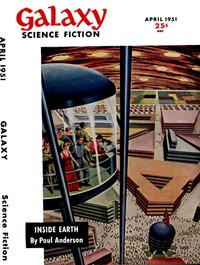

Inside Earth, Poul Anderson [10 ebook reader .TXT] 📗

- Author: Poul Anderson

Book online «Inside Earth, Poul Anderson [10 ebook reader .TXT] 📗». Author Poul Anderson

I had been ready for days now, postponing the moment. And those days were marching to the time of war, the rebels were quivering to go, a scant few weeks at most lay between me and the ruin of Valgolian plans and work and hope.

In my steadily expanding official capacity, I could go anywhere and do almost anything in an engineering line. So, bit by bit, I had tinkered with the base's general alarm system.

We had scoutships posted, of course, but by the very nature of things they had to be close to the planet or an approaching enemy would slip between them without detection. And the substantial vibrations of a ship traveling faster than light do not arrive much ahead of the ship itself. Whatever warning we had of a hypothetical assault would be very short. It would be signaled to all of us by a siren on the intercommunications system, and after that it would be battle stations, naval units to their ships and all others to such ground defenses as we had.

But modern warfare is all to the offense. There is no way of stopping an attack from space except by meeting it and annihilating it before it gets to its destination. The rebels were counting on that fact to aid them when they struck, but it would, of course, work against them if their enemy should happen to hit first. Everyone was understandably nervous about the chance of our being discovered and assailed.

Working a little at a time, I had put a special switch in the general alarm circuit. It showed up merely as one of many on a sector call board near my room; no one was likely to notice it. And my quarters were not those originally given me. I had moved to a smaller place farther from Barbara, ostensibly to be near my work at the shipyards, actually to be near the base's ultrabeam shack.

Now it was time to act.

I needed an excuse for not going to the gun turret where I was assigned. That involved faking a serious fever, but like all Intelligence men, I had been trained to full psychosomatic integration. The same neural forces that in hysteria produce paralysis, stigmata, and other real symptoms were under my conscious control. I thought myself sick. By morning I was half delirious and my veins were on fire.

The surgeon general came to see me. "What the hell's the trouble?" he wondered. "This place is supposed to be sterile."

"Maybe it's too damn sterile," I murmured with a perfectly genuine weakness. Then, fighting the light-headedness that hummed and buzzed in me: "Tsitbu fever, Doc. I'm sure that's what it is."

"Can't say I've ever heard of it."

"You'll find it in your medical books." He would, too. "It's found on the planet Sirius V, where I once visited. Filter-passing virus, transmitted by airborne spores. Not contagious here. In humans it becomes chronic; no ill effects except a few days' fever like this every few years. Now go 'way and lemme die in peace." I closed my eyes on the distorted and unreal world of sickness.

Later Barbara came in, pale and with her hair like a rumpled halo. I had to assure her many times that I was all right and would be on my feet in two or three days. Then she smiled and sat down on the bunk and passed a cool palm over my forehead.

"Poor Con," she said. "Poor squarehead."

"I feel fine as long as you're here," I whispered.

"Don't talk," she said. "Just go to sleep." She kissed me and sat quiet. Hers was the rare gift of being a definite personality even when silent and motionless. I clasped her hand and pretended to fall into uneasy sleep. After a while she kissed me again, very softly, and went out.

I told my body to recover. It took time, hours of time, while the stubborn cells retreated to a normal level of activity. I lay there thinking of many things, most of them unpleasant.

It was well into the night, the logical time to act even if the factories did go on a twenty-four hour basis.

I got up, still swaying a little with weakness, the dregs of the fever ringing in my head. After I had vomited and swallowed a stimulant tablet, I felt better. I put on my uniform, but substituted a plain service jacket without insignia of rank for the tunic. That should make me fairly inconspicuous in the confusion.

Strength came. I glanced cautiously along the dim-lit corridor, and it was empty and silent. I stole out and hurried toward the ultrabeam shack. My hidden switch was on the way; I threw it and ran on with lowered head.

The siren screamed behind me, before me, around me, the howling of all the devils in hell—Hoo! hoo! Battle stations! Strange ships approaching! Battle stations! All hands to battle stations! Hoo-oo!

I could imagine the pandemonium that erupted, men boiling out of factories and rooms, cursing and yelling and dashing frantically for their posts—children screaming in terror, women white-faced with sudden numbness—weapons manned, instruments sweeping the skies, spaceships roaring heavenward, incoherent yelling on the intercoms to find out who had given that signal. With luck, I would have fifteen minutes or half an hour of safe insanity.

A few men raced by me, on their way to the nearest missile rack. They paid me no heed, and I hurried along my own path.

The winding stair leading up to the ultrabeam shack loomed before me. I went its length, three steps at a time, bounding and gasping with my haste, up to the transmitter.

It was the tenuous link binding together a score of rebel planets, the only communication with the stars that glittered so coldly overhead. The ultrabeam does not have an infinite velocity, but it does have an unlimited speed, one depending solely on the frequency of the generating equipment, and since it only goes to such receivers as are tuned to its pattern—there must be at least one such tuned unit for the generator to work—it has a virtually infinite range. So men can talk between the stars, but are their words the wiser for that?

