The Lust of Hate, Guy Newell Boothby [essential books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Guy Newell Boothby

- Performer: -

Book online «The Lust of Hate, Guy Newell Boothby [essential books to read .txt] 📗». Author Guy Newell Boothby

on the ground, could scarcely be imagined. I watched until the man I

had followed returned with an ambulance stretcher, and then

accompanied the mournful cortege a hundred yards or so on its

way to the hospital. Then, being tired of the matter, I branched off

the track, and prepared to make my way back to my hotel as fast as my

legs would take me.

My thoughts were oppressed with what I had seen. There was a grim

fascination about the recollection of the incident that haunted me

continually, and which I could not dispel, try how I would. I

pictured Bartrand lying in the snow exactly as I had seen the other,

and fancied myself coming up and finding him. At that moment I was

passing Charing Cross Railway Station. With the exception of a

policeman sauntering slowly along on the other side of the street, a

drunken man staggering in the road, and a hansom cab approaching us

from Trafalgar Square, I had the street to myself. London slept while

the snow fell, and murder was being done in her public thoroughfares.

The hansom came closer, and for some inscrutable reason I found

myself beginning to take a personal interest in it. This interest

became even greater when, with a spluttering and sliding of feet, the

horse came to a sudden standstill alongside the footpath where I

stood. Next moment a man attired in a thick cloak threw open the

apron and sprang out.

“Mr. Pennethorne, I believe?” he said, stopping me, and at the

same time raising his hat.

“That is my name,” I answered shortly, wondering how he knew me

and what on earth he wanted. “What can I do for you?”

He signed to his driver to go, and then, turning to me, said, at

the same time placing his gloved hand upon my arm in a confidential

way:

“I am charmed to make your acquaintance. May I have the pleasure

of walking a little way with you? I should be glad of your society,

and I can then tell you my business.”

His voice was soft and musical, and he spoke with a peculiar

languor that was not without its charm. But as I could not understand

what he wanted with me, I put the question to him as plainly as I

could without being absolutely rude, and awaited his answer. He gave

utterance to a queer little laugh before he replied:

“I want the pleasure of your company at supper for one thing,” he

said. “And I want to be allowed to help you in a certain matter in

which you are vitally interested, for another. The two taken together

should, I think, induce you to give me your attention.”

“But I don’t know you,” I blurted out. “To the best of my belief I

have never set eyes on you before. What business, therefore, can you

have with me?”

“You shall know all in good time,” he answered. “In the meantime

let me introduce myself. My name is Nikola. I am a doctor by

profession, a scientist by choice. I have few friends in London, but

those I have are the best that a man could desire. I spend my life in

the way that pleases me most; that is to say, in the study of human

nature. I have been watching you since you arrived in England, and

have come to the conclusion that you are a man after my own heart. If

you will sup with me as I propose, I don’t doubt but that we shall

agree admirably, and what is more to the point, perhaps, we shall be

able to do each other services of inestimable value. I may say

candidly that it lies in your power to furnish me with something I am

in search of. I, on my part, will, in all probability, be able to put

in your way what you most desire in the world.”

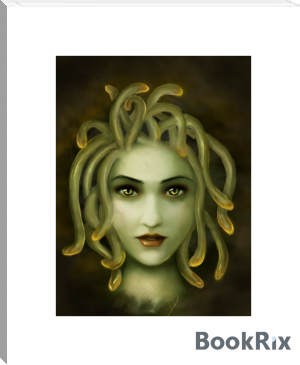

I stopped in my walk and faced him. Owing to the broad brim of his

hat, and the high collar of his cape, I could scarcely see his face.

But his eyes rivetted my attention at once.

“And that is?” I said.

“Revenge,” he answered, simply. “Believe me, my dear Mr.

Pennethorne, I am perfectly acquainted with your story. You have been

wronged; you desire to avenge yourself upon your enemy. It is a very

natural wish, and if you will sup with me as I propose, I don’t doubt

but that I can put the power you seek into your hands. Do you

agree?”

All my scruples vanished before that magic word revenge,

and, strange as it my seem, without more ado I consented to his

proposal. He walked into the road and, taking a whistle from his

pocket, blew three staccato notes upon it. A moment later the

hansom from which he had jumped to accost me appeared round a corner

and came rapidly towards us. When it pulled up at the kerb, and the

apron had been opened, this peculiar individual invited me to take my

place in it, which I immediately did. He followed my example, and sat

down beside me, and then, without any direction to the driver, we set

off up the street.

For upwards of half-an-hour we drove on without stopping, but in

which direction we were proceeding I could not for the life of me

discover. The wheels were rubber-tyred and made no noise upon the

snow-strewn road; my companion scarcely spoke, and the only sound to

be heard was the peculiar bumping noise made by the springs, the soft

pad-pad of the horse’s hoofs, and an occasional grunt of

encouragement from the driver. At last it became evident that we were

approaching our destination. The horse’s pace slackened; I detected

the sharp ring of his shoes on a paved crossing, and presently we

passed under an archway and came to a standstill.

