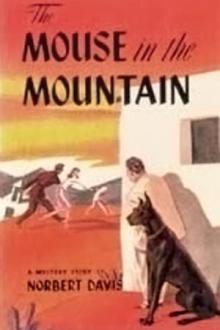

The Mouse in the Mountain, Norbert Davis [the beginning after the end read novel TXT] 📗

- Author: Norbert Davis

- Performer: -

Book online «The Mouse in the Mountain, Norbert Davis [the beginning after the end read novel TXT] 📗». Author Norbert Davis

“I’ve got it. I’ll pay you. Why, I wouldn’t double-cross you, Doan!”

“Not twice,” Doan agreed. “What about Concha?”

“Oh, her. She stays here, of course.”

“After all that song and dance about Hollywood and a house with an inside toilet?”

Eldridge shrugged. “You know how a guy talks to a dame. I was only fooling. What would I want with a little stupe like her? Once I contact Bumpy I’ll get something really fancy. Colonel Callao can have Concha back.”

“I have an idea,” Doan said, “that when Colonel Callao finds out he’s going to get Concha back, we’re going to have more trouble with him than we do with Bautiste Bonofile.”

“Callao’s a dope, like I said. And besides that, he’s ignorant.”

“I hope so,” said Doan. He stood up. “Well, I’m going to find Perona now and tell him you and I have come to an agreement, and after that we can arrange—”

The tiles moved slightly under his feet. It was just a slight shudder back and forth that made his knees feel queerly stiff and numb. Carstairs got up very quickly.

“That’s just an earth tremor,” said Eldridge. “We have them all the time here. There’s a fault through this range. We never have a serious one—not what you’d call an earthquake or anything like that.”

The tiles moved in a quick little jerk. Carstairs barked angrily at Doan.

“Shut up, you fool,” Doan told him. “I’m not responsible for this.”

The tiles rippled. There was no other word for it. It was as though someone had stirred their hard surface with a spoon, and they cracked and crumbled and split. Doan went staggering, and dust came up hot and acrid into his nostrils. Carstairs sneezed indignantly.

There was a long, ominous rumble that was like thunder but more terrible and spine-chilling, and the earth began to move back and forth slowly and relentlessly. Doan went headlong. Carstairs scrambled desperately for his balance, slipped and fell hard on tiles that were slick from the water that had been in the fountain.

The dust was a thick veil, and through it things clumped and banged and groaned weirdly. The patio mall moved and hovered over Doan, and before he could get up it moved back again reluctantly, back and back at an impossible angle, and then it crumbled away and hit the ground, and dust rose from it in a yellow, rolling puff like a smoke signal. The noise of its fall was lost in the greater jarring rumble that came from everywhere.

The seconds dragged like hollow centuries. Doan got up, and the ground moved out from under him, and he went down again. Carstairs clawed frantically, breathing in short, hard snarls, trying to get his feet under him. The ground stopped jerking, and quivered like jelly and then quieted.

Doan sat up and looked across the patio. Eldridge was still sitting in his chair against the house wall. His eyes were bulged wide, and he moved his lips stiffly. Everything was suddenly deathly still.

Very slowly, as if it were tired now, the earth moved up and then dropped back again. In the house, timbers screamed like agonized things, and then the roof sagged a little and started to slide.

Doan’s throat was tight. “Eldridge! Look out!”

Eldridge tried to move, tried to fight out of his chair, and then a solid waterfall of plaster and tile and broken adobe poured down over him.

Doan got up and scrambled toward the pile of debris. It had knocked Eldridge forward and down. Doan heaved at a broken timber, threw it sideways, pulled out another. He clawed tile and thick chunks of adobe right and left behind him, and then he saw Eldridge’s head and shoulders, queerly flattened and deflated, gray with plaster dust.

Doan dug his hands under Eldridge’s armpits and hauled back. A tile fell off the roof and tucked into the ground beside him, and the top of the house wall crumbled slightly. Doan heaved again, and then Eldridge was free. Doan dragged him toward the empty space at the side of the patio where the wall had fallen outward.

Eldridge was limp and unmoving, but he was breathing in short, choked gasps. His legs and lower body were twisted grotesquely askew.

Doan took his handkerchief from his coat pocket and dampened it in the water that was left in the fountain. He wiped the layer of plaster dust from Eldridge’s face and saw that there was a thin trickle of bright, arterial blood coming out of the corner of Eldridge’s mouth.

Eldridge opened his eyes. “Why, Doan,” he said in a faint, surprised voice.

“Take it easy,” said Doan.

“Why, what’re you looking at me that way for, Doan? I ain’t hurt. I can’t feel—Doan!”

“Take it easy,” said Doan. “Don’t try to move.”

“Doan! My legs won’t—Doan! Something’s wrong with me! Don’t stand there! Get a doctor!”

“A doctor won’t do you any good.”

“Doan! I’m not—I’m not—”

“Yes,” said Doan.

Eldridge’s face was purple-red, and his throat bulged with his straining effort to hold up his head.

“No! I won’t—I can’t—Bumpy… governor whole state… No! Doan! You’re lying,, damn you!”

“Your back’s broken,” said Doan. “And you’re all scrambled up inside.”

Eldridge’s breath bubbled and sputtered in his throat. His lips pulled back and showed the blood on his teeth, and he said thickly but very clearly:

“God damn you to hell.”

His head rolled limply to one side. Doan stood up lowly. He looked at the wadded, damp handkerchief in his hand and then dropped it with a little distasteful grimace.

From behind him a voice said: “You will stand still, if you please.”

