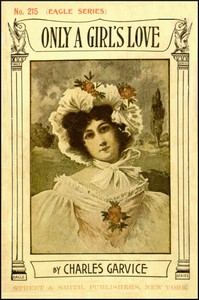

Only a Girl's Love, Charles Garvice [a book to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Garvice

Book online «Only a Girl's Love, Charles Garvice [a book to read .txt] 📗». Author Charles Garvice

"Stella, I have been waiting month after month to say what I am going to say now; but I couldn't wait any longer, my darling, my own, I wish the marriage to take place."

She did not start, but she turned and looked at him, and her face shone whitely in the darkness, and he felt a faint shudder in the hand imprisoned in his.

"Will you not speak?" he said, after a moment, almost angry, because of the tempest of passion and breathed tenderness that possessed him. "Have you nothing to say, or will you say 'no?' I almost expect it."

"I will not say no," she said, at last, and her voice was cold and strained. "You have a right—the right I have given you—to demand the fulfillment of our bargain."

"Good Heaven!" he broke in, passionately. "Why do you talk like this? Shall I never, never win you to love me? Will you never forget how we came together?"

"Do not ask me," she said, almost pleaded, and her face quivered. "Indeed—indeed, I try, try—try hard to forget the past, and to please you!"

It was piteous to hear and see her, and his heart ached; but it was for himself as well as for her.

"Do you doubt my love?" he said, hoarsely. "Do you think any man could love you better than I do? Does that count as nothing with you?"

"Yes, yes," she said, slowly, sadly. "It does count. I—I——" then she looked down. "Why will you speak of love between us?" she said. "Ask me—tell me to do anything, and I will do it, but do not speak of love!"

He bit his lip.

"Well," he said, with an effort, "I will not. I see I cannot touch your heart yet. But the time will come. You cannot stand against a love like mine. And you will let our marriage be soon?"

"Yes," she said, simply.

[237]

He raised her hand to his lips, and kissed it, hungrily, and she forced back the shudder which threatened to overmaster her.

"By soon," he murmured, as they walked toward the house, "I mean quite soon—before the winter."

Stella did not speak.

"Let it be next month, darling," he murmured. "I shall not feel sure of you until you are my very own. Once you are mine beyond question, I will teach you to love me."

Stella looked at him, and a strange, despairing smile, more bitter and sad than tears, shone on her pale lips. Teach her to love him! As if love could be taught!

"I am not afraid," he said, answering her smile; "no one could withstand it—not even you, though your heart were adamant."

"It is not that," she said, in a low voice, as she thought of the dull aching which was its pittance by day and night.

They went into the house. Mr. Etheridge was wandering about the room, smoking his pipe, his head upon his breast, buried in thought, as usual. Frank was lying back in the old arm-chair; he looked wearily-fragile and delicate, but the beautiful color shone in his face.

He looked up and nodded as Jasper entered, but Jasper was not satisfied with the nod, and went over to him and laid a hand upon his shoulder, at which the boy winced and shrank faintly; he never could bear Jasper to touch him, and always resented it.

"Well, Frank," he said, with his faint smile, "how's the cold to-night?"

Frank murmured something indistinctly, and shifted in his seat.

"Not so well, eh?" said Jasper. "It seems to me that a change would do you good. What do you say to going away for a little while?"

The boy looked up at Stella with a glance of alarm. Leave Stella!

"I don't want to go away," he said, shortly. "I am quite well. I hate a change."

Stella came up to his chair, and knelt beside him.

"It would do you good, dear," she said, in her low, musical voice.

He bent near her.

"Do you mean—alone?" he asked. "I don't want to go alone—I won't, in fact."

"No, not alone, certainly," said Jasper, with his smile. "I think some one else wants a change too."

And he looked at Stella tenderly.

"I'll go if Stella goes," said Frank, curtly.

"What do you say, sir?" said Jasper to the old man.

He stared, and the proposal had to be put to him in extenso; he had not heard a word of what had been said.

"Go away! yes, if you like. But why? Frank's cold? I don't suppose any other place is better for a cold is it? It is? Very well then. You don't want me to come, I suppose?"

"Well——" said Jasper.

[238]

"I couldn't do it!" exclaimed the old man, almost with alarm. "I should be like a fish out of water. I couldn't paint away from the river and the meadows. Oh, it's impossible! Besides, you don't want an old man pottering about," and he looked at Stella and smiled grimly.

"I couldn't go without you," said Stella, quietly.

"Nonsense," he said; "there's the other old woman, Mrs. Penfold, take her; she can go. It will do her good, though she hasn't a cold."

Then he stopped in front of the boy and looked at him, with the strange reserved, almost sad, expression which always came upon his race when he regarded him.

"Yes," he said, in a low voice; "he wants a change. I haven't noticed; he looks thin and unwell. Yes, you had better go! Where will you go?"

Stella shook her head with a smile, but Jasper was ready.

"Let me see," he said, thoughtfully. "We don't want a cold place, the change would be too great; and we don't want too hot a place. What do you say to Cornwall?"

The old man nodded.

Stella smiled again.

"I haven't anything to say," she said. "Would you like Cornwall, Frank?"

He looked from one to the other.

"What made you think of Cornwall?" he asked Jasper, suspiciously.

Jasper laughed softly.

"It seemed to me just the place to suit you. It is mild and clear, and just what you want. Besides, I remember a little place near the sea, a sheltered village in a bay—Carlyon they call it—that would just do for us. What do you say? Let me see, where is the map?"

