call it—when he offered to leave me free to plead my own cause with Lucilla? What else can you call it—when he showed me a future life, which was a life with Lucilla? Poor, dear, generous fellow, he tempted me to stay when he ought to have encouraged me to go. How could I resist him? Blame the passion that has got me body and soul: don’t blame me!”

I looked at the book on the table—the book that he had been reading when I entered the room. These sophistical confidences of his were nothing but Rousseau at second hand. Good! If he talked false Rousseau, nothing was left for me but to talk genuine Pratolungo. I let myself go—I was just in the humour for it.

“How can a clever man like you impose on yourself in that way?” I said. “Your future with Lucilla? You have no future with Lucilla which is not shocking to think of. Suppose—you shall never do it, as long as I live—suppose you married her? Good heavens, what a miserable life it would be for both of you! You love your brother. Do you think you could ever really know a moment’s peace, with one reflection perpetually forcing itself on your mind? ‘I have cheated Oscar out of the woman whom he loved; I have wasted his life; I have broken his heart.’ You couldn’t look at her, you couldn’t speak to her, you couldn’t touch her, without feeling it all embittered by that horrible reproach. And she? What sort of wife would she make you, when she knew how you had got her? I don’t know which of the two she would hate most—you or herself. Not a man would pass her in the street, who would not rouse the thought in her—‘I wonder whether he has ever done anything as base as what my husband has done.’ Not a married woman of her acquaintance, but would make her sick at heart with envy and regret. ‘Whatever faults he may have, your husband hasn’t won you as my husband won me.’ You happy? Your married life endurable? Come! I have saved a few pounds, since I have been with Lucilla. I will lay you every farthing I possess, you two would be separated by mutual consent before you had been six months man and wife. Now, which will you do? Will you start for the Continent, or stay here? Will you bring Oscar back, like an honorable man? or let him go, and disgrace yourself for ever?”

His eyes sparkled; his color rose. He sprang to his feet, and unlocked the door. What was he going to do? To start for the Continent, or to turn me out of the house?

He called to the servant.

“James!”

“Yes, sir?”

“Make the house fast when Madame Pratolungo and I have left it. I am not coming back again.”

“Sir!”

“Pack my portmanteau, and send it after me tomorrow, to Nagle’s Hotel, London.”

He closed the door again, and came back to me.

“You refused to take my hand when you came in,” he said. “Will you take it now? I leave Browndown when you leave it; and I won’t come back again till I bring Oscar with me.

“Both hands!” I exclaimed—and took him by both hands. I could say

Comments (0)