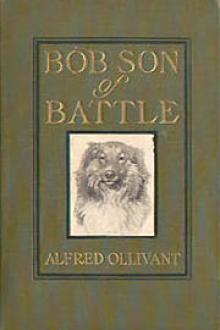

Bob, Son of Battle, Alfred Ollivant [graded readers txt] 📗

- Author: Alfred Ollivant

- Performer: -

Book online «Bob, Son of Battle, Alfred Ollivant [graded readers txt] 📗». Author Alfred Ollivant

“Thank ye, lad,” he said. “But I reck’n we can ‘fend for oorsel’s, Bob and I. Eh, Owd Un?”

Anxious as David might be, he was not so anxious as to be above taking a mean advantage of this state of strained apprehension to work on Maggie’s fears.

One evening he was escorting her home from church, when, just before they reached the larch copse: “Goo’ sakes! What’s that?” he ejaculated in horror-laden accents, starting back.

“What, Davie?” cried the girl, shrinking up to him all in a tremble.

“Couldna say for sure. It mought be owt, or agin it mought be nowt. But yo’ grip my arm, I’ll grip yo’ waist.”

Maggie demurred.

“Canst see onythin’?” she asked, still in a flutter.

“Be’ind the ‘edge.”

“Wheer?”

“Theer! “—pointing vaguely.

“I canna see nowt.”

“Why, theer, lass. Can yo’ not see? Then yo’ pit your head along o’ mine—so–closer–- closer.” Then, in aggrieved tones: “Whativer is the matter wi’ yo’, wench? I might be a leprosy.”

But the girl was walking away with her head high as the snow-capped Pike.

“So long as I live, David M’Adam,” she cried, “I’ll niver go to church wi’ you agin!”

“Iss, but you will though-.-onst,” he answered low.

Maggie whisked round in a flash, superbly indignant.

“What d’yo’ mean, sir-r-r?”

“Yo’ know what I mean, lass,” he replied sheepish and shuffling before her queenly anger.

She looked him up and down, and down and up again.

“I’ll niver speak to you agin, Mr. M’Adam, she cried; “not if it was ever so—Nay, I’ll walk home by myself, thank you. I’ll ha’ nowt to do wi’ you.”

So the two must return to Kenmuir, one behind the other, like a lady and her footman..

David’s audacity had more than once already all but caused a rupture between the pair. And the occurrence behind the hedge set the cap on his impertinences. That was past enduring and Maggie by her bearing let him know it.

David tolerated the girl’s new attitude for exactly twelve minutes by the kitchen clock. Then: “Sulk wi’ me, indeed! I’ll teach her!” and he marched out of the door, “Niver to cross it agin, ma word!”

Afterward, however, he relented so far as to continue his visits as before; but he made. it clear that he only came to see the Master and hear of Owd Bob’s doings. On these occasions he loved best to sit on the window-sill outside the kitchen, and talk and chaff with Tammas and the men in the yard, feigning an uneasy bashfulness was reference made to Bessie Boistock. And after sitting thus for some time, he would half turn, look over his.

the girl within: “Oh, good-evenin’! I forgot yo’, “—and then resume his conversation. While the girl within, her face a little pinker, her lips a little tighter, and her chin a little higher, would go about her business, pretending neither to hear nor care.

The suspicions that M’Adam nourished dark designs against James Moore were somewhat confirmed in that, on several occasions in the bitter dusks of January afternoons, a little insidious figure was reported to have been seen lurking among the farm-buildings of Kenmuir.

Once Sam’l Todd caught the little man fairly, skulking away in the woodshed. Sam’l took him up bodily and carried him down the slope to the Wastrel, shaking him gently as he went.

Across the stream he put him on his feet.

“If I catches yo’ cadgerin’ aroun’ the farm agin, little mon,” he admonished, holding up a warning finger; “I’ll tak’ yo’ and drap yo’ in t’ Sheep-wash, I warn yo’ fair. I’d ha’ done it noo an’ yo’d bin a bigger and a younger mon. But theer! yo’m sic a scrappety bit. Noo, nfl whoam.” And the little man slunk silently away.

For a time he appeared there no more. Then, one evening when it was almost dark, James Moore, going the round of the outbuildings, felt Owd Bob stiffen against his side.

and, dropping his hand on the old dog’s neck felt a ruff of rising hair beneath it.

“Steady, lad, steady,” he whispered; “what is ‘t?” He peered forward into the gloom; and at length discerned a little familiar figure huddled away in the crevice between two stacks.

“It’s yo, is it, M’Adam?” he said, and, bending, seized a wisp of Owd Bob’s coat in a grip like a vice.

Then, in a great voice, moved to rare anger. “Oot o’ this afore I do ye a hurt, ye meeserable spyin’ creeturt” he roared. “Yo’ mun wait. till dark cooms to hide yo’, yo’ coward, afore yo daur coom crawlin’ aboot ma hoose, frightenin’ the women-folk and up to yer devilments. If yo’ve owt to say to me, coom like a mon in the open day. Noo git aff wi’ yo’, afore I lay hands to yo’!”

He stood there in the dusk, tall and mighty, a terrible figure, one hand pointing to the gate, the other still grasping the gray dog.

The little man scuttled away in the halflight, and out of the yard.

On the plank-bridge he turned and shook his fist at the darkening house.

“Curse ye, James Moore!” he sobbed, “I’ll be even wi’ ye yet.”

Chapter XV. DEATH ON THE MARCHES

ON the top of this there followed an attempt to poison Th’ Owd Un. At least there was no other accounting for the affair.

