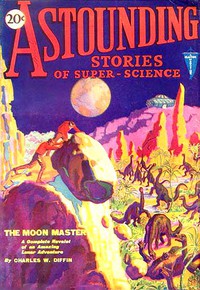

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930, Various [best large ereader txt] 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930, Various [best large ereader txt] 📗». Author Various

Moodily Sarka stared into the depths of the Beryl, which represented the Earth, and in which he could see everything that earthlings did, after visually enlarging them, through use of a microscope that could be adjusted, with relation to the Beryl, to bring out in detail any section of the world he wished to study. His face was utterly sad. The people at last truly possessed the Earth—all of it that was, even with the aid of every miracle known to science, habitable.

The surface of the Earth was one vast building, like a hive, and to each human being was allotted by law a certain abiding place. But men no longer died, unless they desired to do so, and then only when the Spokesmen of the Gens saw fit to grant permission; and there soon would be no place for the newborn to live. Even now that point had practically been reached throughout the world, and in the greater portion it had been reached, and passed, and men knew that while men did not die, they could be killed!

The vast building, towering above what had once been the surface of the earth, to heights undreamed of before the discovery, was irregular on its top,[Pg 21] to fit the contour of the earth, and its roof, constructed of materials raped from the earth's core, was so designed as to catch and concentrate the yearly more feeble rays of the sun, so that its life-giving warmth might continue to be the boon of living people.

It had been found as Earth cooled that life was possible to a depth of eight miles below the one-time surface, so that the one huge building extended below the surface to this great depth, and was divided and re-divided to make homes for men, their wives, and their progeny. But even so, space was limited. Neighboring families outgrew their surroundings, overflowed into the habitations of their neighbors—and every family was at constant war against its neighbors.

Men did not die, but they could be slain, and there was scarcely a home, above or below, in all the vast building, which had not planned and executed murder, times and times—or which had not left its own blood in the dwelling places of neighbors.

No law could cope with this intolerable situation, for men, down the ages, had changed in their essential characteristics but little—and recognized one law only in their extremity, that of self-preservation.

So there was murder rampant, and mothers who wept for children, husbands, fathers or mothers, who would never return to their homes.

"My grandfather," whispered Sarka, his eyes peering deeply into a certain area beyond that assigned by law to the House of Cleric, where men of two neighboring families were locked in mortal, silent conflict, "should not have frustrated the mad scheme of Dalis! It was slaughter, wholesale and terrible, but it would have cleansed the souls of the survivors!"

Mentally Sarka was looking back now to that red day when Dalis, the closest scientific rival of Sarka the First, had come to Sarka the First with his proposal which at the time had seemed so hideous. Sarka remembered that interval in all its details, for he had heard it many times.

"Sarka," Dalis had said in his high-pitched voice, staring at Sarka the First out of red-rimmed, fiery eyes, "unless something is done the world will rush on to self-destruction! Men will slay one another! Fathers will kill their sons, and sons their fathers, if something is not done! For always there is marrying and giving in marriage, and each family is reaching out in all directions, seeking merely space in which to live. Formerly there were wars which automatically took thought of the overplus of men; but to-day the world is at peace, as men regard the term—and every man's hand is against his neighbor! There will be no more wars, when there should be! There is but one alternative!"

"And that?" Sarka the First had queried suspiciously.

"The segregation of the fittest! The destruction, swiftly, painlessly, of all the others! And when the survivors have again re-populated the earth to overflowing—a repetition of the same corrective! Men will die, yes, by millions; but those who are left will be a stronger, sturdier race, and by this process of elimination, century by century, men will evolve and become super-men!"

"And this plan of yours?"

For a moment Dalis had paused, breathing heavily, as though almost afraid to continue. Then, while Sarka the First had listened in frozen terror, Dalis had explained his ghastly scheme.

"If it were not for the mountains and the valleys," said Dalis, "and the world were perfectly round and smooth of surface, that surface would be covered by water to the depth of one mile! Is that not correct! The Earth, rotating on its axis, travels about the sun at the rate of something like nineteen miles per second, so perfectly balanced that[Pg 22] the oceans remain almost quiescent in their beds! But, Sarka, mark me well! If we could, together, devise a way to halt this rotation for as much as a few seconds, what would happen?"

"What would happen?" repeated Sarka the First, dropping his own voice to a husky, frightened whisper. "Why, the oceans would be hurled out of their beds, and a wall of water a mile high or more—it is all guesswork!—would rush eastward around the world, bearing everything before it! It would uproot and destroy buildings, sweep the rocky covering of the earth free of soil; and humanity, caught on the earth below the highest level of the world's greatest tidal wave, would be engulfed!"

"Exactly!" Dalis had said with a grin. "Exactly! Only—the people we wish to survive could be warned, and these could either be aloft when the tidal wave swept the face of the earth, or could be safely out of reach of the waters on the sides of the highest mountains!"

