All About Coffee, William H. Ukers [short story to read .txt] 📗

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Book online «All About Coffee, William H. Ukers [short story to read .txt] 📗». Author William H. Ukers

The first London coffee house resembled a fashionable club house in its later years, suitable for the "genteel" entertainments of the well-to-do Philadelphians. Ye coffee house was more of a commercial or public exchange. Evidence of the gentility of the London is given by John William Wallace:

The appointments of the London Coffee House, if we may infer what they were from the will of Mrs. Shubert [Shewbert] dated November 27, 1751, were genteel. By that instrument she makes bequest of two silver quart tankards; a silver cup; a silver porringer; a silver pepper pot; two sets of silver castors; a silver soup spoon; a silver sauce spoon, and numerous silver tablespoons and tea spoons, with a silver tea-pot.

Up to the outbreak of the American Revolution, it was more frequented than any other tavern in the Quaker city as a place of resort and entertainment, and was famous throughout the colonies

One of the many historic incidents connected with this old house was the visit there by William Penn's eldest son, John, in 1733, when he entertained the General Assembly of the province on one day and on the next feasted the City Corporation.

Roberts' Coffee House

Another house with some fame in the middle of the eighteenth century was Roberts' coffee house, which stood in Front Street near the first London house. Though its opening date is unknown, it is believed to have come into existence about 1740. In 1744 a British army officer recruiting troops for service in Jamaica advertised in the newspaper of the day that he could be seen at the Widow Roberts' coffee house. During the French and Indian War, when Philadelphia was in grave danger of attack by French and Spanish privateers, the citizens felt so great relief when the British ship Otter came to the rescue, that they proposed a public banquet in honor of the Otter's captain to be held at Roberts' coffee house. For some unrecorded reason the entertainment was not given; probably because the house was too small to accommodate all the citizens desiring to attend. Widow Roberts retired in 1754.

The James Coffee House

Contemporary with Roberts' coffee house was the resort run first by Widow James, and later by her son, James James. It was established in 1744, and occupied a large wooden building on the northwest corner of Front and Walnut Streets. It was patronized by Governor Thomas and many of his political followers, and its name frequently appeared in the news and advertising columns of the Pennsylvania Gazette.

The Second London Coffee House

Probably the most celebrated coffee house in Penn's city was the one established by William Bradford, printer of the Pennsylvania Journal. It was on the southwest corner of Second and Market Streets, and was named the London coffee house, the second house in Philadelphia to bear that title. The building had stood since 1702, when Charles Reed, later mayor of the city, put it up on land which he bought from Letitia Penn, daughter of William Penn, the founder. Bradford was the first to use the structure for coffee-house purposes, and he tells his reason for entering upon the business in his petition to the governor for a license: "Having been advised to keep a Coffee House for the benefit of merchants and traders, and as some people may at times be desirous to be furnished with other liquors besides coffee, your petitioner apprehends it is necessary to have the Governor's license." This would indicate that in that day coffee was drunk as a refreshment between meals, as were spirituous liquors for so many years before, and thereafter up to 1920.

Bradford's London coffee house seems to have been a joint-stock enterprise, for in his Journal of April 11, 1754, appeared this notice: "Subscribers to a public coffee house are invited to meet at the Courthouse on Friday, the 19th instant, at 3 o'clock, to choose trustees agreeably to the plan of subscription."

The building was a three-story wooden structure, with an attic that some historians count as the fourth story. There was a wooden awning one-story high extending out to cover the sidewalk before the coffee house. The entrance was on Market (then known as High) Street.

The London coffee house was "the pulsating heart of excitement, enterprise, and patriotism" of the early city. The most active citizens congregated there—merchants, shipmasters, travelers from other colonies and countries, crown and provincial officers. The governor and persons of equal note went there at certain hours "to sip their coffee from the hissing urn, and some of those stately visitors had their own stalls." It had also the character of a mercantile exchange—carriages, horses, foodstuffs, and the like being sold there at auction. It is further related that the early slave-holding Philadelphians sold negro men, women, and children at vendue, exhibiting the slaves on a platform set up in the street before the coffee house.

The resort was the barometer of public sentiment. It was in the street before this house that a newspaper published in Barbados, bearing a stamp in accordance with the provisions of the stamp act, was publicly burned in 1765, amid the cheers of bystanders. It was here that Captain Wise of the brig Minerva, from Pool, England, who brought news of the repeal of the act, was enthusiastically greeted by the crowd in May, 1766. Here, too, for several years the fishermen set up May poles.

