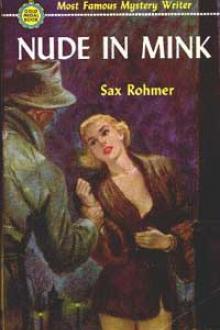

Nude in Mink, Sax Rohmer [free children's ebooks pdf TXT] 📗

- Author: Sax Rohmer

- Performer: -

Book online «Nude in Mink, Sax Rohmer [free children's ebooks pdf TXT] 📗». Author Sax Rohmer

Donovan considered the name for a moment, and then, “Yes,” he replied. “Used to be in your Indian Civil Service, and afterwards for a while was an Assistant Commissioner at Scotland Yard.”

“That’s my man. His unsavoury private life led to his retirement, although he was, professionally, a brilliant success. Well, he lives in Charles Street. I had hoped to save him. But the fact that all approaches to his house are efficiently patrolled leads me to fear the worst—”

“The police—”

“Police my grandmother! He has been marked down by one of the few first class brains in the world. The entire Force couldn’t save him! There’s just one chance, and its success depends upon my getting at Tristram personally.”

“This thing sounds—”

“Like lunacy? It does. But it’s real,” Maitland picked up his waterproof. ‘They don’t know where I have gone. So, with fair luck we may get across Berkeley Square, now the railings are down, without being spotted. Once in Charles Street the fun begins!—What’s that?”

He paused abruptly, the blue coat over his arm. He listened, and Donovan, stricken motionless in turn listened also.

Footsteps in the otherwise silent street, of which vaguely both had been aware, had stopped immediately below the windows. Donovan stood there, questioning Maitland with his eyes.

The footsteps passed on.

“Only someone pausing to strike a light.”

Maitland nodded. “Maybe. Mustn’t get jumpy. Listen, Donovan. Tristram’s one resident servant—a man called Harper—is standing by to open the door the moment I get there. (Same arrangement that I made with you.) Jump into this waterproof.”

“What! Why?”

“I am prepared to learn from the enemy. Those cunning devils tried to get me arrested by a passing policeman! You might be mistaken for a plain clothes man anywhere. Haven’t got a bowler hat, I suppose?”

“I have not,” Donovan replied, as Maitland forcibly helped him into the coat.

“Soft brim one, then. If anyone tries to stop us, just say ‘Police force. Stand aside’—they won’t spot your American accent—and hang on to my arm as if you had me in custody. They will think their trick has worked after all and that you are taking me to the lock-up. If they don’t”—he thrust an automatic into Donovan’s hand—“show ‘em that! Come on. Where’s your hat?”

4

Of that nightmare scurry along Bruton Street and across Berkeley Square, Donovan’s impressions were hazy, except that, aided by the now friendly fog which hemmed them in like a prison wall, it represented, later, a crossing of the borderline; it had swept him from a rather weary world he knew into a world whose existence he had never even suspected, a world of horrors unimagined.

At the corner of Charles Street: “Here they are!” breathed Maitland. “Grab my arm. Play up.” Then, raising his voice, “I tell you, my man,” he shouted, “that you are making a damn fool of yourself. I am a British officer. My business here is urgent “

“You can either come quietly or have the bracelets on,” Donovan replied in a loud gruff voice.

Two short, stocky figures had manifested from somewhere, and loomed threateningly just ahead. Donovan pushed Maitland forward.

“I warn you, constable,” Maitland exclaimed. “I am known to your superiors. This will mean back to the beat for you.”

“Move on there!” Donovan ordered the skulking pair, who seemed to be closing in. “I am a police officer.”

Both fell back as they passed, and Donovan had never a glimpse of their faces,

“I demand to be taken to …”

“You’ll be taken where I take you!”

“Next door but one,” murmured Maitland. “Pray heaven Harper is standing by!”

A moment later he plunged suddenly to the left and Donovan heard a muffled bell ringing behind same invisible door. It rang three times quickly and then twice slowly. A narrow oblong, dimly luminous in the darkness, became visible.

“All lights out, Harper! In you come, Donovan.”

Donovan hurled himself at the vague doorway, fell over an unseen obstacle, and sprawled on the carpet. He heard the door bang. It silenced racing footsteps which swept up behind. Then came a crashing blow on the door. Someone shot a bolt into place, and as Donovan stood up, a voice right beside him said, nervously:

“Dr. Steel Maitland, sir?”

“Here,” came Maitland’s voice. “You all right, Donovan?”

“I think so!”

“Is there any other way in, Harper?”

“No, sir. May I turn on the light?”

“Yes.”

A switch clicked and they found themselves in a miniature panelled entrance hall, doors right and left, and a stairway ahead. Harper, the manservant, proved to be a flabby type, pallid (but this was no cause for wonder) and having the heavy sensual jowl of a tired Silenus. He stood staring at them, his lips twitching.

“Sir Miles?” Maitland asked sharply.

“Is in his study, sir. He requested that I should not disturb him.”

“I imagine the clatter of our arrival will have done so, however. He is well?”—“He was his usual self when I was last in the study, sir.”

Maitland’s teeth glittered through his black beard as he turned to Donovan. “Second try to our side: Lead the way, Harper.”

“Certainly, sir.”

Harper, quite obviously, had been reduced to a state of utter bewilderment: his expression was pathetic. Ascending to the first floor of this cramped little house, he rapped on a door, opened it, and announced:

“Dr. Steel Maitland, sir, and another gentleman.”

