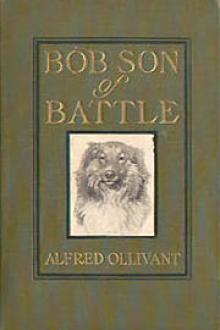

Bob, Son of Battle, Alfred Ollivant [graded readers txt] 📗

- Author: Alfred Ollivant

- Performer: -

Book online «Bob, Son of Battle, Alfred Ollivant [graded readers txt] 📗». Author Alfred Ollivant

The gentle, implacable voice ceased. The girl turned and slipped softly out of the room; and M’Adam was left alone to his thoughts and his dead wife’s memory.

“Mither and father, baith! Mither and father, baith!” rang remorselessly in his ears.

THE Black Killer still cursed the land. Sometimes there would be a cessation in the crimes; then a shepherd, going his rounds, would notice his sheep herding together, packing in unaccustomed squares; a raven, gorged to the crop, would rise before him and flap wearily away, and he would come upon the murderer’s latest victim.

The Dalesmen were in despair, so utterly futile had their efforts been. There was no proof; no hope, no apparent probability that the end was near. As for the Tailless Tyke, the only piece of evidence against him had flown with David, who, as it chanced, had divulged what he had seen to no man.

The 100 pound reward offered had brought no issue. The police had done nothing. The Special Commissioner had been equally successful. After the affair in the Scoop the Killer never ran a risk, yet never missed a chance.

Then, as a last resource, Jim Mason made his attempt. He took a holiday from his duties and disappeared into the wilderness. Three days and three nights no man saw him.

On the morning of the fourth he reappeared, haggard, unkempt, a furtive look haunting his eyes, sullen for once, irritable, who had never been irritable before—to confess his failure. Cross-examined further, he answered with unaccustomed fierceness: “I seed nowt, I tell ye. Who’s the liar as said I did?”

But that night his missus heard him in his sleep conning over something to himself in slow, fearful whisper, “Two on ‘em; one ahint t’other. The first big—bull-like; t’ither—” At which point Mrs. Mason smote him a smashing blow in the ribs, and he woke in a sweat, crying terribly, “Who said I seed—”

The days were slipping away; the summer was hot upon the land, and with it the Black Killer was forgotten; David was forgotten; everything sank into oblivion before the all-absorbing interest of the coming Dale trials.

The long-anticipated battle for the Shepherds’ Trophy was looming close; soon everything that hung upon the issue of that struggle would be decided finally. For ever the jus-. tice of Th’ Owd Un’ claim to his proud title would be settled. If he won, he won outright —a thing unprecedented in the annals of the Cup; if he won, the place of Owd Bob o’ Kenmuir as first in his profession was assured for all time. Above all, it was the last event in the six years’ struggle ‘twixt Red and Gray It wa the last time those two great rivals would meet in battle. The supremacy of one would be decided once and for all. For win or lose, it was the last public appearance of the Gray Dog of Kenmuir.

And as every hour brought the great day nearer, nothing else was talked of in the countryside. The heat of the Dalesmen’s enthusiasm was only intensified by the fever of their apprehension. Many a man would lose more than he cared to contemplate were ‘Th’ Owd Un beat. But he’d not be! Nay; owd, indeed, he was—two years older than his great rival; there were a hundred risks, a hundred chances; still: “What’s the odds agin Owd Bob o’ Kenmuir? I’m takin’ ‘em. Who’ll lay agin Th’ Owd Un?”

And with the air saturated with this perpetual talk of the old dog, these everlasting references to his certain victory; his ears drumming with the often boast that the gray dog was the best in the North, M’Adam became the silent, ill-designing man of six months since—morose, brooding, suspicious, muttering of conspiracy, plotting revenge.

The scenes at the Sylvester Arms were replicas of those of previous years. Usually the little man sat isolated in a far corner, silent and glowering, with Red Wull at his feet. Now and then he burst into a paroxysm of insane giggling, slapping his thigh, and muttering, “Ay, it’s likely they’ll beat us, Wuflie. Yet aiblins there’s a wee somethin’—a somethin’ we ken and they dinna, Wullie,—eh! Wullie, he! he!” And sometimes he would leap to his feet and address his pot-house audience, appealing to them passionately, satirically, tearfully, as the mood might be on him; and his theme was always the same: James Moore, Owd Bob, the Cup, and the plots agin him and his Wullie; and always he concluded with that hint of the surprise to come.

Meantime, there was no news of David; he had gone as utterly as a ship foundered in mid-Atlantic. Some said he’d ‘listed; some, that he’d gone to sea. And “So he ‘as,” corroborated Sam’l, “floatin’, ‘eels uppards.”

With no gleam of consolation, Maggie’s misery was such as to rouse compassion in all hearts. She went no longer blithely singing about her work; and all the springiness had fled from her gait. The people of Kenmuir vied with one another in their attempts to console their young mistress.