Sarka the First, wanly smiling, catching his breath at last, now that he realized the utter impossibility of this mad scheme, had been minded to humor the fancies of a man whom he had believed not quite sane.

"Why not," he began, "take away from men the Secret of Life, so that they will die, as formerly, when the world was young?"

"When all the world knows the Secret, when even children learn it before they are capable of walking?" demanded Dalis sarcastically. "You could only remove knowledge of the Secret from the brains of men by removing those brains themselves! Your thought is more terrible even than mine, because it leads to this inescapable conclusion!"

"But supposing for a moment your mad scheme were possible, who should say whom, of all the earth's people, should be saved, whom sacrificed?"

"What better test could be given than that which I am proposing?" Dalis had snarled. "Those worthy of being saved would save themselves! Those who would perish would not be worth saving! As natural, as inescapable as the law of the survival of the fittest, which has been an axiom of life since men first crawled out of the slime and asked each other questions as they caught their first glimpses of the stars and pondered the reasons for them!"

"But where, then, was there any point in my giving to people the Secret of Life?"

"Had you paused to think," snapped Dalis, "you would never have done so! Your lust for power, and for fame, destroyed your foresight!"

"

And is it not, Dalis," replied Sarka the First, softly, "for this, really, that you have come to me? To berate me? To throw at my head mad schemes impossible of accomplishment? I have always known you for an enemy, Dalis, because you are envious of what I have accomplished, what you sense that I will accomplish as time passes!"

"I do not love you, Sarka!" retorted Dalis frankly. "I despise you! Hate you! But I need the aid of that keen brain of yours! You see, hate you though I may, I do you honor still. I have something up here," tapping the dome of his brow, only less lofty than that of Sarka, "which you lack. You have something I have not, never can attain! But together we are complements, each of the other, and to the two of us this scheme is possible!"

"I am very busy, Dalis," Sarka the First had replied coldly. "I must ask you to leave me! What you propose is impossible, unthinkable!"

"So," retorted Dalis, "you think me mad? You think me incapable of perfecting this plan about whose details you have not even yet been informed! You would show me the door as though you were a king and I a slave—when kings and slaves vanished from the[Pg 23] earth millenniums ago! Then listen to me, Sarka! I know how to do this thing about which I have told you. I can halt, for a brief moment only, the whirl of the earth about its axis. And by so doing I can flood the earth with the waters of the oceans! If you will not listen to me, I shall do it myself! You shall have two days in which to give me an answer, for I admit that I need you, who would balance me, make sure I made no fatal mistakes! But if you do not, I will act ... along the lines I have hinted!"

Apparently as unconcerned as though he had not just listened to a scheme for almost total depopulation of the world, the destruction of millions upon millions of lives, Sarka the First had dismissed Dalis—who had straightway used all his offices to arouse the world of science against the first Sarka.

But, when the two days of grace given by Dalis had passed, there were no oceans—for Sarka the First had been planning for a century against the time when the earth must of necessity be over-populated, and had worked and slaved in his laboratory against the contingency which had developed.

He had smiled, though there was a trace of fear on his face after Dalis had left, for his scheme had been worked out—not to destroy, but to save!

And from this same laboratory in which Sarka now sat and pondered on the next step in man's expansion, Sarka the First had, in fear and trembling at first, but with his confidence growing by leaps and bounds, worked his own miracle. Untold millions and billions of rays, whose any portion of which, coming in contact with water, immediately separated its hydrogen and oxygen, thus disintegrating its molecules, were hurled forth from their store-houses beneath the laboratory, across the faces of the mighty oceans of Earth....

And when men saw the miracle, they rushed into the mighty valleys where the oceans had been, and began to build new homes!

That had been centuries ago—scores of centuries.

Now all the earth, all the livable part of the earth, above its surface—and below it to the depths of miles—was filled with people, like bees in a monster hive, like ants of antiquity in their warrened hills. And there was no place now that they could go.

So they fought among themselves for the right to live.

"But my grandfather was right!" Sarka almost screamed it, speaking aloud in the silence of his laboratory. "My grandfather was right! Dalis was wrong! Science should be the science of Life, not of Death! Yet whither shall we go! Where now shall we find places for our people who are daily being born in myriads, to live, and love and flourish?"

But there was no answer. Only the humming of the perpetually revolving Beryl, which showed to the sad eyes of Sarka that the people of his beloved earth were rushing onward to Chaos, unless....

"If only I could be sure about Jaska!" he moaned. "If only my courage were as great as that of which I stand in need! For if I fail, even Dalis, had he succeeded with that scheme of his in grandfather's time, would be less a monster, less a criminal!"

CHAPTER III The Spokesmen of the GensFor a long moment Sarka looked broodingly out across the world beyond the metalized glass which formed the curving dome of his laboratory roof. There was little that could be seen, for always the mighty, cold winds, ruffed with flurries of snow and particles of ice, swept over this artificial roof of the world. Here and there huge portions of the area within the range of his normal vision were swept clear and clean

Comments (0)