In the dead of a long-remembered night James Moore was waked by a low moaning beneath his room. He leapt out of bed and ran to the window to see his favorite dragging about the moonlit yard, the dark head down, the proud tail for once lowered, the lithe limbs wooden, heavy, unnatural—altogether pitiful.

In a moment he was downstairs and out to his friend’s assistance. “Whativer is’t, Owd Un?” he cried in anguish.

At the sound of that dear voice the old dog tried to struggle to him, could not, and fell, whimpering.

In a second the Master was with him, examining him tenderly, and crying for Sam’l, who slept above the stables.

There was every symptom of foul play: the tongue was swollen and almost black; the breathing labored; the body twiched horribly; and the soft gray eyes all bloodshot and straining in agony.

With the aid of Sam’l and Maggie, drenching first and stimulants after, the Master pulled him around for the moment. And soon Jim Mason and Parson Leggy, hurriedly summoned, came running hot-foot to the rescue.

Prompt and stringent measures saved the victim—but only just. For a time the best sheepdog in the North was pawing at the Gate of Death. In the end, as the gray dawn broke, the danger passed.

The attempt to get at him, if attempt it was, aroused passionate indignation in the countryside. It seemed the culminating-point of the excitement long bubbling.

There were no traces of the culprit; not a vestige to lead to incrimination, so cunningly had the criminal accomplished his foul task. But as to the perpetrator, if there where no proofs there were yet fewer doubts.

At the Sylvester Arms Long Kirby asked M’Adam point-blank for his explanation of the matter.

“Hoo do I ‘count for it?” the little man cried. “I dinna ‘count for it ava.”

“Then hoo did it happen?” asked Tammas with asperity.

“I dinna believe it did happen,” the little man replied. “It’s a lee o’ James Moore’s— a charactereestic lee.” Whereon they chucked him out incontinently; for the Terror for once was elsewhere.

Now that afternoon is to be remembered for threefold causes. Firstly, because, as has been said, M’Adam was alone. Secondly, because, a few minutes after his ejectment, the window of the tap-room was thrown open from without, and the little man looked in. He spoke no word, but those dim, smouldering eyes of his wandered from face to face, resting for a second on each, as if to burn them on his memory. “I’ll remember ye, gentlemen,” he said at length quietly, shut the window, and was gone.

Thirdly, for a reason now to be told.

Though ten days had elapsed since the attempt on him, the gray dog had never been his old self since. He had attacks of shivering; his vitality seemed sapped; he tired easily, and, great heart, would never own it. At length on this day, James Moore, leaving the old dog behind him, had gone over to Grammochtown to consult Dingley, the vet. On his way home he met Jim Mason with Gyp, the faithful Betsy’s unworthy successor, at the Dalesman’s Daughter. Together they started for the long tramp home over the Marches. And that journey is marked with a red stone in this story.

All day long the hills had been bathed in inpenetrable fog. Throughout there had been an accompanying drizzle; and in the distance the wind had moaned a storm-menace. To the darkness of the day was added the sombreness of falling night as the three began the ascent of the Murk Muir Pass. By the time they emerged into the Devil’s Bowl it was altogether black and blind. But the threat of wind had passed, leaving utter stillness; and they could hear the splash of an otter on the far side of the Lone Tarn as they skirted that gloomy water’s edge. When at length the last steep rise on to the Marches had been topped, a breath of soft air smote them lightly, and the curtain of fog began drifting away.

The two men swung steadily through the heather with that reaching stride the birthright of moor-men and highianders. They talked but little, for such was their nature: a word or two on sheep and the approaching lambingtime; thence on to the coming Trials; the Shepherds’ Trophy; Owd Bob and the attempt on him; and from that to M’Adam and the Tailless Tyke,

“D’yo’ reck’n M’Adam had a hand in’t?” the postman was asking.

“Nay; there’s no proof.”

“Ceptin’ he’s mad to get shut o’ Th’ Owd Un afore Cup Day.”

or me—it mak’s no differ.” For a dog is disqualified from competing for the Trophy who has changed hands during the six months prior to the meeting. And this holds good though the change be only from father to son on the decease of the former.

Jim looked up inquiringly at his companion.

“D’yo’ think it’ll coorn to that?” he asked.

“What?”

“Why—murder

“Not if I can help it,” the other answered grimly.

The fog had cleared away by now, and the moon was up. To their right, on the crest of a rise some two hundred yards away, a low wood stood out black against the sky. As they passed it, a blackbird rose up screaming, and a brace of wood-pigeons winged noisily away.

“Hullo! hark to the yammerin’!” muttered Jim, stopping; “and at this time o’ night too!”

Some rabbits, playing in the moonlight on the outskirts of the wood, sat up, listened, and hopped back into security. At the same moment a big hill-fox slunk out of the covert. He stole a pace forward and halted, listening with one ear back and one pad raised; then cantered silently away in the gloom, passing close to the two men and yet not observing them.

“What’s up, I wonder?” mused the postman.

“The fox set ‘em clackerin’, I reck’n,” said the Master.

“Not he; he was scared ‘maist oot o’ his skin,” the other answered. Then in tones of suppressed excitement, with his hands on James Moore’s arm: “And, look’ee, theer’s ma Gyp a-beckonin’ on us!”

There, indeed, on the crest of the rise beside the wood, was the little lurcher, now looking back at his master, now creeping stealthily forward.

“Ma word! theer’s summat wrong yonder!” cried Jim, and jerked the post-bags off his shoulder. “Coom on, Master! “—and he set off running toward the dog; while James Moore, himself excited now, followed with an agility that

Comments (0)