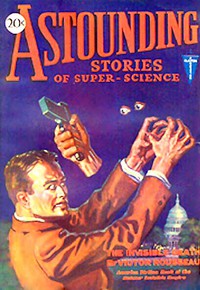

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930, Various [feel good books to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930, Various [feel good books to read .TXT] 📗». Author Various

"If he was an atheist and mocked at me it wouldn't be so bad," the good man declared. "I've had plenty of that kind. But he says he's not going to be hanged. He's mad, mad as a March hare. The Government has no right to send an insane man to the gallows."

"All bluff, my dear Mr. Wright," answered the Superintendent, when the chaplain voiced his protest. "He thinks he can get away with it. The commission has pronounced him sane, and he must pay the penalty of his crime."

By that mysterious process of telegraphy that exists in all penal institutions, Von Kettler's boast that he would beat the hangman had become the common information of the inmates. Bets were being laid, and the odds against Von Kettler ranged from ten to fifteen to one. It was generally agreed, however, that Von Kettler would die game to the last.

"You all ready, Mr. Squires?" the prowling Superintendent asked the hangman.

"Everything's O. K., sir."

The Superintendent glanced at the group of newspaper men gathered about the gallows. They, too, had heard of the prisoner's boast. One of them asked him a question. He silenced him with an angry look.

"The prisoner is in his cell, and will be led out in ten minutes. You shall see for yourselves how much truth there it in this absurdity," he said.

e looked at his watch. It lacked five minutes of eight. The preparations for an execution had been reduced almost to a formula. One minute in the cell, twenty seconds to the trap, forty seconds for the hangman to complete his arrangements: two minutes, and then the thud of the false floor.

Four minutes of eight. The little group had fallen silent. The hangman furtively took a drink from his hip-pocket flask. Three minutes! The Superintendent walked back to the[29] door of the death house and nodded to the guard.

"Bring him out quick!" he said.

The guard shot the bolt of Von Kettler's cell. The Superintendent saw him enter, heard a loud exclamation, and hurried to his side. One glance told him that the prisoner had made good his boast.

Von Kettler's cell was empty!

CHAPTER II Conferenceaptain Richard Rennell, of the U. S. Air Service, but temporarily detached to Intelligence, thought that Fredegonde Valmy had never looked so lovely as when he helped her out of the cockpit.

Her dark hair fell in disorder over her flushed cheeks, and her eyes were sparkling with pleasure.

"A thousand thanks, M'sieur Rennell," she said, in her low voice with its slight foreign intonation. "Never have I enjoyed a ride more than to-day. And I shall see you at Mrs. Wansleigh's ball to-night?"

"I hope so—if I'm not wanted at Headquarters," answered Dick, looking at the girl in undisguised admiration.

"Ah, that Headquarters of yours! It claims so much of your time!" she pouted. "But these are times when the Intelligence Service demands much of its men, is it not so?"

"Who told you I was attached to Intelligence?" demanded Dick bluntly.

She laughed mockingly. "Do you think that is not known all over Washington?" she asked. "It is strange that Intelligence should act like the—the ostrich, who buries his head in the sand and thinks that no one sees him because it is hidden."

Dick looked at the girl in perplexity. During the past month he had completely lost his head and heart over her, and he was trying to view her with the dispassionate judgment that his position demanded.

As the niece of the Slovakian Ambassador, Mademoiselle Valmy had the entry to Washington society. The Ambassador was away on leave, and she had appeared during his absence, but she had been accepted unquestionably at the Embassy, where she had taken up her quarters, explaining—as the Ambassador confirmed by cable—that she had sailed under a misconception as to the date of his leave.

runette, beautiful, charming, she had a score of hearts to play with, and yet Dick flattered himself that he stood first. Perhaps the others did too.

"Of course," the girl went on, "with the Invisible Emperor threatening organized society, you gentlemen find yourselves extremely busy. Well, let us hope that you locate him and bring him to book."

"Sometimes," said Dick slowly, "I almost think that you know something about the Invisible Emperor."

Again she laughed merrily. "Now, if you had said that my sympathies were with the Invisible Emperor, I might have been surprised into an acknowledgment," she answered. "After all, he does stand for that aristocracy that has disappeared from the modern world, does he not? For refinement of manners, for beauty of life, for all those things men used to prize."

"Likewise for the existence of the vast body of the nation in ignorance and poverty, in filth and squalor," answered Dick. "No, my sympathies are with law and order and democracy, and your Invisible Emperor and his crowd are simply a gang of thieves and hold-up men."

"Be careful!" A warning fire burned in the girl's eyes. "At least, it is known that the Emperor's ears are long."

"So are a jackass's," retorted Dick.

He was sorry next moment, for the girl received his answer in icy silence. In his car, which conveyed them from the tarmac to the Embassy, she received all his overtures in the same si[30]lence. A frigid little bow was her farewell to him, while Dick, struggling between resentment and humiliation, sat dumb and wretched at the wheel.

Yet the idea that Fredegonde Valmy had any knowledge of the conspiracy or its leaders never entered Dick's head. He was only miserable that he had offended her, and he would have done anything to have straightened out the trouble.

t seemed impossible that in the year 1940 the peace of the civilized world could be threatened by an international conspiracy bent on restoring absolutism, and yet each day showed more clearly the immense ramifications of the plot. Each day, too, brought home to the investigating governments more clearly the fact that the things they had discovered were few in number in comparison with those they had not.

