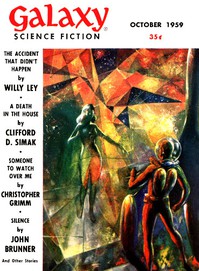

Someone to Watch Over Me, Floyd C. Gale and H. L. Gold [story books to read txt] 📗

- Author: Floyd C. Gale and H. L. Gold

Book online «Someone to Watch Over Me, Floyd C. Gale and H. L. Gold [story books to read txt] 📗». Author Floyd C. Gale and H. L. Gold

He decided there was no point bothering with the other planets; he might as well have his teeth and everything else taken care of on Earth, too. "Very wise of you," the kqyres approved. "The best is always the soundest, and, hence, most worth waiting for. Like Lyddy."

"Yes," Mattern agreed, "she is the best. And the most beautiful."

"Of course," the kqyres said. "Tell me more about her."

And Mattern talked, far into the night. What he couldn't remember of her by now, he imagined, so that the picture should be complete, not only for the xhind but for himself.

When his leg and his teeth had been fixed, "Why stop at that?" the kqyres asked. "If it had not been for the way that stepfather of yours treated you as a child—" for Len had found himself telling his companion not only about Lyddy but about everything—"you would be a fine-looking man today. It would be no difficult task to have you restored to what you should rightfully be."

Mattern would not, of course, do such a thing out of vanity. But the more presentable he made himself, the more he would be offering Lyddy. So it would be worth the extra time, especially since he could spend so much of it on Earth. Lyddy had come from Earth; it would be a bond between them later.

Doctors and cosmetologists got to work on him. Each treatment seemed to be lengthier than the preceding one, and more expensive. He could, however, easily afford it—all he had to do was make more trips. The kqyres not only told him what cargoes to take but advised him on the investments to make with his profits.

They did very well together. As far as Mattern was concerned, they did fabulously well, because he had to make enough on his side to counterbalance the entire expenses of a planet on the other. The thought impressed him. I am, in a sense, equal to the mbretersha, he thought, and she is a monarch. As a result, he walked a little more erect than even the operations had rendered him.

The dangers of his trade grew less and less frightening as he came to know his way between the universes, even though, at the same time, he began to realize how great those dangers were. He had not conceived of their immensity before. The reason there were asteroid belts in so many of the solar systems, he learned now, was that the xhindi had traded with other intelligent races in earlier eras, and there had been accidents. Those races were now extinct.

The xhindi themselves ceased to be monstrous in his eyes. He grew to accept their appearance as perfectly natural in their universe. Toward the kqyres, he came to feel something of what he had felt toward Schiemann, except that where Schiemann had looked up to him and relied on him, he found himself increasingly dependent on Njeri. He told him all his hopes and ambitions, and the kqyres listened attentively. Mattern tried to explain to him how he himself felt about Lyddy, and the kqyres tried to understand.

The kqyres taught Mattern how to play chess. "But that's our game!" Mattern said. "I mean we play it in our universe!"

"In ours also," the xhind smiled. "Who knows whether it came from our universe to yours, or yours to ours? Nor does it matter. It is an old game and a good one."

Mattern became increasingly skillful at it. He was pleased that there was an intellectual activity in which he could engage as an equal with the kqyres, and the kqyres seemed pleased, too.

When the treatments were over, Mattern looked in a mirror. He was straight; he was handsome. His skin was clear, his eyes bright. He looked less than his age. Now he could go back to Lyddy, assured that most women would find his physical appearance more than acceptable.

But he found himself hesitating. Only his physical appearance would be truly acceptable. There was something still lacking in him. His body was right, but the way he stood, the way he moved, the way he spoke, all these were wrong.

"I'm not finished yet," he said stumblingly to the kqyres, "not quite straightened out. I ought to be more—well, more smooth."

"You do lack polish," the kqyres admitted, "although you are far less awkward, shall we say, than when we first met."

"That's because of you, Njeri!" Mattern declared, with genuine gratitude. "You've taught me a lot!" And he looked at his outlandish friend with a great affection.

The kqyres seemed quite moved; he flickered like a pin-wheel. "You have been an exceedingly apt pupil, Mattern. When first I saw you, I did not think it possible that I should ever consider you a companion. However, I have found myself taking an increasing pleasure in your company. Sometimes I even forget you are a human."

Mattern could not speak; he was so overwhelmed by the tribute.

"The passage of time disclosed to me that there were sensitivities and perceptions beneath that—forgive me, but we know how misleading first impressions can be—boorish exterior. The very fact that you are conscious of your own deficiencies proves that you are more than the mere clod you still, on occasion, seem to be—"

"Can't I improve myself that way, too?" Mattern asked plaintively. "Can't I make myself worthy of Lyddy in every way?"

"Of course you can," the kqyres beamed. "Were you to apply yourself specifically to the acquisition of culture, I am sure you could become as polished as any human being can hope to be. But it will take time."

"Well," Mattern said, "Lyddy's waited so long, she can wait a little longer. Things worth having are worth waiting for."