Harper stood aside as Maitland and Donovan entered—and never, to the end of their days, did Donovan or Maitland forget the study of Sir Miles Tristram.

It was a small oblong room with a low ceiling, and its atmosphere struck one as unpleasantly stuffy. This was due in part to the presence of heavy window curtains, in part to that indefinable smell which belongs to ancient volumes, old furniture, to certain kinds of relics—and in part to something else.

Several shelves bulged with books, almost exclusively of an erotic Character. There were some reproductions of Pompeian frescoes, and the available wall space was otherwise filled with figure studies of a more than startling character.

There were a number of statuettes which would have shocked the most liberal-minded observer and some framed photographs of an artistic depravity which certainly shocked Donovan.

Indian antiques, chiefly sadistic in design, crowded a glazed cabinet: and the room was strangely still.

At its further end, an old carved walnut desk was placed in a book-lined recess. Immediately above the chair behind it hung a square oil painting which the American journalist decided he could not attempt to describe in print otherwise than to say that it represented a grotesque god seated cross-legged on a golden dais, obese and leering, laved in the smoke of incense, to whom votaries male and female made obscene offerings.

Upon the desk, in addition to an untidy mass of papers, they saw an open jewel-case as large as a painter’s portfolio, containing the most wonderfully graded collection of Oriental sapphires which either had ever set eyes upon. The range of colour was amazing, the manner of their disposition worthy of a great artist. Under the light of a reading lamp which burned on the desk they glowed with the magic of Arabian fable.

And in the chair, hunched forward, one podgy hand clenched on the desk, and the other resting on a Chinese snuffbox, was Sir Miles Tristram, a vast carnal figure, his face that of an aged satyr, his several chins bulging over the collar of his dinner jacket; lascivious god of the picture incarnated in gross flesh.

Something peculiar in his appearance brought Donovan up with a start as he crossed the threshold. Staring hard, he saw what it was. Tristram had a watchmaker’s glass screwed into his right eye. He was uncannily still.

“Good evening, Tristram.”

Steel Maitland spoke clearly, indeed loudly. But Sir Miles Tristram did not move. Maitland stepped forward.

“You were expecting me, I believe?”

But the man hunched over the desk never stirred. Some slight draught set up in that stagnant air by their entrance crept around the recess; it fluttered a few straggling hairs upon the nearly bald massive bowed head.

“Maitland!” Donovan whispered, “he is unnaturally still. See! He never moves… and he is clutching something in his hand!”

“Stand back, Donovan! Don’t touch him. Stand back. Leave it to me.”

In two long strides Maitland was behind the desk, bending over the seated man. He grasped those heavy, slumped shoulders and pulled. The figure remained immovable. Donovan heard Maitland’s teeth snap together as he clenched his jaws.

He pulled again, then desisted—and slowly straightened himself. His eyes, when he stared across at Donovan, shone brightly as two of Sir Miles’s gems.

“I was wrong, Donovan,” he said quietly. “The second try was not to us.”

“ENDEAVOUR to be quite exact, Harper. Omit no detail.”

In a constricted but perfectly formal dining-room, Harper faced Maitland and Donovan. Here, were no traces of that pathological eroticism which fouled Sir Miles’s sanctum. The manservant looked more flabby and fishlike than ever. He knew that his master was dead, but Maitland had not permitted him to enter the study. That ghastly spectacle, and recognition of the astounding rigidity of Tristram’s body, had induced a sudden nausea in Donovan’s case, from which he was by no means fully recovered.

Harper moistened twitching lips.

“At the time that you phoned, sir, and I answered your call, the lady I have mentioned was with Sir Miles.”

“How long had she been there?”

“Not more than five minutes.”

“Was she present when you delivered my message?”

“She was, sir.”

“What was she doing?”

“She was sitting facing Sir Miles across the desk, and a green sapphire lay between them. Her finger was touching it as I came in.”

“What exactly, did you say?”

“I said—” Harper closed his eyes in an effort of concentration—“Dr. Steel Maitland has just phoned, sir, and requests that you will remain at home until he arrives. Just what you told me—ahem—to say.”

“Exactly. What did he reply?”

“Nothing, sir. He simply nodded and handed me his snuffbox—which I took away and refilled.”

Steel Maitland, who had been swaying from foot to foot as though the floor were a moving deck, stood stock still.

“You did what?”

“Refilled Sir Miles’s snuffbox, sir. It was one of my duties.”

Maitland stared so hard that Harper ceased speaking as he watched him. “Had you forgotten to fill it, then?”

“Not at all, sir—at least—not to the best of my recollection. But Sir Miles used a large quantity of snuff, and when I went to give him your message, he held out his snuffbox and said (I report—ahem—his exact words): ‘Why the hell haven’t you filled my snuffbox?’ I therefore carried it down, cleaned it, as is my custom, refilled it and took it back. That was the last time—I saw him, sir.”

Something oddly like emotion moved Harper, and Steel Mainland’s manner underwent a subtle change.

“I am obliged to you, Harper. I am to understand, then, that to the best of your knowledge Sir Miles’s snuffbox had been filled as usual, but that when he handed it to you it was empty?”

“I couldn’t say exactly empty, sir. There was just a little dust at the bottom, but not sufficient for—ahem—a pinch.”

“You say you cleaned the box. In what way?”

“I washed it out thoroughly, and dried it with a clean leather before refilling it.”

Steel Maitland nodded. “Bad luck. Had you ever seen this woman before?”

“No, sir. But I believe she had phoned. I

Comments (0)