Maggie was not the only one in whose life David’s absence had created a void. Last as he would have been to own it, M’ Adam felt acutely the boy’s loss. It may have been he missed the ever-present butt; it may have been a nobler feeling. Alone with Red Wull, too late he felt his loneliness. Sometimes, sitting in the kitchen by himself, thinking of the past, he experienced sharp pangs of remorse; and this was all the more the case after Maggie’s visit. Subsequent to that day the little man, to do him justice, was never known to hint by word or look an ill thing of his enemy’s daughter. Once, indeed, when Melia Ross was drawing on a dirty imagination with Maggie for subject, M’Adam shut her up with:

“Ye’re a maist amazin’ big liar, Melia Ross.” Yet, though for the daughter he had now no evil thought, his hatred for the father had never been so uncompromising.

He grew reckless in his assertions. His life was one long threat against James Moore’s. Now he openly stated his conviction that, on the evenful night of the fight, James Moore, with object easily discernible, had egged David on to murder him.

“Then why don’t yo’ go and tell him so, yo’ muckle liar?” roared Tammas at last, enraged to madness.

“I will!” said M’Adam. And he did.

It was on the day preceding the great summer sheep fair at Grammochtown that he ful-. filled his vow.

That is always a big field-day at Kenmuir; and on this occasion James Moore and Owd Bob had been up and working on the Pike from the rising of the sun. Throughout the straggling lands of Kenmuir the Master went with his untiring adjutant, rounding up, cutting out, drafting. It was already noon when the flock started from the yard.

On the gate by the stile, as the party came up, sat M’Adam.

“I’ve a word to say to you, James Moore,” he announced, as the Master approached.

“Say it then, and quick. I’ve no time to stand gossipin’ here, if yo’ have,” said the Master.

M’Adam strained forward till he nearly toppled off the gate.

Queer thing, James Moore, you should be the only one to escape this Killer.”

“Yo’ forget yoursel’, M’Adam.”

“Ay, there’s me,” acquiesced the little man. “But you—hoo d’yo’ ‘count for your luck?”

James Moore swung round and pointed proudly at the gray dog, now patrolling round the flock.

“There’s my luck!” he said.

M’Adam laughed unpleasantly.

“So I thought,” he said, “so I thought! And I s’pose ye’re thinkin’ that yer luck,” nodding at the gray dog, “will win you the Cup for certain a month hence,”

“I hope so!” said the Master.

“Strange if he should not after all,” mused the little man.

James Moore eyed him suspiciously. “What d’yo’ mean?” he asked sternly. M’Adam shrugged his shoulders. “There’s mony a slip ‘twixt Cup and lip, that’s a’. I was thinkin’ some mischance might come to him.”

The Master’s eyes flashed dangerously. He recalled the many rumors he had heard, and the attempt on the old dog early in the year.

“I canna think ony one would be coward enough to murder him,” he said, drawing himself up.

M’Adam lent forward. There was a nasty glitter in his eye, and his face was all a-tremble.

“Ye’d no think ony one ‘d be cooard enough to set the son to murder the father. Yet some one did,—set the lad on to ‘sassinate me. He failed at me, and next, I suppose, he’ll try at Wullie!” There was a flush on the sallow face, and a vindictive ring in the thin voice. “One way or t’ither, fair or foul, Wullie or me, am or baith, has got to go afore Cup Day, eh, James Moore! eh?”

The Master put his hand on the latch of the gate, “That’ll do, M’Adam,” he said. “I’ll stop to hear no more, else I might get angry we’ yo’. Noo git off this gate, yo’re trespassin’ as ‘tis.

He shook the gate. M’Adam tumbled off, and went sprawling into the sheep clustered below. Picking himself up, he dashed on through the flock, waving his arms, kicking fantastically, and scattering confusion everywhere.

“Just wait till I’m thro’ wi’ ‘em, will yo’?” shouted the Master, seeing the danger.

It was a request which, according to the etiquette of shepherding, one man was bound to grant another. But M’Adam rushed on regardless, dancing and gesticulating. Save for the lightning vigilance of Owd Bob, the flock must have broken.

“I think yo’ might ha’ waited!” remonstrated the Master, as the little man burst his way through.

“Noo, I’ve forgot somethin’!” the other cried, and back he started as he had gone.

It was more than human nature could tolerate.

“Bob, keep him off!”

A flash of teeth; a blaze of gray eyes; and~ the old dog had leapt forward to oppose the little man’s advance.

“Shift oot o’ ma light!” cried he, striving to dash past.

“Hold him, lad!”

And hold him the old dog did, while his master opened the gate and put the flock through, the opponents dodging in front of one another like opposing three-quarter-backs at the Rugby game.

“Oot o’ ma path, or I’ll strike!” shouted the little man in a fury, as the last sheep passed through the gate.

“I’d not,” warned the Master.

“But I will!” yelled M’Adam; and, darting forward as the gate swung to, struck furiously at his opponent.

He missed, and the gray dog charged at him like a mail-train.

“Hi! James Moore—” but over he went like a toppled wheelbarrow, while the old dog turned again, raced at the gate, took it magnificently in his stride, and galloped up the lane after his master.

At M’Adam’s yell, James Moore had turned.

“Served yo’ properly!” he called back. “He’ll lam ye yet it’s not wise to tamper wi’ a gray dog or his sheep. Not the first time he’s downed ye, I’m thinkin’!”

The little man raised himself painfully to his elbow and crawled toward the gate. The Master, up the lane, could hear him cursing as he dragged himself. Another moment, and a head was poked through the bars of the gate, and a devilish

Comments (0)