Under Njeri's tutelage, Mattern cultivated the arts and the amenities. As he used his ship for a permanent residence, it was there that he housed his growing collection of costly rare objects of art, and his library, notable for its first editions—not only of tapes, but of books. His uniforms were cut by the best terrestrial tailors and he took kinescope courses in the liberal arts and social forms from the outstanding universities of Earth. The provincial twang vanished from his speech; he developed a taste for wine and conversation. Nobody, seeing him, could ever have fancied him once a poor wizened space rat.

As the years went by, he grew to become as much of a ruler in his way as the mbretersha in hers. She ruled one planet, he told himself, but he had a business empire farflung over many planets—all of which, to some extent, he did rule through his investments. He would have worlds to lay at Lyddy's feet now, he thought complacently. No man could offer any woman more.

The first Hesperian Queen didn't have a chance to last out his lifetime; he kept trading her in for another and yet another model, as better, faster, more luxurious starships were developed. Finally, he outbid the Federation Government itself for plans of the latest-model spacecraft. When the government protested, he graciously gave them copies free of all charge. "I merely wanted to be sure that I had the best ship available," he explained. "I have no objection to your having it also. But I knew that you could not afford to be as generous as I can."

He never had more than one ship, because it was too dangerous to run more than one cargo at a time. His crew was always as small in number as possible. He would have preferred none at all; actually, all spaceships could run themselves, for the controls were completely automatic. But regulations said there had to be a crew, both for the sake of "face"—many extraterrestrials couldn't seem to recognize the authority of machines—and because a power failure was not inconceivable.

So the Hesperian Queen carried four men. And, whenever she made the Jump through hyperspace, even the crew—though conditioned on Earth—was drugged. Mattern carried on alone. And if, when the crewmen awakened, they found that a day had passed when only an hour should have gone by, they knew better than to ask questions.

So the years went by—busy, pleasant, profitable years. The image of Lyddy was always before him, inspiring him to further efforts. Someday soon I will go back to her, he would tell himself. On his latest birthday, he looked in the mirror closely. At twenty-four, he had appeared forty; at forty, he could have passed for thirty. Sixteen years had gone by since that night with Lyddy. Now he was worthy of her or anyone.

"I think it's time I went back for her," he told the kqyres.

"For whom?" the kqyres asked; then added hastily, "Oh, yes, of course, Lyddy. We'll do that right after we come back from the Vega System. There's a little Earth-type planet out there—"

"Before we go to Vega," Mattern interrupted. "Now."

"But why the hurry? You've waited so long already—"

"I've waited too long. I'm not young any more."

"Neither is she," observed the kqyres. "Perhaps she is too old now, Mattern."

"She can't be too old," Mattern said. The tridi in his locker was Lyddy, and the picture was young; therefore, Lyddy must still be young.

"She may have married someone else. She may have numerous children clustering about her knee."

"Then I will take her away from her husband and children," Mattern declared. "Can you imagine that a little thing like that would stop me?"

"She may have lost her beauty," the kqyres said. "She may have left Hesperia. She may have suffered a disfiguring accident."

Mattern realized then that Njeri was deliberately trying to keep him from going back to Lyddy. Either he felt that she would interfere with the smooth operation of their business, or he was jealous of a third intruding into their company.

"I have done everything I did for the sake of winning Lyddy," Mattern said, biting off the words. "If all hope of her is gone, then my whole reason for working with you is gone. I will never go back to hyperspace."

"There are other women—"

"Not for me!"

"The business itself means nothing to you?" There was an aggrieved note in the kqyres' voice.

"It's just a living," Mattern said, "just a way of getting Lyddy. You know that was why I went into it. I thought you'd been listening to me all these years."

"I thought perhaps with the deepening of your interests—"

"They have only made me love her the more profoundly."

The kqyres took the equivalent of a deep breath. "You do not have a house or any regular place of residence. You cannot expect a lady to live permanently on a spaceship."

"I will build her a house."

"Will it not show her how carefully you have prepared for her if, first, you build her a palace worthy—"

"I have no time to build palaces."

"There is a tiny planet that circles the dim sun you call Van Maanen's star," the alien persisted. "It is always twilight there. The beings who live on that planet build crystal towers miles high and as fragile as spun glass, in dusk colors the rainbow never dreamed of."

"If she wants a crystal tower, I will have one built for her. But first I will ask her."

"Very well," the kqyres sighed, "since nothing else will satisfy you, let us return and fetch her."

And when they got to Erytheia City, Lyddy was still there, not only unmarried, but—in spite of all the years—unchanged.

VII

And now Mattern had been her husband for several months. He had begun to know her, and he realized that she could never be let known the truth about his life and his work. She would be frightened, and, if there was any emotion left over in her, angry.

He told the kqyres: "I've been thinking of taking Lyddy to Burdon. She might find distractions there that will take her mind off—things it shouldn't be on. What do you think of the idea?"

"I cannot tell," the kqyres replied doubtfully. "I have a curious feeling...."

"That what?" Mattern prompted him anxiously. It was the first time he had seen the kqyres definitely at a loss, although it had seemed to him of recent months that the xhind's assurance was beginning to ebb.

"... that I am getting too old for my work," the kqyres finished.

"Nonsense!" Mattern cried. The kqyres was his tower of strength; he would not conceive of any weakness in him. It would mean that he would be forced to rely upon himself. And yet, he thought, I am certainly old and experienced enough by now to begin relying upon myself. In fact,

Comments (0)