“Here we are at last, Mr. Pennethorne,” said my mysterious

conductor. “Allow me to lift the glass and open the apron.”

He did so, and then we alighted. To my surprise we stood in a

square courtyard, surrounded on all sides by lofty buildings. Behind

the cab was a large archway, and at the further end of it the gate

through which we had evidently entered. The houses were in total

darkness, but the light of the cab lamps was sufficient to show me a

door standing open on my left hand.

“I’m afraid you must be very cold, Mr. Pennethorne,” said Nikola,

for by that name I shall henceforth call him, as he alighted, “but if

you will follow me I think I can promise that you shall soon be as

warm as toast.”

As he spoke he led the way across the courtyard towards the door I

have just mentioned. When he reached it he struck a match and

advanced into the building. The passage was a narrow one, and from

its appearance, and that of the place generally, I surmised that the

building had once been used as a factory of some kind. Half-way down

the passage a narrow wooden staircase led up to the second floor, and

in Indian file we ascended it. On reaching the first landing my guide

opened a door which stood opposite him, and immediately a bright

light illumined the passage.

“Enter, Mr. Pennethorne, and let me make you welcome to my poor

abode,” said Nikola, placing his hand upon my shoulder and gently

pushing me before him.

I complied with his request, half expecting to find the room

poorly furnished. To my surprise, however, it was as luxuriously

appointed as any I had ever seen. At least a dozen valuable

pictures—I presume they must have been valuable, though personally I

know but little about such things—decorated the walls; a large and

quaintly-carved cabinet stood in one corner and held a multitude of

china vases, bowls, plates, and other knick-knacks; a massive oak

sideboard occupied a space along one wall and supported a quantity of

silver plate; while the corresponding space upon the opposite wall

was filled by a bookcase reaching to within a few inches of the

ceiling, and crammed with works of every sort and description. A

heavy pile carpet, so soft that our movements made no sound upon it,

covered the floor; luxurious chairs and couches were scattered about

here and there, while in an alcove at the farther end was an

ingenious apparatus for conducting chemical researches. Supper was

laid on the table in the centre, and when we had warmed ourselves at

the fire that glowed in the grate, we sat down to it. As if to add

still further to my surprise, when the silver covers of the dishes

were lifted, everything was found to be smoking hot. How this had

been managed I could not tell, for our arrival at that particular

moment could not have been foretold with any chance of certainty, and

I had seen no servant enter the room. But I was very hungry,

and as the supper before me was the best I had sat down to for

years, you may suppose I was but little inclined to waste time on a

matter of such trivial importance.

When we had finished and I had imbibed the better part of two

bottles of Heidseck, which my host had assiduously pressed upon me,

we left the table and ensconced ourselves in chairs on either side of

the hearth. Then, for the first time, I was able to take thorough

stock of my companion. He was a man of perhaps a little above middle

height, broad shouldered, but slimly built. His elegant proportions,

however, gave but a small idea of the enormous strength I afterwards

discovered him to possess. His hair and eyes were black as night, his

complexion was a dark olive hue, confirming that suspicion of foreign

extraction which his name suggested, but of which his speech afforded

no trace. He was attired in faultless evening dress, the dark colour

of which heightened the extraordinary pallor of his complexion.

“You have a queer home here, Dr. Nikola!” I said, as I accepted

the cheroot he offered me.

“Perhaps it is a little out of the common,” he answered, with one

of his queer smiles; “but then that is easily accounted for. Unlike

the general run of human beings, I am not gregarious. In other words,

I am very much averse to what is called the society of my fellow man;

I prefer, under most circumstances, to live alone. At times, of

course, that is not possible. But the idea of living in a flat, shall

we say, with perhaps a couple of families above me, as many on either

side, and the same number below; or in an hotel or a boarding-house,

in which I am compelled to eat my meals in company with

half-a-hundred total strangers, is absolutely repulsive to me. I

cannot bear it, and therefore I choose my abode elsewhere. A private

dwelling-house I might, of course, take, but that would necessitate

servants and other incumbrances; this building suits my purposes

admirably. As you may have noticed, it was once a boot and shoe

factory; but after the proprietor committed suicide by cutting his

throat—which, by the way, he did in this very room—the business

failed; and until I fell across it, it was supposed to be haunted,

and, in consequence, has remained untenanted.”

“But do you mean to say you live here alone?” I enquired,

surprised at the queerness of the idea.

“In a certain sense, yes—in another, no. That is, I have a deaf

and dumb Chinese servant who attends to my simple wants, and a cat

who for years has never left me.”

“You surprise me

Comments (0)