Bradford gave up the coffee house when he joined the newly formed Revolutionary army as major, later becoming a colonel. When the British entered the city in September, 1777, the officers resorted to the London coffee house, which was much frequented by Tory sympathizers. After the British had evacuated the city, Colonel Bradford resumed proprietorship; but he found a change in the public's attitude toward the old resort, and thereafter its fortunes began to decline, probably hastened by the keen competition offered by the City tavern, which had been opened a few years before.

Bradford gave up the lease in 1780, transferring the property to John Pemberton, who leased it to Gifford Dally. Pemberton was a Friend, and his scruples about gambling and other sins are well exhibited in the terms of the lease in which said Dally "covenants and agrees and promises that he will exert his endeavors as a Christian to preserve decency and order in said house, and to discourage the profanation of the sacred name of God Almighty by cursing, swearing, etc., and that the house on the first day of the week shall always be kept closed from public use." It is further covenanted that "under a penalty of £100 he will not allow or suffer any person to use, or play at, or divert themselves with cards, dice, backgammon, or any other unlawful game."

The tavern (at the left) was regarded as the largest inn of the colonies and stood next to the Bank of Pennsylvania (center). From a print made from a rare Birch engraving

It would seem from the terms of the lease that what Pemberton thought were ungodly things, were countenanced in other coffee houses of the day. Perhaps the regulations were too strict; for a few years later the house had passed into the hands of John Stokes, who used it as dwelling and a store.

City Tavern or Merchants Coffee House

The last of the celebrated coffee houses in Philadelphia was built in 1773 under the name of the City tavern, which later became known as the Merchants coffee house, possibly after the house of the same name that was then famous in New York. It stood in Second Street near Walnut Street, and in some respects was even more noted than Bradford's London coffee house, with which it had to compete in its early days.

The City tavern was patterned after the best London coffee houses; and when opened, it was looked upon as the finest and largest of its kind in America. It was three stories high, built of brick, and had several large club rooms, two of which were connected by a wide doorway that, when open, made a large dining room fifty feet long.

Daniel Smith was the first proprietor, and he opened it to the public early in 1774. Before the Revolution, Smith had a hard struggle trying to win patronage from Bradford's London coffee house, standing only a few blocks away. But during and after the war, the City tavern gradually took the lead, and for more than a quarter of a century was the principal gathering place of the city. At first, the house had various names in the public mind, some calling it by its proper title, the City tavern, others attaching the name of the proprietor and designating it as Smith's tavern, while still others used the title, the New tavern.

The gentlefolk of the city resorted to the City tavern after the Revolution as they had to Bradford's coffee house before. However, before reaching this high estate, it once was near destruction at the hands of the Tories, who threatened to tear it down. That was when it was proposed to hold a banquet there in honor of Mrs. George Washington, who had stopped in the city in 1776 while on the way to meet her distinguished husband, then at Cambridge in Massachusetts, taking over command of the American army. Trouble was averted by Mrs. Washington tactfully declining to appear at the tavern.

After peace came, the house was the scene of many of the fashionable entertainments of the period. Here met the City Dancing Assembly, and here was held the brilliant fête given by M. Gerard, first accredited representative from France to the United States, in honor of Louis XVI's birthday. Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton, and other leaders of public thought were more or less frequent visitors when in Philadelphia.

The exact date when the City tavern became the Merchants coffee house is unknown. When James Kitchen became proprietor, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was so called. In 1806 Kitchen turned the house into a bourse, or mercantile exchange. By that time clubs and hotels had come into fashion, and the coffee-house idea was losing caste with the élite of the city.

In the year 1806 William Renshaw planned to open the Exchange coffee house in the Bingham mansion on Third Street. He even solicited subscriptions to the enterprise, saying that he proposed to keep a marine diary and a registry of vessels for sale, to receive and to forward ships' letter bags, and to have accommodations for holding auctions. But he was persuaded from the idea, partly by the fact that the Merchants coffee house seemed to be satisfactorily filling that particular niche in the city life, and partly because the hotel business offered better inducements. He abandoned the plan, and opened the Mansion House hotel in the Bingham residence in 1807.

In this setting for the first act of the play by Mary P. Hamlin and George Arliss, produced in 1918, the scenic artist aimed to give a true historical background, and combined the features of several inns and coffee houses in Philadelphia, Virginia, and New England as they existed in Washington's first administration

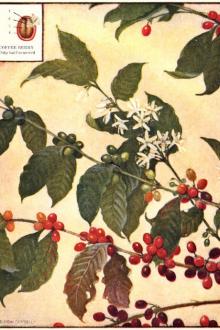

Chapter XV THE BOTANY OF THE COFFEE PLANTIts complete classification by class, sub-class, order, family,

Comments (0)