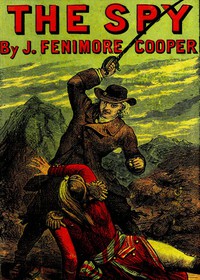

The Spy, James Fenimore Cooper [uplifting book club books TXT] 📗

- Author: James Fenimore Cooper

Book online «The Spy, James Fenimore Cooper [uplifting book club books TXT] 📗». Author James Fenimore Cooper

“Silence!” said the peddler, solemnly. “’Tis a name not to be mentioned, and least of all here, within the heart of the American army.” Birch paused and gazed around him for a moment, with an emotion exceeding the base passion of fear, and then continued in a gloomy tone, “There are a thousand halters in that very name, and little hope would there be left me of another escape, should I be again taken. This is a fearful venture that I am making; but I could not sleep in quiet, and know that an innocent man was about to die the death of a dog, when I might save him.”

“No,” said Henry, with a glow of generous feeling on his cheek, “if the risk to yourself be so heavy, retire as you came, and leave me to my fate. Dunwoodie is making, even now, powerful exertions in my behalf; and if he meets with Mr. Harper in the course of the night, my liberation is certain.”

“Harper!” echoed the peddler, remaining with his hands raised, in the act of replacing the spectacles. “What do you know of Harper? And why do you think he will do you service?”

“I have his promise; you remember our recent meeting in my father’s dwelling, and he then gave an unasked promise to assist me.”

“Yes—but do you know him? That is—why do you think he has the power?

Or what reason have you for believing he will remember his word?”

“If there ever was the stamp of truth, or simple, honest benevolence, in the countenance of man, it shone in his,” said Henry. “Besides, Dunwoodie has powerful friends in the rebel army, and it would be better that I take the chance where I am, than thus to expose you to certain death, if detected.”

“Captain Wharton,” said Birch, looking guardedly around and speaking with impressive seriousness of manner, “if I fail you, all fail you. No Harper nor Dunwoodie can save your life; unless you get out with me, and that within the hour, you die to-morrow on the gallows of a murderer. Yes, such are their laws; the man who fights, and kills, and plunders, is honored; but he who serves his country as a spy, no matter how faithfully, no matter how honestly, lives to be reviled, or dies like the vilest criminal!”

“You forget, Mr. Birch,” said the youth, a little indignantly, “that I am not a treacherous, lurking spy, who deceives to betray; but innocent of the charge imputed to me.”

The blood rushed over the pale, meager features of the peddler, until his face was one glow of fire; but it passed quickly away, as he replied,—

“I have told you truth. Caesar met me, as he was going on his errand this morning, and with him I have laid the plan which, if executed as I wish, will save you—otherwise you are lost; and I again tell you, that no other power on earth, not even Washington, can save you.”

“I submit,” said the prisoner, yielding to his earnest manner, and goaded by the fears that were thus awakened anew.

The peddler beckoned him to be silent, and walking to the door, opened it, with the stiff, formal air with which he had entered the apartment.

“Friend, let no one enter,” he said to the sentinel. “We are about to go to prayer, and would wish to be alone.”

“I don’t know that any will wish to interrupt you,” returned the soldier, with a waggish leer of his eye; “but, should they be so disposed, I have no power to stop them, if they be of the prisoner’s friends. I have my orders, and must mind them, whether the Englishman goes to heaven, or not.”

“Audacious sinner!” said the pretended priest, “have you not the fear of God before your eyes? I tell you, as you will dread punishment at the last day, to let none of the idolatrous communion enter, to mingle in the prayers of the righteous.”

“Whew-ew-ew—what a noble commander you’d make for Sergeant Hollister! You’d preach him dumb in a roll call. Harkee, I’ll thank you not to make such a noise when you hold forth, as to drown our bugles, or you may get a poor fellow a short horn at his grog, for not turning out to the evening parade. If you want to be alone, have you no knife to stick over the door latch, that you must have a troop of horse to guard your meetinghouse?”

The peddler took the hint, and closed the door immediately, using the precaution suggested by the dragoon.

“You overact your part,” said young Wharton, in constant apprehension of discovery; “your zeal is too intemperate.”

“For a foot soldier and them Eastern militia, it might be,” said Harvey, turning a bag upside down, that Caesar now handed him; “but these dragoons are fellows that you must brag down. A faint heart, Captain Wharton, would do but little here; but come, here is a black shroud for your good-looking countenance,” taking, at the same time, a parchment mask, and fitting it to the face of Henry. “The master and the man must change places for a season.”

“I don’t t’ink he look a bit like me,” said Caesar, with disgust, as he surveyed his young master with his new complexion.

“Stop a minute, Caesar,” said the peddler, with the lurking drollery that at times formed part of his manner, “till we get on the wool.”

“He worse than ebber now,” cried the discontented African. “A t’ink colored man like a sheep! I nebber see sich a lip, Harvey; he most as big as a sausage!”

Great pains had been taken in forming the different articles used in the disguise of Captain Wharton, and when arranged, under the skillful superintendence of the peddler, they formed together a transformation that would easily escape detection, from any but an extraordinary observer.

The mask was stuffed and shaped in such a manner as to preserve the peculiarities, as well as the color, of the African visage; and the wig was so artfully formed of black and white wool, as to imitate the pepper-and-salt color of Caesar’s own head, and to exact plaudits from the black himself, who thought it an excellent counterfeit in everything but quality.

