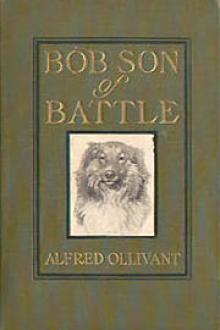

Bob, Son of Battle, Alfred Ollivant [graded readers txt] 📗

- Author: Alfred Ollivant

- Performer: -

Book online «Bob, Son of Battle, Alfred Ollivant [graded readers txt] 📗». Author Alfred Ollivant

He was all a-shake, bobbing up and down like a stopper in a soda-water bottle, and almost sobbing.

“Ha’ ye no wranged me enough wi’ oo that? Ye lang-leggit liar, wi’ yer skulkin murderin’ tyke!” he cried. “Ye say it’s Wullie. Where’s yer proof? “—and he snapped his fingers in the other’s face.

The Master was now as calm as his foe was passionate. “Where?” he replied sternly; why, there!” holding out his right hand. “Yon’s proof enough to hang a hunner’d.” For lying in his broad palm was a little bundle of that damning red hair.

“Where?”

“There!”

“Let’s see it!” The little man bent to look closer.

“There’s for yer proof!” he cried, and spat deliberately down into the other’s naked palm. Then he stood back, facing his enemy in a manner to have done credit to a nobler deed.

James Moore strode forward. It looked as if he was about to make an end of his miserable adversary, so strongly was he moved. His chest heaved, and the blue eyes blazed. But just as one had thought to see him take his foe in the hollow of his hand and crush him, who should come stalking round the corner of the house but the Tailless Tyke?

A droll spectacle he made, laughable even. at that moment. He limped sorely, his head and neck were swathed in bandages, and beneath their ragged fringe the little eyes gleamed out fiery and bloodshot.

Round the corner he came, unaware of strangers; then straightway recognizing his visitors, halted abruptly. His hackles ran up, each individual hair stood on end till his whole body resembled a new-shorn wheat-field; and a snarl, like a rusty brake shoved hard down~ escaped from between his teeth. Then he trotted heavily forward, his head sinking low and lower as he came.

And Owd Bob, eager to take up the gage of battle, advanced, glad and gallant, to meet him. Daintily he picked his way across the. yard, head and tail erect, perfectly self-contained. Only the long gray hair about his neck stood up like the ruff of a lady of the court of Queen Elizabeth.

But the war-worn warriors were not to be allowed their will.

“Wullie, Wullie, wad ye!” cried the little man.

“Bob, lad, coom in!” called the other. Then~ he turned and looked down at the man beside him, contempt flaunting in every feature.

“Well?” he said shortly.

M’Adam’s hands were opening and shuting; his face was quite white beneath the tan; but he spoke calmly.

“I’ll tell ye the whole story, and it’s the truth,” he said slowly. “I was up there the morn “—pointing to the window above—” and I see Wullie crouchin’ down alangside the Stony Bottom. (Ye ken he has the run o’ ma land o’ neets, the same as your dog.) In a minnit I see anither dog squatterin’ alang on your side the Bottom. He creeps up to the sheep on th’ hillside, chases ‘em, and doons one. The sun was risen by then, and I see the dog clear as I see you noo. It was that dog there—I swear it!” His voice rose as he spoke, and he pointed an accusing finger at Owd Bob.

“Noo, Wullie! thinks I. And afore ye could clap yer hands, Wullie was over the Bottom and on to him as he gorged—the bloody-minded murderer! They fought and fought—I could hear the roarin’ a’t where I stood. I watched till I could watch nae langer, and, all in a sweat, I rin doon the stairs and oot. When I got there, there was yer tyke makin’ fu’ split for Kenmuir, and Wullie comin’ up the hill to me. It’s God’s truth, I’m tellin’ ye. Tak’ him hame, James Moore, and let his dinner be an ounce o’ lead. ‘Twill be the best day’s work iver ye done.”

The little man must be lying—lying palpably. Yet he spoke with an earnestness, a seeming belief in his own story, that might have convinced one who knew him less well. But the Master only looked down on him with a great scorn.

“It’s Monday to-day.” he said coldly. “I gie yo’ till Saturday. If yo’ve not done your duty by then—and well you know what ‘tis—I shall come do it for ye. Ony gate, I shall come and see. I’ll remind ye agin o’ Thursday—yo’ll be at the Manor dinner, I suppose. Noo I’ve warned yo’, and you know best whether I’m in earnest or no. Bob, lad!”

He turned away, but turned again.

“I’m sorry for ye, but I’ve ma duty to do— so’ve you. Till Saturday I shall breathe no word to ony soul o’ this business, so that if you see good to put him oot o’ the way wi’oot bother, no one need iver know as hoo Adam M’Adam’s Red Wull was the Black Killer.”

He turned away for the second time. But the little man sprang after him, and clutched him by the arm.

“Look ye here, James Moore!” he cried in thick, shaky, horrible voice. “Ye’re big, I’m sma’; ye’re strang, I’m weak; ye’ve ivery one to your back, I’ve niver a one; you tell your story, and they’ll believe ye—for you gae to church; I’ll tell mine, and they’ll think I lie—for I dinna. But a word in your ear! If iver agin I catch ye on ma land, by—! “—he swore a great oath—” I’ll no spare ye. You ken best if I’m in earnest or no.” And his face was dreadful to see in its hideous determinedness.

