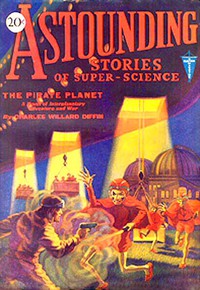

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930, Various [popular books of all time txt] 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930, Various [popular books of all time txt] 📗». Author Various

rofessor Sykes knew what it was to be harassed by the curious mob, to avoid traps set by ingenious reporters, but he knew, too, when he was meeting with honest bewilderment and a longing for knowledge. His fists were placed firmly on the hips of his stocky figure as he stood looking at the persistent questioner, and his eyes passed from the intent face to the snug khaki coat and the spread wings that proclaimed the wearer's work. A ship out of space—a projectile—this young man had said.

"Lieutenant," he suggested quietly—and again the smile had returned to his lips as he spoke—"sit down. I'm not as busy as I pretend to be. Now tell me: what in the devil have you got in your mind?"

And McGuire told him. "Like some of your dope," he said, "this is not for publication. But I have not been instructed to hush it up, and I know you will keep it to yourself."

He told the clear-eyed, listening man of the previous night's events. Of the radio's weird call and the mystery ship.

"Hallucination," suggested the scientist. "You saw the stars very clearly, and they suggested a ship."

"Tell that to Jim Burgess," said McGuire: "he was the pilot of that plane." And the scientist nodded as if the answer were what he expected.

He asked again about the ship's flight. And he, too, bore down heavily upon the matter of acceleration in the thin upper air. He rose to lay a friendly hand on McGuire's shoulder.

"We can't know what it means," he said, "but we can form our own theories, you and I—and anything is possible.

"It is getting late," he added, "and you have had a long drive. Come over[177] and eat; spend the night here. Perhaps you would like to have a look at our equipment—see Venus for yourself. I will be observing her through the sixty-inch refractor to-night. Would you care to?"

"Would I?" McGuire demanded with enthusiasm. "Say, that will be great!"

he sun was dropping toward the horizon when the two men again came out into the cool mountain air.

"Just time for a quick look around," suggested Professor Sykes, "if you are interested."

He took the lieutenant first to an enormous dome that bulged high above the ground, and admitted him to the dark interior. They climbed a stairway and came out into a room that held a skeleton frame of steel. "This is the big boy," said Professor Sykes, "the one hundred-inch reflector."

There were other workers there, one a man standing upon a raised platform beside the steel frame, who arranged big holders for photographic plates. The slotted ceiling opened as McGuire watched, and the whole structure swung slowly around. It was still, and the towering steel frame began to swing noiselessly when a man at a desk touched various controls. McGuire looked about him in bewilderment.

"Quite a shop," he admitted; "but where is the telescope?"

Professor Sykes pointed to the towering latticework of steel. "Right there," he said. "Like everyone else, you were expecting to see a big tube."

He explained in simple words the operation of the great instrument that brought in light rays from sources millions of light years away. He pointed out where the big mirror was placed—the one hundred-inch reflector—and he traced for the wondering man the pathway of light that finally converged upon a sensitized plate to catch and record what no eye had ever seen.

He checked the younger man's flow of questions and turned him back toward the stairs. "We will leave them to their work," he said; "they will be gathering light that has been traveling millions of years on its ways. But you and I have something a great deal nearer to study."

nother building held the big refractor, and it was a matter of only a few seconds and some cryptic instructions from Sykes until the eye-piece showed the image of the brilliant planet.

"The moon!" McGuire exclaimed in disappointed tones when the professor motioned him to see for himself. His eyes saw a familiar half-circle of light.

"Venus," the professor informed him. "It has phases like the moon. The planet is approaching; the sun's light strikes it from the side." But McGuire hardly heard. He was gazing with all his faculties centered upon that distant world, so near to him now.

"Venus," he whispered half aloud. Then to the professor: "It's all hazy. There are no markings—"

"Clouds," said the other. "The goddess is veiled; Venus is blanketed in clouds. What lies underneath we may never know, but we do know that of all the planets this is most like the earth; most probably is an inhabited world. Its size, its density, your weight if you were there—and the temperature under the sun's rays about double that of ours. Still, the cloud envelope would shield it."

McGuire was fascinated, and his thoughts raced wildly in speculation of what might be transpiring before his eyes. People, living in that tropical world; living and going through their daily routine under that cloud-filled sky where the sun was never seen. The margin of light that made the clear shape of a half-moon marked their daylight and dark; there was one small dot of light forming just beyond that margin. It penetrated the dark side. And it grew, as he watched, to a bright patch.

"What is that?" he inquired abstractedly—his thoughts were still filled with[178] those beings of his imagination. "There is a light that extends into the dark part. It is spreading—"

e found himself thrust roughly aside as Professor Sykes applied a more understanding eye to the instrument.

The professor whirled abruptly to his assistant. "Phone Professor Giles," he said sharply; "he is working on the reflector. Tell him to get a photograph of Venus at once; the cloud envelope is broken." He returned hurriedly to his observations. One hand sketched on a waiting pad.

"Markings!" he said exultantly. "If it would only hold!... There, it is closing ... gone...."