“There is but one man in the American army who could detect you, Captain Wharton,” said the peddler, surveying his work with satisfaction, “and he is just now out of our way.”

“And who is he?”

“The man who made you prisoner. He would see your white skin through a plank. But strip, both of you; your clothes must be exchanged from head to foot.”

Caesar, who had received minute instructions from the peddler in their morning interview, immediately commenced throwing aside his coarse garments, which the youth took up and prepared to invest himself with; unable, however, to repress a few signs of loathing.

In the manner of the peddler there was an odd mixture of care and humor; the former was the result of a perfect knowledge of their danger, and the means necessary to be used in avoiding it; and the latter proceeded from the unavoidably ludicrous circumstances before him, acting on an indifference which sprang from habit, and long familiarity with such scenes as the present.

“Here, captain,” he said, taking up some loose wool, and beginning to stuff the stockings of Caesar, which were already on the leg of the prisoner; “some judgment is necessary in shaping this limb. You will have to display it on horseback; and the Southern dragoons are so used to the brittle-shins, that should they notice your well-turned calf, they’d know at once it never belonged to a black.”

“Golly!” said Caesar, with a chuckle, that exhibited a mouth open from ear to ear, “Massa Harry breeches fit.”

“Anything but your leg,” said the peddler, coolly pursuing the toilet of Henry. “Slip on the coat, captain, over all. Upon my word, you’d pass well at a pinkster frolic; and here, Caesar, place this powdered wig over your curls, and be careful and look out of the window, whenever the door is open, and on no account speak, or you will betray all.”

“I s’pose Harvey t’ink a colored man ain’t got a tongue like oder folk,” grumbled the black, as he took the station assigned to him.

Everything now was arranged for action, and the peddler very deliberately went over the whole of his injunctions to the two actors in the scene. The captain he conjured to dispense with his erect military carriage, and for a season to adopt the humble paces of his father’s negro; and Caesar he enjoined to silence and disguise, so long as he could possibly maintain them. Thus prepared, he opened the door, and called aloud to the sentinel, who had retired to the farthest end of the passage, in order to avoid receiving any of that spiritual comfort, which he felt was the sole property of another.

“Let the woman of the house be called,” said Harvey, in the solemn key of his assumed character; “and let her come alone. The prisoner is in a happy train of meditation, and must not be led from his devotions.”

Caesar sank his face between his hands; and when the soldier looked into the apartment, he thought he saw his charge in deep abstraction. Casting a glance of huge contempt at the divine, he called aloud for the good woman of the house. She hastened at the summons, with earnest zeal, entertaining a secret hope that she was to be admitted to the gossip of a death-bed repentance.

“Sister,” said the minister, in the authoritative tones of a master, “have you in the house `The Christian Criminal’s last Moments, or Thoughts on Eternity, for them who die a violent Death’?”

“I never heard of the book!” said the matron in astonishment.

“’Tis not unlikely; there are many books you have never heard of: it is impossible for this poor penitent to pass in peace, without the consolations of that volume. One hour’s reading in it is worth an age of man’s preaching.”

“Bless me, what a treasure to possess! When was it put out?”

“It was first put out at Geneva in the Greek language, and then translated at Boston. It is a book, woman, that should be in the hands of every Christian, especially such as die upon the gallows. Have a horse prepared instantly for this black, who shall accompany me to my brother—, and I will send down the volume yet in season. Brother, compose thy mind; you are now in the narrow path to glory.”

Caesar wriggled a little in his chair, but he had sufficient recollection to conceal his face with hands that were, in their turn, concealed by gloves. The landlady departed, to comply with this very reasonable request, and the group of conspirators were again left to themselves.

“This is well,” said the peddler; “but the difficult task is to deceive the officer who commands the guard—he is lieutenant to Lawton, and has learned some of the captain’s own cunning in these things. Remember, Captain Wharton,” continued he with an air of pride, “that now is the moment when everything depends on our coolness.”

“My fate can be made but little worse than it is at present, my worthy fellow,” said Henry; “but for your sake I will do all that in me lies.”

“And wherein can I be more forlorn and persecuted than I now am?” asked the peddler, with that wild incoherence which often crossed his manner. “But I have promised one to save you, and to him I have never yet broken my word.”

“And who is he?” said Henry, with awakened interest.

“No one.”

The man soon returned, and announced that the horses were at the door. Harvey gave the captain a glance, and led the way down the stairs, first desiring the woman to leave the prisoner to himself, in order that he might digest the wholesome mental food that he had so lately received.

A rumor of the odd character of the priest had spread from the sentinel at the door to his comrades; so that when Harvey and Wharton reached the open space before the building, they found a dozen idle dragoons loitering about with the waggish intention of quizzing the fanatic, and employed in affected admiration of the steeds.

“A fine horse!” said the leader in this plan of mischief; “but a little low in flesh. I suppose from hard labor in your calling.”

“My calling may be laborsome to both myself and this faithful beast, but then a day of settling is at hand, that will reward me for all my outgoings and incomings,” said Birch, putting his foot in the stirrup, and preparing to mount.

“You work for pay, then, as we fight for’t?” cried another of the party.

“Even so—is not the laborer worthy of his hire?”

“Come, suppose you give us a little preaching; we have a leisure moment just now, and there’s no

Comments (0)