The headquarters of the conspirators had never been discovered, and it was suspected that the powerful mind behind them was intentionally leading the investigators along false trails.

The conspiracy was world-wide. It had been behind the revolution that had recreated an absolutist monarchy in Spain. It had plunged Italy into civil war. It had thrown England into the convulsions of a succession of general strikes, using the communist movement as a cloak for its activities.

But nobody dreamed that America could become a fertile field for its insidious propaganda. Yet it was behind the millions of adherents of the so-called Freemen's Party, clamoring for the destruction of the constitution. Upon the anarchy that would follow the absolutist regime was to be erected.

Already the mysterious powers had struck. Departments of State had been entered and important papers abstracted. The Germania had mysteriously disappeared in mid-Atlantic, and a shipping panic had ensued. There were tales of mysterious figures materializing out of nothingness. It was known that the conspirators were in possession of certain chemical and electrical devices with which they hoped to achieve their ends.

The Superintendent of the penitentiary had had in his pocket an authorization to stop the execution of Von Kettler after he stood on the trap. Dead, he would be a mere mark of vengeance: alive, he might be persuaded to furnish some clue to the headquarters of the miscreants.

nd behind the conspirators loomed the unknown figure that signed itself the Invisible Emperor—in the communications that poured in to the White House and to the rulers of other nations. In the threats that were materializing with stunning swiftness.

Who was he? Rumor said that a former European ruler had not died as was supposed: that a coffin weighted with lead had been buried, and that he himself in his old age, had gone forth to a mad scheme of world conquest with a body of his nobles.

It had been practically a state of war since the shipment of gold, guarded by a detachment of police, had been stolen in broad daylight outside Baltimore, the police clubbed and killed by invisible assailants—as they claimed. The press was under censorship, troops under arms, and it was reported that the fleet was mobilizing.

In the midst of it all, Washington shopped, danced, feasted, flirted, like a swarm of may flies over a treacherous stream.

Intelligence was alert. As Dick started to drive away from the Slovakian Embassy, a man stepped quickly to the side of the car and thrust an envelope into his hand. Dick opened it quickly. He was wanted by Colonel Stopford at once, not at the camouflaged Headquarters at the War Department, but at the real Headquarters where no papers were kept but weighty decisions were made. And to that de[31]vious course the Government had already been driven.

Dick parked his car in a side street—it would have been under espionage in any of the official parking places—and set off at a smart walk toward his destination. Nobody would have guessed, from the appearance of the streets, that a national calamity was impending. The shopping crowds were swarming along the sidewalks, cars tailed each other through the streets; only a detachment of soldiers on the White House lawn lent a touch of the martial to the scene.

he building which Dick entered was an ordinary ten-story one in the business section; the various legal firms and commercial concerns that occupied it would have been greatly surprised to have known the identity of the Ira T. Graves, Importer, whose name appeared in modest letters upon the opaque glass door on the seventh story. Inside a flapper stenographer—actually one of the most trusted members of Intelligence's staff—asked Dick's name, which she knew perfectly well. Not a smile or a flicker of an eyelid betrayed the fact.

"Mr. Rennell," said Dick with equal gravity.

The girl passed into an inner room, and a buzzer sounded. In a few moments the girl came back.

"Mr. Graves will be here in a few minutes, Mr. Rennell, if you'll kindly wait in his office," she said.

Dick thanked her, and walked through into the empty office. He waited there till the girl had closed the door behind him, then went out by another door and found himself again in the corridor. Opposite him was a door with the words "Entrance 769" and a hand pointing down the corridor to where the Intelligence service had established another perfectly innocent front. Dick tapped lightly at this door, and a key turned in the lock.

The man who stepped quickly back was one of the heads of the Civil Service. The man at the flat-topped desk was Colonel Stopford. The man on a chair beside him was one of the heads of the police force.

he Colonel, a big, elderly man, dressed in a grey sack suit, checked Dick's commencing salutation. "Never mind etiquette, Rennell," he said. "Sit down. You've heard about the man Von Kettler's escape last night, of course?"

"Yes, sir."

"It's known, then. We can't keep things dark. He vanished from his cell in the death house, three minutes before the time appointed for his execution, though, as a matter of fact, he wasn't going to be hanged. Apparently he walked through the walls.

"There's a sequel to it, Rennell. It seems he had told the assistant-superintendent, a man named Anstruther, that he'd meet him at a restaurant in town that night. He promised to leave him a memento. Anstruther happened to remember this boast of Von Kettler's, and he surrounded the restaurant with armed detectives, on the chance that the fellow would show up. Rennell, Von Kettler was there!"

"He went to this restaurant, sir?"

"He walked in, just before the place was surrounded, engaged a table, and ordered a sumptuous meal. He told the waiter his name, said he expected a friend to join him, walked into the wash-room—and vanished! Two minutes later Anstruther and his men were on the job. Von Kettler never came out of the wash-room, so far as anybody knows.

"In the midst of the hue and cry somebody pointed to the table that Von Kettler had engaged. There was a twenty-dollar bill upon it, and a scrap of paper reading: 'I've kept my word. Von K.'"

Colonel Stopford looked at Dick fixedly. "Rennell, we may be fools," he said, "but we realize what we're up against. It's a big thing, and we're[32] going to need all our fighting grit to overcome

Comments (0)