He went and got a map and spreading it out on the table, called to Stella.

"This is it," he said, then in a low voice he whispered: "There is a pretty, secluded little church there, Stella. Why should we not be married there?"

She started, and her hand fell on the map.

"I am thinking of you, my darling," he said. "For my part I should like to be married here——"

"No, not here," she faltered, as she thought of standing before the altar in the Wyndward Church and seeing the white walls of the Hall as she uttered her marriage vow. "Not here."

"I understand," he said. "Then why not there? Your uncle could come down for that, I think."

She did not speak, and with a smile of satisfaction he folded the map.

"It is all settled," he said. "We go to Carlyon. You will come down for a little while, I hope, sir. We shall want you."

The old man pushed the white hair off his forehead.

"Eh?" he asked. "What for?"

"To give Stella away," replied Jasper. "She has promised to marry me there."

[239]

The old man looked at her.

"Why not here?" he asked, naturally, but Stella shook her head.

"Very well," he said. "It is a strange fancy, but girls are fanciful. Off you go, then, and don't make more fuss than you can help."

So Stella's fate was settled, and the day, the fatal day, loomed darkly before her.

CHAPTER XXXVI.Lord Charles was too glad to gain Leycester's consent to leave town to care where they went, and to prevent all chance of Leycester's changing his mind, this stanch and constant friend went with him to his rooms and interviewed the patient Oliver.

"Go away, sir?" said that faithful and long-suffering individual. "I'm glad of it! His lordship—and you too, begging your pardon, my lord—ought to have gone long ago. It's been terrible hot work these last few weeks. I never knew his lordship so wild. And where are we going, my lord?"

That was the question. Leycester rendered no assistance whatever, beyond declaring that he would not go where there was a houseful of people. He had thrown himself into a chair, and sat moodily regarding the floor. Bellamy's sudden illness and prophetic words had given him a shock. He was quite ready to go anywhere, so that it was away from London, which had become hateful to him since the last hour.

Lord Charles lit a pipe, and Oliver mixed a soda-and-brandy for him, and they two talked it over in an undertone.

"I've got a little place in the Doone Valley, Devonshire, you know," said Lord Charles, talking to Oliver quite confidentially. "It's a mere box—just enough for ourselves, and we should have to rough it, rough it awfully. But there's plenty of game, and some fishing, and it's as wild as a March hare!"

"That's just what his lordship wants," said Oliver. "I know him so well, you see, my lord. I must say that I've taken the way we've been going on lately very serious; it isn't the money, that don't matter, my lord; and it isn't altogether the wildness, we've been wild before, my lord, you know."

Lord Charles grunted.

"But that was only in play like, and there is no harm in it; but this sort of thing that's being going on hasn't been play, and it ain't amused his lordship a bit; why he's more down than when we came up."

"That's so, Oliver," assented Lord Charles, gloomily.

"I don't know what it was, and it isn't for me to be curious, my lord," continued the faithful fellow, "but it's my opinion that something went wrong down at the Hall, and that his lordship cut up rough about it."

Lord Charles, remembering that letter and the beautiful girl at the cottage, nodded.

"Perhaps so," he said. "Well, we'll go down to the Doone[240] Valley. Better pack up to-night, or rather this morning. I'll go home and get a bath, and we'll be off at once. Fish out the train, will you?"

Oliver, who was a perfect master of "Bradshaw," turned over the leaves of that valuable compilation, and discovered a train that left in the afternoon, and Lord Charles "broke it" to Leycester.

Leycester accepted their decision with perfect indifference.

"I shall be ready," he said, in a dispassionate, indifferent way. "Tell Oliver what you want."

"It's a mere box in a jungle," said Lord Charles.

"A jungle is what I want," said Leycester, grimly.

With the same grim indifference he started by that afternoon train, smoking in silence nearly all the way down to Barnstaple, and showing no interest in anything.

Oliver had telegraphed to secure seats in the coach that leaves that ancient town for the nearest point to the Valley, and early the next morning they arrived.

A couple of horses and a dogcart had been sent on—how Oliver managed to get them off was a mystery, but his command of resources at most times amounted to the magical—and they drove from Teignmouth to the Valley, and reached the "Hut," as it was called.

It was in very truth a mere box, but it was a box set in the center of a sportsman's paradise. Lonely and solitary it stood on the edge of the deer forest, within sound of a babbling trout-stream, and in the center of the best shooting in Devonshire.

Oliver, with the aforesaid magic, procured a couple of servants, and soon got the little place in order; and here the two friends lived, like hermits in a dell.

They fished and shot and rode all day, returning at night to a plain, late dinner; and altogether led a life so different to that which they had been leading as it was possible to imagine.

Lord Charles enjoyed it. He got brown, and as fit and "as hard as nails," as he described it, but Leycester took things differently. The gloom which had settled upon him would not be dispelled by the mountain air and the beauty of the exquisite valley.

Always and ever there seemed some cloud hanging over him, spoiling his enjoyment and witching the charm from his efforts at amusement. While Charles was killing trout in the stream, or dropping the pheasants in the moors, Leycester would wander up and down the valley, gun or rod in hand, using neither, his head drooping, his eyes fixed in gloomy retrospection.

In simple truth he was haunted by a spirit which clung to him now as it had clung to him in those days of feverish gayety and dissipation.

The vision of the slim, beautiful girl whom he loved was ever before him, her face floated between him and the mountains, her voice mingled with

Comments (0)