All About Coffee, William H. Ukers [short story to read .txt] 📗

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Book online «All About Coffee, William H. Ukers [short story to read .txt] 📗». Author William H. Ukers

As a result of our experiments with different ways of roasting and brewing coffee, we have found the following plan to be the most convenient and the best: the coffee will taste the same every time and it will taste good. If a good berry be properly roasted and the infusion be of the proper strength, good coffee must result. A Mocha berry should be selected and roasted seven or eight pounds at a time in a cylindrical drum. After roasting it should be placed in a stone jar with a mouth three inches in diameter. The jar should be closed air-tight. This will furnish two cups of coffee daily for six months. A quart should be taken from the jar at a time and ground. The ground coffee should be kept in covered glass jars.

The best coffee pot was found to be the common biggin having an upper compartment with a perforated bottom upon which to place the coffee. To make one cup of this infusion, place half an ounce of ground coffee in the upper compartment and six fluid ounces of water into the bottom. Put the biggin over a gas lamp. After three minutes the water will boil. When steam appears, take the biggin from the fire and pour the water into a cup and thence immediately into the top of the biggin where it will extract the berry by replacement. (Here follows an experiment.)

This experiment shows that loss of weight is no criterion that coffee is properly roasted, neither is the color (by itself) nor the temperature, nor the time.

Next we experimented to ascertain whether the aroma developed by roasting coffee and which is lost might not be collected and added to the coffee at pleasure. An attempt was made to drive the volatile oils from roasted coffee by steam and make a dried extract of the residual coffee to which the oils were to be later added. Two attempts were made and both failed. It appears that but a small quantity of the aroma is lost in roasting and that is mixed with bad smelling vapors from which it is impossible to free it.

Then we tried to make a potable coffee by making an aqueous extract of raw coffee, evaporating to dryness and roasting the residue. (Here follows the experiment.)

This also was unsuccessful. The great trouble here is a dark shiny residue, which, while tasteless, is very disagreeable to look at. In the preparation of coffee by boiling, two and a half times as much matter is extracted as by biggin.

The proper method of roasting coffee is as follows: It should be placed in a cylinder and turned constantly over a bright fire. When white smoke begins to appear, the contents should be closely watched. Keep testing the grains. As soon as a grain breaks easily at a slight blow, at which time the color will be a light chestnut brown, the coffee is done. Cool it by lifting some up and dropping it back with a tin cup. If it be left to cool in a heap there is great danger of over-roasting. Keep the coffee only in air-tight vessels. Measure the infusions, a half ounce of coffee to six ounces of water per cup.

All "extracts of coffee" are worthless. Most of them are composed of burned sugar, chicory, carrots, etc.

In 1883, an authority of that day, Francis B. Thurber, in his book, Coffee; from Plantation to Cup, which he dedicated to the railroad restaurant man at Poughkeepsie, because he served an "ideal cup of coffee", came out strongly for the good old boiling method with eggs, shells included. This was the Thurber recipe:

Grind moderately fine a large cup or small bowl of coffee; break into it one egg with shell; mix well, adding enough cold water to thoroughly wet the grounds; upon this pour one pint of boiling water: let it boil slowly for ten to fifteen minutes, according to the variety of coffee used and the fineness to which it is ground. Let it stand three minutes to settle, then pour through a fine wire-sieve into a warm coffee pot; this will make enough for four persons. At table, first put the sugar into the cup, then fill half-full of boiling milk, add your coffee, and you have a delicious beverage that will be a revelation to many poor mortals who have an indistinct remembrance of, and an intense longing for, an ideal cup of coffee. If cream can be procured so much the better, and in that case boiling water can be added either in the pot or cup to make up for the space occupied by the milk as above; or condensed milk will be found a good substitute for cream.

In 1886, however, Jabez Burns, who knew something about the practical making of the beverage as well as the roasting and grinding operations, said:

Have boiling water handy. Take a clean dry pot and put in the ground coffee. Place on fire to warm pot and coffee. Pour on sufficient boiling water, not more than two-thirds full. As soon as the water boils add a little cold water and remove from fire. To extract the greatest virtue of coffee grind it fine and pour scalding water over it.

John Cotton Dana, of the Newark Public Library, says he remembers how in his old home in Woodstock, Vt., they had always, in the attic, a big stone jar of green coffee. This was sacred to the great feast days, Thanksgiving, Christmas, etc. Just before those anniversaries, the jar was brought forward and the proper amount of coffee was taken out and roasted in a flat sheet-iron pan on the top of the stove, being stirred constantly and watched with great care. "As my memory seems to say that this was not constantly done," says Mr. Dana, "it would seem that, even then, my father, who kept the general store in the village, bought roasted coffee in Boston or New York."