Doan didn’t move, but he looked at Carstairs murderously. Carstairs was involved in a complicated exercise that would enable him to lick one hind paw. His legs were sprawled out eccentrically in all directions, and he stared back at Doan with an expression of sheepish apology.

“You brainless, incompetent giraffe,” said Doan.

“Do not blame your dog for not warning you,” aid the voice behind him. “I was downwind, and I can move so very quietly sometimes. Please do stand still.”

Doan didn’t move his arms or legs or body or head, but he flicked his eyes to the left, then looked at Carstairs, and then flicked them to the left again. Carstairs got up instantly and began to sidle to his own right.

“No,” said the voice. “I would not like to kill your dog. Stop him.”

Doan nodded once. Carstairs sat down, watching him.

“No,” said the voice.

Doan nodded again. Carstairs slid his forelegs out slowly and sprawled on the broken tiles.

“That is so much better,” said the voice. “Your dog is beautifully trained. It would be a shame if he were hurt. I think you have a gun. Do not try to use it. Keep your hands away from your body and turn around slowly.”

Doan turned around. The voice belonged to a thin, elderly man who looked very neat and well-tailored in a gray tweed suit. He had a long nose and a shapeless, bulging mustache, and he wore thick glasses that distorted his watery blue eyes. He had no gun, but he was holding a rolled green umbrella under his right arm, and Doan was not so foolish as to think it was actually only an umbrella.

“What is your name?”

“Doan,” said Doan. “What’s yours?”

“I am Lepicik. Were you robbing that man?”

“I hadn’t gotten around to it yet.”

“Did you kill him?”

“No,” said Doan. “The earthquake did. We just had one, or didn’t you notice?”

“Yes,” said Lepicik pleasantly. “It was quite violent, wasn’t it? From where did you come here?”

“From the Hotel Azteca in Mazalar.”

“You have been staying there?”

“For a couple of days.”

“How did you come here to Los Altos? By what means of travel?”

“On a sightseeing bus.”

“Who came with you?”

“Why?” Doan asked.

Lepicik moved the umbrella slightly. “You would really be so much wiser to answer my questions.”

“Okay,” said Doan. “An heiress by the name of Patricia Van Osdel and her maid, name of Maria, and her gigolo, name of Greg. A man named Henshaw and his wife and kid. A schoolteacher by the name of Janet Martin.”

“Thank you,” said Lepicik. “Thank you so very much. Good day.”

“Good day,” said Doan.

Lepicik walked backwards away from him. He didn’t hesitate or feel his way. He walked as confidently as though he had eyes in the back of his head. He disappeared around the edge of the broken patio wall.

Doan leaned over and picked up a chunk of adobe and hurled it at Carstairs. Carstairs jumped up nimbly and let the adobe skid harmlessly under him.

“What do you think I drag you around for?” Doan demanded angrily. “Keep your eyes open after this.”

Carstairs looked even more apologetic than he had at first. He moved back and forth in tight, uneasy steps, lowering his head.

“All right,” said Doan. “Come on, and we’ll see if there’s anyone else left alive in this town.”

WHEN DOAN LEFT THEM AT the corner, Janet and Captain Perona stood still for a moment watching him trudge up the slope toward the Avenida Revolucion with Carstairs wandering along ahead of him.

“Why did you say that to him?” Janet demanded.

“I beg pardon?” said Captain Perona.

“Why did you warn him about torturing and beating Eldridge? That’s perfect nonsense.”

“I think not,” Captain Perona denied.

“Mr. Doan is a very mild, polite, pleasant person. He would no more torture anyone than I would.”

“Oh, yes,” said Captain Perona. “We have his record, you see. He is what you call a private detective. Very successful. His record is full of violence. He does not care at all what he does to solve a case. But he never quite gets caught breaking the law. He is very clever and very lucky.”

“Clever!” Janet echoed incredulously. “Mr. Doan? Why—why, he’s the most talkative, open, naive, boyish—”

“Oh, no,” said Captain Perona positively. “That is also in his record. He fools people with his innocent manner, but he is not innocent in the slightest. Assuredly not.”

“I think you’re just making this up.”

“Senorita,” said Captain Perona, “I do not make things up, if you please.”

“Well, you’re mistaken, then.”

“And I do not make mistakes.”

“Not ever?” Janet asked in an awed tone.

“No. I am—” Captain Perona stopped short, staring narrowly at her. “So you are mocking me!”

“Yes,” said Janet.

Captain Perona breathed hard. “I will forgive you—this time, senorita. Mocking people and ridiculing them is, I understand, a custom in your detestable country.”

“My what?” Janet said, stung.

“The United States. I have heard that its people are very ignorant and uncouth.”

“They are not!”

“Especially the women. They have loud, shrill voices, and they shout in public.”

“They do not!” Janet cried.

Captain Perano smiled at her blandly. Several passersby turned to look curiously at her. She began to blush, and she put her hand up to her lips. “You see?” asked Captain Perona. “Even you do it. Shouting in public is considered very unmannerly in Mexico.”

Janet said in a choked whisper: “You said those things just to make me mad so I’d raise my voice and—and make myself look foolish!”

“That is correct,” said Captain Perona. “And you did. Very foolish.”

“Please go away and leave me alone.”

“No,” said Captain Perona.

Janet turned around and started blindly across the marketplace. After three steps she staggered just a little, groping for her balance, and then Captain Perona’s hand was under her arm, supporting her.

“You are ill, senorita?” he asked. There was no mockery in his voice now.

Janet said: “If—if I could just

Comments (0)