Up and up and up, round and round, up and up, metal clanging underfoot and always the demon screech of the siren—up!

I sprang from the head of the stairs and crossed the areaway in one leap to the open door of the shack. There was only one operator on duty, a slim boyish figure before the glittering panel. He didn't hear me as I came behind him. I knocked him out with a calculated blow to the base of the skull. He'd be unconscious for at least fifteen minutes and that was time enough. I heaved his body out of the chair and sat down.

The unit was set for the complicated secret scrambler pattern of the Legion, one which was changed periodically just in case. I twirled the dials, adjusting for the pattern of the set I knew was kept tuned for me at Vorka's headquarters.

The set hummed, warming up. I lifted my eyes and stared into the naked face of Boreas. The shack was above ground, itself dominated by the skeletal tower of the transmitter, and a broad port revealed land and sky.

Overhead the stars were glittering, bright and hard and cruel, flashing and flashing out of the crystal dark. The peaks rose on every side, soaring dizziness of cliffs and ragged snarl of crags, hemming us in with our tiny works and struggles. It was bitterly, ringingly cold out there; the snow screamed when you walked on it; the snapping thunder of frost-split rock woke the dull roar of avalanches, and there was the wind, the old immortal wind, moaning and blowing and wandering under the stars. I saw them running, little antlike men spilling from their nest and racing across the snow before they froze. I saw the ships rise one after the other and rush darkly skyward. The base had come alive and was reaching up to defy the haughty stars.

The set buzzed and whistled, warming up, muttering with the cosmic interference whose source nobody knows. I began to speak into the microphone, softly and urgently: "Calling Intelligence HQ, Sol III, North America Center. Captain Halgan Conru calling North America Center. Come in, Center, come in."

The receiver rustled with the thin dry voice of the stars. Dimly, I could hear the wind outside, snarling around the walls.

"Come in, Center. Come in, Center."

"Captain Halgan!" The voice rattled into the waiting stillness of the shack. "Captain Halgan, is it really you?"

"Get General Vorka at once," I said. "Meanwhile, are you recording? All right, be sure you get this."

I told them everything I knew. I told them what planet this was, and where we were on its surface, and what our strength and plans were. I gave them the disposition of the scoutship pickets, as far as those were known to me, and the standard Legion recognition signals. I finished with an account of the savage differences still existing between Earthman and Earthman, and Earth and its treacherous allies. And all the time I was talking to a recording machine. Nobody was listening.

When I was through, I waited a minute, not feeling any particular emotion. I was too tired. I sat there, listening to the wind and the interstellar whistling, till Vorka spoke to me.

"Halgan! Halgan, you've done it!"

"Shut up," I said. "What's coming now?"

"I checked the Fleet units. We have a Supernova with escort at Bramgar, about fifteen light-years from where you are. You are at their base, aren't you? Can you hold out for two days more?"

"I think so."

"Better get into the hills. We may have to bombard."

"Go to hell." I turned off the set.

Now to get back. They must already know it was a trick; they must be scouring the base for the saboteur. As soon as all loyal men were back, the hunt would really be on.

I had, of course, worn gloves. There would be no fingerprints. And the operator wouldn't know who had attacked him.

I changed the scrambler setting to one picked at random. And in a corner, as if it had fallen there by accident, I dropped a handkerchief stolen from Wergil of Luron. The tiny fragments of tissue which adhere to such a thing could easily be proven to be from him or one of his associates, for the basic Luronian life-molecules are all levo-rotatory. It might help.

I slipped back down the stairs, quickly and quietly. It was over. The base was as good as taken. But there was more to be done. Apart from the saving of my own life, there was still a desperate need for secrecy. For if the rebels knew what was coming, they might choose to stand and fight, or they might flee into the roadless wildernesses of space. Whichever it was, all our work and sacrifice would have gone for little.

The provocateur policy is the boldest and most farsighted enterprise ever undertaken. It is the first attempt to make history as we choose, to control the great social forces we are only dimly beginning to understand, so that intelligence may ultimately be its own master.

Sure. Very fine and idealistic, and no doubt fairly true as well. But there is death and treachery in it, loneliness and heartbreak, and the bitterness of the betrayed. Have we the right to set ourselves up as God? Can we really say, in our omniscience, that everyone but us is wrong? There were sane, decent, intelligent folk here on Boreas, the ones we needed so desperately for all civilization. Did we have to make them our enemies, so that their grandchildren might be our friends?

I didn't know. Wherever I turned, there were treason and injustice. However hard I tried to do right, I had to wrong somebody.

I ran on, back to my cabin. I peeled off my clothes and dived into bed, and by the time they looked in on me I had worked back most of my fever.

Don't think, Conru. Don't think of this new victory and the safety of the Empire. And, perhaps, a step closer to the harshly won unity of Earth. Don't think of the way the light catches in Barbara's hair and gets turned into molten gold. You've got a fever to create, man. You've got to think yourself sick again. That ought to be easy.

VIII

Barbara came in. She was white and still, and presently she leaned her head against my breast and cried quietly, for a long time.

"There is a spy here," she told me.

"I heard about it." I stroked her hair and held her to

Comments (0)