His hand was quiet now upon the paper, but where he had marked was a crude sketch of what might have been an island. It was "L" shaped; sharply bent.

"Whew!" breathed Professor Sykes and looked up for a moment. "Now that was interesting."

"You saw through?" asked McGuire eagerly. "Glimpsed the surface?—an island?"

The scientist's face relaxed. "Don't jump to conclusions," he told the aviator: "we are not ready to make a geography of Venus quite yet. But we shall know that mark if we ever see it again. I hardly think they had time to get a picture.

nd now there is only a matter of three hours for observation: I must watch every minute. Stay here if you wish. But," he added, "don't let your imagination run wild. Some eruption, perhaps, this we have seen—an ignition of gasses in the upper air—who knows? But don't connect this with your mysterious ship. If the ship is a menace, if it means war, that is your field of action, not mine. And you will be fighting with someone on Earth. It must be that some country has gained a big lead in aeronautics. Now I must get to work."

"I'll not wait," said McGuire. "I will start for the field; get there by daylight, if I can find my way down that road in the dark."

"Thanks a lot." He paused a moment before concluding slowly: "And in spite of what you say, Professor, I believe that we will have something to get together on again in this matter."

The scientist, he saw, had turned again to his instrument. McGuire picked his way carefully along the narrow path that led where he had parked his car. "Good scout, this Sykes!" he was thinking, and he stopped to look overhead in the quick-gathering dark at that laboratory of the heavens, where Sykes and his kind delved and probed, measured and weighed, and gathered painstakingly the messages from suns beyond counting, from universe out there in space that added their bit of enlightenment to the great story of the mystery of creation.

He was humbly aware of his own deep ignorance as he backed his car, slipped it into second, and began the long drive down the tortuous grade. He would have liked to talk more with Sykes. But he had no thought as he wound round the curves how soon that wish was to be gratified.

art way down the mountainside he again checked his car where he had stopped on the upward climb and reasoned with himself about his errand. Once more he looked out over the level ground below, a vast glowing expanse of electric lights now, that stretched to the ocean beyond. He was suddenly unthrilled by this man-made illumination, and he got out of his car to stare again at the blackness above and its myriad of stars that gathered and multiplied as he watched.

One brighter than the rest winked suddenly out. There was a constellation of twinkling lights that clustered nearby, and they too vanished. The eyes of the watcher strained themselves to see more clearly a dim-lit outline. There were no lights: it was a[179] black shape, lost in the blackness of the mountain sky, that was blocking out the stars. But it was a shape, and from near the horizon the pale gleams of the rising moon picked it out in softest of outline; a vague ghost of a curve that reflected a silvery contour to the watching eyes below.

There had been a wider space in the road that McGuire had passed; he backed carefully till he could swing his car and turn it to head once more at desperate speed toward the mountain top. And it was less than an hour since he had left when he was racing back along the narrow footpath to slam open the door where Professor Sykes looked up in amazement at his abrupt return.

The aviator's voice was hoarse with excitement as he shouted: "It's here—the ship! It's here! Where's your phone?—I must call the field! It's right overhead—descending slowly—no lights, but I saw it—I saw it!"

He was working with trembling fingers at the phone where Sykes had pointed. "Long distance!" he shouted. He gave a number to the operator. "Make it quick," he implored. "Quick!"

CHAPTER IIIack at Maricopa Flying Field the daily routine had been disturbed. There were conferences of officers, instructions from Colonel Boynton, and a curiosity-provoking lack of explanations. Only with Captain Blake did the colonel indulge in any discussion.

"We'll keep this under our hats," he said, "and out of the newspapers as long as we can. You can imagine what the yellow journals would do with a scarehead like that. Why, they would have us all wiped off the map and the country devastated by imaginary fleets in the first three paragraphs."

Blake regarded his superior gravely. "I feel somewhat the same way, myself. Colonel," he admitted. "When I think what this can mean—some other country so far ahead of us in air force that we are back in the dark ages—well, it doesn't look any too good to me if they mean trouble."

"We will meet it when it comes," said Colonel Boynton. "But, between ourselves, I am in the same state of mind.

"The whole occurrence is so damn mysterious. Washington hasn't a whisper of information of any such construction; the Secretary admitted that last night. It's a surprise, a complete surprise, to everyone.

"But, Blake, you get that new ship ready as quickly as you can. Prepare for an altitude test the same as we planned, but get into the air the first minute possible. She ought to show a better ceiling than anything we have here, and you may have to fly high to say 'Good morning' to that liner you saw. Put all the mechanics on it that can work to advantage. I think they have it pretty well along now."

"Engine's tested and installed, sir," was Blake's instant report. "I think I can take it up this afternoon."

e left immediately to hurry to the hangar where a new plane stood glistening in pristine freshness, and where hurrying mechanics grumbled under their breaths at the sudden rush for a ship that was expected to take the air a week later.

An altitude test under full load! Well, what of it? they demanded one of another; wouldn't another day do as well as this one? And they worked as they growled, worked with swift sureness and skill, and the final instruments took their place in the ship that she might

Comments (0)