At the close of the century, there were still many advocates of boiling coffee; but although the coffee trade was not quite ready to declare its absolute independence in this direction, there were many leaders who boldly proclaimed their freedom from the old prejudice. Arthur Gray, in his Over the Black Coffee, as late as 1902, quoted "the largest coffee importing house in the United States" as advocating the use of eggs and egg-shells and boiling the mixture for ten minutes.

Latest Developments in Better Coffee Making

Better coffee making by co-operative trade effort got its initial stimulus at the 1912 convention of the National Coffee Roasters Association. As a result of discussions at that meeting and thereafter, a Better Coffee Making Committee was created for investigation and research.

The coffee trade's declaration of independence in the matter of boiled coffee was made at the 1913 convention of the National Coffee Roasters Association, when, after hearing the report of the Better Coffee Making Committee, presented by Edward Aborn of New York, it adopted a resolution saying that the recommendations met with its approval and ordering that they be printed and circulated.

The work done by the committee included "the first chemical analysis of brewed coffee on record", a study of grindings, and a comparison of the results of four brewing methods. Its conclusions and recommendations were embodied in a booklet published by the National Coffee Roasters Association, entitled From Tree to Cup with Coffee, and were as follows:

Roasting

The Roaster or "Coffee Chef" is the only cook necessary to a good cup of coffee. He sends it to the consumer a completely cooked product.

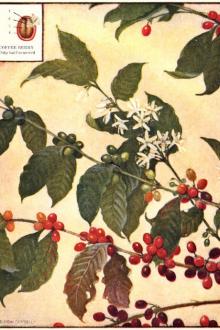

In the roasting process the berries swell up by the liberation of gases within their substance. The aromatic oils contained in the cells are sufficiently developed or "cooked", and made ready for instantaneous solution with boiling water, when the cells are thoroughly opened by grinding.

The roasting principles of different green coffees vary. Trained study and a nice science in timing the roast and manipulating the fire is necessary to a perfect development of aroma and flavor.

The drinking quality is largely dependent upon the experienced knowledge of the coffee roaster and his scientific methods and modern machinery, by which the coffee is not only roasted, but cleaned, milled and completely manufactured to a high point of perfection.

In their National Association work, the wholesale roasters are giving the public new facts and valuable information, from scientific researches, investigations, etc.

Grinding. The roasted berry is constructed of fibrous tissues formed into tiny cells visible only under the microscope, which are the "packages" wherein are stored the whole value of coffee, the aromatic oils. Like cutting open an orange, the grinding of coffee is the opening of surrounding tissue and pulp, and the finer it is cut the more easily are the "juices" released.

The fibrous tissue itself is waste material, yielding, by boiling or too long percolations, a coffee colored liquid which is fibrous and twangy in taste, has no aromatic character, and contains undesirable elements.

The true strength and flavor of roasted coffee is ground out, not boiled out. The finer coffee is ground, the more thoroughly are the cells opened, the surfaces multiplied, and the aromatic oils made ready for separation from their husks. Hence it follows that:

Coarse ground coffee is unopened coffee—coffee thrown away.

The finer the grind, the better and greater the yield. With pulverized coffee (fine as corn meal) the fully released aromatic oils are instantaneously soluble with boiling water.

In ground coffee the oils are standing in "open packages," escaping into the air and absorbing moisture, etc., necessitating quick use or confinement in air proof and moisture proof protection.

Brewing. From scientific researches by the National Coffee Roasters' Association, including the first chemical analysis on record of brewed coffee, produced by various brewing methods, the fundamental principles of coffee making have been clearly established. These principles are simple, and when once understood equip any person to intelligently judge the merits and defects of the various coffee making devices on the market. They constitute the law of coffee brewing, and may be stated as follows:

Correct brewing is not "cooking." It is a process of extraction of the already cooked aromatic oils from the surrounding fibrous tissue, which has no drinkable value. Boiling or stewing cooks in the fibre, which should be wholly discarded as dregs, and damages the flavor and purity of the liquid. Boiling coffee and water together is ruin and waste.

The aromatic oils, constituting the whole true flavor, are extracted instantly by boiling water when the cells are thoroughly opened by fine grinding. The undesirable elements, being less quickly soluble, are left in the grounds in a quick contact of water and coffee. The coarser the grind the less accessible are the oils to the water, thus the inability to get out the strength from coffee not finely enough ground.

Too long contact of water and coffee causes twang and bitterness, and the finer the grind the less the contact should be. The infusion, when brewed, is injured by being boiled or overheated. It is also damaged by being chilled, which breaks the fusion of oils and water. It should be served immediately, or kept hot, as in a double boiler.

Tests show that water under the boiling point, 212°, is inefficient for coffee brewing, and does not extract the aromatic oils[378]. Used under this temperature, it is a sure cause of weak and insipid flavor. The effort to make up this deficiency by longer contact of coffee and water,

Comments (0)