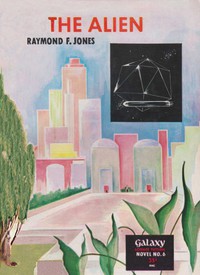

The Alien, Raymond F. Jones [free ebook reader for ipad TXT] 📗

- Author: Raymond F. Jones

Book online «The Alien, Raymond F. Jones [free ebook reader for ipad TXT] 📗». Author Raymond F. Jones

"Policy is controlled by the directors, who will be guided by your recommendations—"

Dreyer shook his head. "No, I think not, unless it pleases them. Should I ever recommend destruction of the alien, I would have to work through you. And that would take much convincing, would it not?"

"Plenty," said Underwood. "Are you recommending that now?"

"Not yet. No, not yet."

Slowly, Dreyer moved away toward the massive bath that housed the alien, Demarzule, Hetrarra of Sirenia, the Great One.

Underwood watching the beetle-back of the semanticist felt deflated by the encounter. Dreyer seemed always so nerve-rackingly calm. Underwood wondered if it were possible to acquire such immunity to turmoil.

He turned back to Terry, who had stood in silent agreement with Dreyer. "How are you and Phyfe coming along?"

"It's a slow business, even with the help of the key in the repository. That was apparently pure Stroid III, but we have two other languages or dialects that are quite different and we seem to have more specimens of those than we do of Stroid III. Phyfe thinks he's on the way to cracking both Stroid I and II, though. Personally, I'd like to get back out to the asteroids, if it weren't for Demarzule. I wasn't meant to be a scholar."

"Stick with it. I'm hoping that we can have some kind of idea what the Stroid civilization was like by the time Demarzule revives."

"How is it coming?"

"Cell formation is taking place, but how organs will ever develop is more than I can see. We're just waiting and observing. Four motion picture cameras are constantly at work, some through electron microscopes. At the end of six months we'll at least have a record of what occurred, regardless of what it is."

The mass of life grew and multiplied its millions of cells. Meanwhile, another growth, less tangible but no less real, was swiftly rising and spreading through the Earth. The mind of each man it encompassed was one of its cells, and they were multiplying no less rapidly than those of the growth within the marble museum building. The leadership of men by men had proven false beyond all hope of ever restoring the dream of a mortal man who could raise his fellows to the heights of the stars. But the Great One was something else again. Utterly beyond all Earthly build and untainted with the flaws of Earthmen, he was the gift of the gods to man—he was a god who would lift man to the eternal heights of which he had dreamed.

The flame spread and leaped the oceans of Earth. It swept up all creeds and races and colors.

Delmar Underwood looked up from his desk in annoyance as a pompous, red-faced man of short, stout build was ushered in by his secretary. The man halted halfway between the door and the desk and bowed slightly.

He said, "I address the Prophet Underwood by special commission of the Disciples."

"What the devil—?" Underwood frowned and extended a hand toward a button. But he didn't ring. The visitor extended an envelope.

"And by special authorization of Director Boarder of the Institute!"

Still keeping his eyes on the man, Underwood accepted the envelope and ripped it open. In formal language and the customary red tape manner, it instructed Underwood to hear the visitor, one William B. Hennessey, and grant the request that Hennessey would make.

Underwood knew him now. His throat felt suddenly dry. "What's this all about?"

The man shrugged disparagingly. "I am only a poor Disciple of the Great One, who has been commissioned by his fellows to seek a favor at the hands of the Prophet Underwood."

As Underwood looked into the man's eyes, he felt a chill, and a wave of apprehension swept over him with staggering force.

"Sit down," he said. "What is it you want?" He wished Dreyer were here to place some semantic evaluation upon this crazy incident.

"The Disciples of the Great One would have the privilege of viewing the Master," said Hennessey as he sat down near the desk. "You scientists are instruments selected for a great task. The Great One did not come only to a select few. He came to all mankind. We request the right to visit the temple quietly and view the magnificent work you are doing as you restore our Master to life so that we may receive of his great gifts."

Underwood could picture the laboratory filled with bowing, praying, yelling, fanatic worshippers crowding around, destroying equipment and probably trying to walk off with bits of holy protoplasm. He pressed a switch and spun a dial savagely. In a moment the face of Director Boarder was on the tiny screen before him.

"This fanatic Hennessey is here. I just wanted to check on the possible liability before having him thrown out on his ear."

Boarder's face grew frantic. "Don't do that! You got my note? Do exactly as I said. Those are orders!"

"But we can't carry on an experiment with a bunch of fanatics yapping at our heels."

"I don't care how you do it. You've got to give them what they want. Either that or fold up the experiment. The latest semi-weekly poll shows they effectively control eighty million votes. You know what that means. One word to the Congressional scientific committee and all of us would be out on our ear."

"We could shut the thing up and call it off. The protoplasm would just quietly die and then what would these birds have to worship?"

"Destruction of government property can carry the death penalty," said Boarder ominously. "Besides, you're too much of the scientist to do that. You want to see the thing through just as much as the rest of us do. If I had the slightest fear that you'd destroy it, I'd yank you out of there before you knew where you were—but I haven't any such fears."

"Yes, you're right, but these—" Underwood made a grimace as if he were trying to swallow an oyster with fur on.

"I know. We've got to put up with it. The scientist who survives in this day and age is the one who adjusts to his environment." Boarder grinned sourly.

