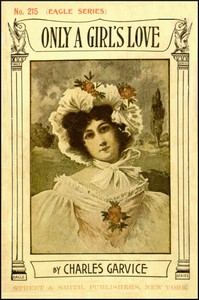

Only a Girl's Love, Charles Garvice [a book to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Garvice

Book online «Only a Girl's Love, Charles Garvice [a book to read .txt] 📗». Author Charles Garvice

"Listen to me," he said, hoarsely, "to-morrow I either give this paper"—and he snatched the forged bill from his breast pocket and struck it viciously with his quivering hand—"I either give it into your hands as my wife, or I give it to the[264] nearest magistrate. The boy will die! It rests with you whether he dies at peace or in a jail."

White and trembling she sat and looked at him.

"This is my answer to your pretty prayer," he said, with a bitterness incredible. "It is for you to decide—I use no further argument. Soft speeches and loving words are thrown away upon you; besides, the time has passed for them. There is no love, no particle of love, in my heart for you to-night—I simply stand by my bond."

She did not answer him, she scarcely heard him; she was thinking of that sad face that had appeared to her for a moment as if in reproach, and vanished ghost-like; and it was to it that she murmured:

"Oh, my love—my love!"

He heard her; and his face quivered with speechless rage; then he laughed.

"You made a great mistake," he said, with a sneer—"a very great mistake, if you are invoking Lord Leycester Wyndward. He may be your love, but you are not his! It is a matter of small moment—it does not weigh a feather in the balance between us—but the truth is, 'your love' is now Lady Lenore Beauchamp's!"

Stella looked up at him, and smiled wearily.

"A lie? No," he said, shaking his head tauntingly. "I have known it for weeks past. It is in every London paper. But that is nothing as between you and me—I stand by my bond. To-morrow the boy's fate lies in your hands or in that of the police. I have no more to say—I await your answer. I do not even demand it to-night—no doubt you would be——"

She arose, white and calm, her eyes fixed on him.

"—I say I await your answer till to-morrow. Acts, not words, I require. Fulfill your part of the bargain, and I will fulfill mine."

As he spoke he folded the forged bill which, in his excitement, had blown open, and put it slowly into his pocket again; then he wiped his brow and looked at her, biting his lip moodily.

"Will you come with me now," he said, "or will you wait and consider your course of action?"

His question seemed to rouse her; she raised her head, and disregarding his proffered arm, went slowly past him to the house.

He followed her for a few steps, then stopped, and with his head on his breast, went toward the cliffs. His fury had expended itself, and left a confused, bewildering sensation behind. For the time it really seemed, as he said, that his baffled love had turned to hate. But as he thought of her, recalling her beauty, his hate shrank back and returned to its old object.

"Curse him!" he hissed, "it is he who has done this! If he had not come to-night this would not have happened. Curse him! From the first he has stood in my path. Let her go! To him! Never! No, to-morrow she shall be mine in spite of him, she cannot draw back, she will not!"

Then his brain cleared; he began to upbraid himself for his[265] violence. "Fool, fool!" he muttered, hoarsely, as he climbed the path, scarcely heeding where he went. "I have lost her love forever! Why did I not bear with her a few hours longer? I have borne with her so long that I should have borne with her to the end! It was that cry of hers that maddened me! Heaven! to think that she should love him so; that she should have clung to him so persistently, him whom she had not seen for months, and keep her heart steeled against me who have hung about her like a slave! But I will be her slave no longer, to-morrow makes me her master."

As he muttered this sinister threat, he found that he had reached the end of the cutting that had been made in the cliff, and turned mechanically. The wind was blowing from the sea, and the sound of the waves rose from the depths beneath, crying hoarsely and complainingly as if in harmony with his mood. He paused a moment and looked down abstractedly.

"I would rather have her lying dead there," he muttered, "than that there should be a chance of her going back to him. No! he shall never have her. To-morrow shall set that fear at rest forever. To-morrow!" With a long breath he turned from the edge of the cliff, to descend, but as he did so he felt a hand on his arm, and looking up he saw the thin, frail figure of the boy standing in the path.

He was so wrapt in his own thoughts that he was startled, and made a movement to throw the hand off roughly, but it stuck fast, and with an effort to command himself, he said:

"Well, what are you doing up here?"

As he put the question, he saw by the fading light that the boy's face was deathly white—that for once the beautiful, fatal flush of red was absent.

"You are not fit to be out at this time of night," he said, harshly. "What are you doing up here?"

The boy looked at him, still retaining his hold, and standing in his path.

"I have come to speak to you, Jasper," he said, and his thin voice was strangely set and earnest.

Jasper looked down at him impatiently.

"Well," he said, roughly, "what is it? Couldn't you wait until I came in."

The boy shook his head.

"No," he said, and there was a strange light in his eyes, which never for a moment left the other's face. "I wanted to see you alone."

"Well, I am alone—or I wish I were," retorted Jasper, brutally. "What is it?" then he put his hand on the boy's shoulder and looked at him more closely. "Oh, I see!" he said, with a sneer. "You've been playing eavesdropper! Well," and he laughed cruelly, "listeners hear no good of themselves, though you heard no news."

A slight contraction of the thin lips was the only sign that the fell shaft had sped home.

"Yes," he said, calmly and sternly; "I have been eavesdropping; I have heard every word, Jasper."

[266]

Jasper nodded.