THAT night a vague story was whispered In the Sylvester Arms. But Tammas, on being interrogated, pursed his lips and said: “Nay, I’m sworn to say nowt.” Which was the old man’s way of putting that he knew nowt.

On Thursday morning, James Moore and Andrew came down arrayed in all their best. It was the day of the squire’s annual dinner to his tenants.

The two, however, were not allowed to start upon their way until they had undergone a critical inspection by Maggie; for the girl liked her mankind to do honor to Kenmuir on these occasions. So she brushed up Andrew, tied his scarf, saw his boots and hands were clean, and titivated him generally till she had converted the ungainly hobbledehoy into a thoroughly “likely young mon.”

And all the while she was thinking of that other boy for whom on such gala days she had been wont to perform like offices. And her father, marking the tears in her eyes, and mindful of the squire’s mysterious hint, said gently:

“Cheer up, lass. Happen I’ll ha’ news for you the night!”

The girl nodded, and smiled wanly.

“Happen so, dad,” she said. But in her heart she doubted.

Nevertheless it was with a cheerful countenance that, a little later, she stood in the door with wee Anne and Owd Bob and waved the travellers Godspeed; while the golden-haired lassie, fiercely gripping the old dog’s tail with one hand and her sister with the other, screamed them a wordless farewell.

The sun had reached its highest when the two wayfarers passed through the gray portals of the Manor.

In the stately entrance hall, imposing with all the evidences of a long and honorable line, were gathered now the many tenants throughout the wide March Mere Estate. Weather-beaten, rent-paying sons of the soil; most of them native-born, many of them like James Moore, whose fathers had for generations owned and farmed the land they now leased at the hands of the Sylvesters there in the old hail they were assembled, a mighty host. And apart from the others, standing as though in irony beneath the frown of one of those steel-clad warriors who held the door, was little M’Adam, puny always, paltry now, mocking his manhood.

The door at the far end of the hail opened, and the squire entered, beaming on every one.

“Here you are—eh, eh! How are you all? Glad to see ye! Good-day, James! Good-day, Saunderson! Good-day to you all! Bringin’ a friend with me—eh, eh!” and he stood aside to let by his agent, Parson Leggy, and last of all, shy and blushing, a fair-haired young giant.

“If it bain’t David!” was the cry. “Eh, lad, we’s fain to see yo’! And yo’m lookin’ stout, surely!” And they thronged about the boy, shaking him by the hand, and asking him his story.

‘Twas but a simple tale. After his flight on the eventful night he had gone south, drover— ing. He had written to Maggie, and been surprised and hurt to receive no reply. In vain he had waited, and too proud to write again, had remained ignorant of his father’s recovery,, neither caring nor daring to return. Then by mere chance, he had met the squire at the York cattle-show; and that kind man, who knew his story, had eased his fears and obtained from him a promise to return as soon as the term of his engagement had expired. And there he was.

The Dalesmen gathered round the boy, listening to his tale, and in return telling him the home news, and chaffing him about Maggie.

Of all the people present, only one seemed unmoved, and that was M’Adam. When first David had entered he had started forward, a flush of color warming his thin cheeks; but no one had noticed his emotion; and now, back again beneath his armor, he watched the scene, a sour smile playing about his lips.

“I think the lad might ha’ the grace to come and say he’s sorry for ‘temptin’ to murder me. Hooiver “—with a characteristic shrug—” I suppose I’m onraisonahie.”

Then the gong rang out its summons, and the squire led the way into the great dining-hail. At the one end of the long table, heavy with all the solid delicacies of such a feast, he took his seat with the Master of Kenmuir upon his right. At the other end was Parson Leggy. While down the sides the stalwart Dalesmen were arrayed, with M’Adam a little lost figure in the centre.

At first they talked but little, awed like chil.. dren: knives plied, glasses tinkled, the carvers had all their work, only the tongues were at rest. But the squire’s ringing laugh and the parson’s cheery tones soon put them at their ease; and a babel of voices rose and waxed.

Of them all, only M’Adam sat silent. He talked to no man, and you may be sure no one talked to him. His hand crept of tener to his glass than plate, till the sallow face began to flush, and the dim eyes to grow unnaturally bright.

Toward the end of the meal there was loud tapping on the table, calls for silence, and men pushed back their chairs. The squire was on his feet to make his annual speech.

He started by telling them how glad he was to see them there. He made an allusion to Owd Bob and the Shepherds’ Trophy which was heartily applauded. He touched on the Black Killer, and said he had a remedy to propose: that Th’ Owd Un should he set upon the criminal’s track—a suggestion which was received with enthusiasm, while M’Adam’s cackling laugh could be heard high above the rest.

From that he dwelt upon the existing condition of agriculture, the depression in which he attributed to the late Radical Government. He said that now with the Conservatives in office, and a ministry composed of “honorable men and gentlemen,” he felt convinced that things would brighten. The Radicals’ one ambition was to set class against class, landlord against tenant. Well, during the last five hundred years, the Sylvesters had rarely been—he was sorry to have to confess it—good men (laughter and

Comments (0)