"I went out to space to escape the environment. Now I'm right back in it, only worse than ever."

"Well, look, Underwood, why can't you just build a sort of balcony with a ramp running across the lab so that these Disciples of the Great One can look down into the bath? You could feed them in at one end of the building and run them out the other. That way it wouldn't upset you. After all, it's only going to last six months."

"When the Stroid revives, they'll probably want to put him on a throne with a radiant halo about his head." Boarder laughed. "If he represents the civilization whose artifacts we've found on the asteroids, I think he'll take care of his 'Disciples' in short order. Anyway, you'll have to do as they demand. It won't last long."

Boarder cut off and Underwood turned back to the bland Hennessey, who sat as if nothing would ever disturb him.

"You see," Hennessey said, "I knew what the outcome would be. I had faith in the Great One."

"Faith! You knew that the scientific committee would back you up because you represent eighty million neurotic crackpots. What will you do when your Great One wakes up and tells you all to go to hell?"

Hennessey smiled quietly. "He won't. I have faith."

CHAPTER SIXTwo days later, Underwood received a call from Phyfe, asking for an appointment. It was urgent; that was all Phyfe would tell him.

The archeologist had not heard of the demands of the Disciples. He was surprised to see the construction under way in the great central hall where the restoration equipment was installed.

He found Underwood with Illia in the laboratory examining films of the protoplasmic growth.

"What are you building out there?" he asked. "I thought you had all the equipment in."

"A monument to human stupidity," Underwood growled. Then he told Phyfe of the orders he had received. "We're putting in a balcony so that the faithful can look down upon their Great One. Boarder says we'll have to put up with this nonsense for six months."

"Why six months?"

"Demarzule will be revived by then or else we'll have failed. In either case, the Disciples will have come to an end."

"Why?"

Underwood glanced up in irritation. "If he's dead, they won't have anything to worship. And if he lives, he certainly won't have anything to do with them."

"I could ask another 'why,'" said Phyfe, "but I'll put it this way. You know nothing of how he will act if he lives. And if he dies he'll probably be a martyr that will establish a new worldwide religion—with those of us who have had to do with this experiment and its failure being burned at the stake."

Underwood laid down the sheaf of films. Out among the asteroids he had learned to respect the old archeologist's opinions but Dreyer had already laid more of a burden upon him than he felt he should bear.

"The technological aspects of this problem are more than you say you have found?"

"Fortunately for us, certain Stroid records were small metallic plates whose molecular structure was altered according to script or vocal patterns. Some of the boys in the lab have developed a device for listening to the audio records. We have actually heard the voices of the Stroids! At least there are sounds that resemble a spoken language. But it is what we have found on the written records that brought me here.

"More than eighty-five years ago, the most fortunate find previous to the discovery of the repository was made. An extensive cache of historical records was uncovered by Dickens, one of the early workers in the field. They were almost fused together, and the molecular alteration was barely traceable due to exposure to terrific heat. But we've succeeded in separating the plates and transferring their records in amplified form to new sheets. And we can read them. We have a remarkably complete section of Stroid history just before their extermination, and, if we are reading it correctly, there's a surprising fact about them."

"What is that?"

"They were not native to this Solar System. They were extra-galactic refugees whose home world had been destroyed in something completely revolting in an intellect that would foresee the doom of a world and set about to assure its own preservation."

"But that is only your own subjective extension," Illia answered. "There is no such semantic concept in the idea."

"Isn't there? The egotism, the absolute lack of concern for a creature's fellows—those are semantically contained in it. And that is why I'm more than a little afraid of what we shall find if we do succeed in reviving this creature. How is it developing?"

"It seems to be going through a sort of conventional embryonic growth," Illia answered. "It's already passed a pseudo-blastic stage. So far, it has generally mammalian characteristics; more than that is impossible to say. But what about this new evidence enough for my mental capacity. I can't and won't give a damn about any other aspects."

"You must!" Phyfe's eyes were suddenly afire, demanding, unyielding. "We have new evidence—Terry may have been right when he asked to have the protoplasm destroyed."

Illia froze. "What evidence?"

"What type of mentality would attempt to preserve itself through a planetary catastrophe that destroyed all its contemporaries?" asked Phyfe. "I find some great interstellar conflict and whose enemies eventually traced them and destroyed for the second time the world on which they lived. Out of all that ancient people, destroyed as completely as was Carthage, only this single individual remained.

"Do you see the significance of that? If he lives, he will live again with the same war-born hate and lust for revenge that filled him as he saw his own world fall!"

"It won't survive the knowledge that all that he fought for disappeared geologic ages past," objected Underwood. "Besides, you are contradicting yourself. If he was so unconcerned about his own world, perhaps he had no interest in the conflict. Maybe he was the supreme genius of his day and wanted only to escape from a useless carnage that he could not stop."

"No, there is no contradiction," said Phyfe earnestly. "That is typical of the war leader who has brought his people to destruction. At the moment when disaster overwhelms them, he thinks only of himself. The specimen we have here is a supreme example of what such egocentric desires for self-preservation lead to."

Phyfe abruptly rose from the chair and tossed a sheaf of papers on the laboratory bench. "Here it is. Read it for yourself. It's a pretty free translation of the story we found on Dickens' records."

He left abruptly. Illia and Underwood turned to the short script he had left behind and began reading.

The

Comments (0)