"Then you can indorse the truth of what I said, my dear Frank," and he smiled, evilly. "I have no doubt you have not forgotten your little escapade."

"I have not forgotten," was the response.

"Very good. Then I should advise you, if you care for your own safety and your cousin's welfare, to say nothing of the family honor, to advise her to come to terms—my terms. You have heard them, no doubt!"

"I have heard about them," said the boy. "I have—" he stopped a second to cough, but his hold on Jasper's sleeve did not relax even during the paroxysm—"I have heard them. I know what a devil you are, Jasper Adelstone. I have long guessed it, but I know now."

Jasper laughed.

"Thanks! and now you have discharged yourself of your venom, my young asp, we will go down. Take your hand from my coat, if you please."

"Wait," said the boy, and his voice seemed to have grown stronger; "I have not done yet. I have followed you here, Jasper, for a purpose; I have come to ask you for—for that paper."

Calmly and dispassionately the request was made, as if it were the most natural in the world. To say that Jasper was astonished does not describe his feelings.

"You—must be mad!" he exclaimed; then he laughed.

"You will not give it to me?" was the quiet demand.

Jasper laughed again.

"Do you know what that precious piece of hand-writing of yours cost me, my dear Frank? One hundred and fifty pounds that I shall never see again, unless your friend Holiday takes to paying his debts."

"I see," said the boy, slowly, and his voice grew reflective; "you bought it from him? No!"—with a sudden flash of inspiration—"he was a gentleman! By hook or by crook you stole it!"

Jasper nodded.

"Never mind how I got it, I have got it," and he struck his breast softly.

The sunken eyes followed the gesture, as if they would penetrate to the hidden paper itself.

"I know," he said, in a low voice; "I saw you put it there."

"And you will not see it again until I hand it to Stella, to-morrow, or give it to the magistrate before whom you will stand, my dear lad, charged with forgery."

The word had scarcely left his lips, but the boy was upon him, his long, thin arms—endued for a moment, as it seemed, with a madman's strength—encircling Jasper's neck. Not a word was uttered, but the thin, white face, lit up by the gleaming eyes, spoke volumes.

Jasper was staggered, not frightened, but simply surprised and infuriated.

"You—you young fool!" he hissed. "Take your arms off me."

[267]

"Give it to me! Give it to me!" panted the boy, in a frenzy. "Give it to me! The paper! The paper!" and his clutch tightened like a band of steel.

Jasper smothered an oath. The path was narrow; unconsciously, or intentionally, the frenzied lad had edged them both, while talking, to the brink, and Jasper was standing with his back to it. In an instant he realized his danger; yes, danger! For, absurd as it seemed, the grasp of the weak, dying boy could not be shaken off; there was danger.

"Frank!" he cried.

"Give it me!" broke in the wild cry, and he pressed closer.

With an awful imprecation, Jasper seized him and bore him backward, but as he did so his foot slipped, and the boy, falling upon him, thrust a hand into Jasper's breast and snatched the paper.

Jasper was on his feet in a moment, and flying at him tore the paper from his grasp. The boy uttered a wild cry of despair, crouched down for a moment, and then with that one wild prayer upon his lips: "Give it me!" hurled himself upon his foe. For quite a minute the struggle, so awful in its inequality, raged between them. His opponent's strength so amazed Jasper that he was lost to all sense of the place in which they stood; in his wild effort to shake the boy off he unconsciously approached the edge of the cliff. Unconsciously on his part, but the other noticed it, even in his frenzy, and suddenly, as if inspired, he shrieked out—

"Look! Leycester! He is there behind you!"

Jasper started and turned his head; the boy seized the moment, and the next the narrow platform on which they had stood was empty. A wild hoarse shriek rose up, and mingled with the dull roar of the waves beneath, and then all was still!

CHAPTER XL.Leycester had reached Carlyon on foot. He had left the house in the morning, simply saying that he was going for a walk, and that they were not to wait any meal for him. During the last few days he had wandered in this way, seemingly desirous of being alone, and showing no inclination toward even Charlie's society. Lady Wyndward half feared that the old black fits was coming on him; but Lenore displayed no anxiety; she even made excuses for him.

"When a man feels the last hour of his liberty approaching, he naturally likes to use his wings a little," she said, and the countess had smiled approvingly.

"My dear, you will make a model wife; just the wife that Leycester needs."

"I think so; I do, indeed," responded Lenore, with her frank, charming smile.

So Leycester was left alone to his own wild will during those last few days, while the dressmakers and upholsterers were hard at work preparing for "the" day.

He could not have told why he came to Carlyon. He did not[268] even know the name of the little village in which he found himself. With his handsome face rather grave and weary-looking, he had tramped into the inn, and sunk down into the seat which had supported many a generation of Carlyon fisherman and many sea-coast travelers.

"This is Carlyon, sir," said the landlord, in answer to Leycester's question, eying the tall figure in its knee breeches and shooting jacket. "Yes, sir, this is Carlyon; have you come from St. Michael's, sir?"

Leycester shook his head; he scarcely heard the old man.

"No," he answered; "but I have walked some distance," and he mentioned the place.

The old man stared.

"Phew! that's a long walk, sir; a main long walk. And what can I get you to eat, sir?"

Leycester smiled rather wearily. He had heard the question so often in his travels, and knew the results so perfectly.

"Anything you like," he said.

The

Comments (0)