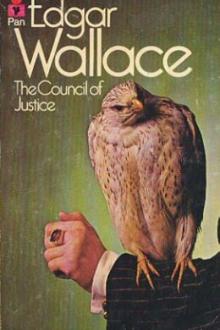

The Council of Justice, Edgar Wallace [english novels to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Book online «The Council of Justice, Edgar Wallace [english novels to read .txt] 📗». Author Edgar Wallace

examination before making any statement.

One unusual feature of the case is understood to be contained in a

letter found in the room accepting, on behalf of an organization known

as the Four Just Men, full responsibility for the killing of the two

foreigners, and another, writes a correspondent, is the extraordinary

structural damage to the room itself. The tenant, the Countess

Slienvitch, had not, up to a late hour last night, been traced.

Superintendent Falmouth, standing in the centre of the room, from

which most traces of the tragedy had been removed, was mainly concerned

with the ‘structural damage’ that The Times so lightly passed

over.

At his feet yawned a great square hole, and beneath, in the empty

flat below, was a heap of plaster and laths, and the debris of

destruction.

‘The curious thing is, and it shows how thorough these men are,’

explained the superintendent to his companion, ‘that the first thing we

found when we got there was a twenty-pound note pinned to the wall with

a brief note in pencil saying that this was to pay the owner of the

property for the damage.’

It may be added that by the express desire of the young man at his

side he dispensed with all ceremony of speech.

Once or twice in speaking, he found himself on the verge of saying,

‘Your Highness’, but the young man was so kindly, and so quickly put

the detective at his ease, that he overcame the feeling of annoyance

that the arrival of the distinguished visitor with the letter from the

commissioner had caused him, and became amiable.

‘Of course, I have an interest in all this,’ said the young man

quietly; ‘these people, for some reason, have decided I am not fit to

encumber the earth—’

‘What have you done to the Red Hundred, sir?’

The young man laughed.

‘Nothing. On the contrary,’ he added with a whimsical smile, ‘I have

helped them.’

The detective remembered that this hereditary Prince of the Escorial

bore a reputation for eccentricity.

With a suddenness which was confusing, the Prince turned with a

smile on his lips.

‘You are thinking of my dreadful reputation?’

‘No, no!’ disclaimed the embarrassed Mr. Falmouth. ‘I—’

‘Oh, yes—I’ve done lots of things,’ said the other with a little

laugh; ‘it’s in the blood—my illustrious cousin—’

‘I assure your Highness,’ said Falmouth impressively, ‘my

reflections were not—er—reflections on yourself—there is a story

that you have dabbled in socialism—but that, of course—’

‘Is perfectly true,’ concluded the Prince calmly. He turned his

attention to the hole in the floor.

‘Have you any theory?’ he asked.

The detective nodded.

It’s more than a theory—it’s knowledge—you see we’ve seen Jessen,

and the threads of the story are all in hand.’

‘What will you do?’

‘Nothing,’ said the detective stolidly; ‘hush up the inquest until

we can lay the Four Just Men by the heels.’

‘And the manner of killing?’

‘That must be kept quiet,’ replied Falmouth emphatically. This

conversation may furnish a clue as to the unprecedented conduct of the

police at the subsequent inquest.

In the little coroner’s court there was accommodation for three

pressmen and some fifty of the general public. Without desiring in any

way to cast suspicion upon the cleanest police force in the world, I

can only state that the jury were remarkably well disciplined, that the

general public found the body of the court so densely packed with

broad-shouldered men that they were unable to obtain admission. As to

the press, the confidential circular had done its work, and the three

shining lights of journalism that occupied the reporters’ desk were

careful to carry out instructions.

The proceedings lasted a very short time, a verdict, ‘…some person

or persons unknown,’ was recorded, and another London mystery was added

(I quote from the Evening News) to the already alarming and

formidable list of unpunished crimes.

Charles Garrett was one of the three journalists admitted to the

inquest, and after it was all over he confronted Falmouth.

‘Look here, Falmouth,’ he said pugnaciously, ‘what’s the racket?’

Falmouth, having reason to know, and to an extent stand in awe of, the

little man, waggled his head darkly.

‘Oh, rot!’ said Charles rudely, ‘don’t be so disgustingly

mysterious—why aren’t we allowed to say these chaps died—?’

‘Have you seen Jessen?’ asked the detective.

‘I have,’ said Charles bitterly, ‘and after what I’ve done for that

man; after I’ve put his big feet on the rungs of culture—’

‘Wouldn’t he speak?’ asked Falmouth innocently.

‘He was as close,’ said Charles sadly, ‘as the inside washer of a

vacuum pump.’

‘H’m!’ the detective was considering. Sooner or later the connection

must occur to Charles, and he was the only man who would be likely to

surprise Jessen’s secret. Better that the journalist should know now.

‘If I were you,’ said Falmouth quietly, ‘I shouldn’t worry Jessen;

you know what he is, and in what capacity he serves the Government.

Come along with me.’

He did not speak a word in reply to the questions Charles put until

they passed through the showy portals of Carlby Mansions and a lift had

deposited them at the door of the flat.

Falmouth opened the door with a key, and Charles went into the flat

at his heels.

He saw the hole in the floor.

‘This wasn’t mentioned at the inquest,’ he said; ‘but what’s this to

do with Jessen?’

He looked up at the detective in perplexity, then a light broke upon

him and he whistled.

‘Well, I’m—’ he said, then he added softly—‘But what does the

Government say to this?’

‘The Government,’ said Falmouth in his best official manner,

smoothing the nap of his hat the while—‘the Government regard the

circumstances as unusual, but they have accepted the situation with

great philosophy.’

That night Mr. Long (or Jessen) reappeared at the Guild as though

nothing whatever had happened, and addressed his audience for half an

hour on the subject of ‘Do burglars make good caretakers?’

CHAPTER VIII. An Incident in the Fight

From what secret place in the metropolis the Woman of Gratz

reorganized her forces we shall never know; whence came her strength of

purpose and her unbounded energy we can guess. With Starque’s death she

became virtually and actually the leader of the Red Hundred, and from

every corner of Europe came reinforcements of men and money to

strengthen her hand and to re-establish the shaking prestige of the

most powerful association that Anarchism had ever known.

Great Britain had ever been immune from the active operations of the

anarchist. It had been the sanctuary of the revolutionary for

centuries, and Anarchism had hesitated to jeopardize the security of

refugees by carrying on its propaganda on British soil. That the

extremists of the movement had chafed under the restriction is well

known, and when the Woman of Gratz openly declared war on England, she

was acclaimed enthusiastically.

Then followed perhaps the most extraordinary duels that the world

had ever seen. Two powerful bodies, both outside the pale of the law,

fought rapidly, mercilessly, asking no quarter and giving none. And the

eerie thing about it all was, that no man saw the agents of either of

the combatants. It was as though two spirit forces were engaged in some

titanic combat. The police were almost helpless. The fight against the

Red Hundred was carried on, almost single-handedly, by the Four Just

Men, or, to give them the title with which they signed their famous

proclamation, ‘The Council of Justice’…

Since the days of the Fenian scare, London had never lived under the

terror that the Red Hundred inspired. Never a day passed but

preparations for some outrage were discovered, the most appalling of

which was the attempt on the Tube Railway. If I refer to them as

‘attempts’, and if the repetition of that word wearies the reader, it

is because, thanks to the extraordinary vigilance of the Council of

Justice, they were no more.

‘This sort of thing cannot go on,’ said the Home Secretary

petulantly at a meeting of the heads of the police. ‘Here we have

admittedly the finest police force in the world, and we must needs be

under obligation to men for whom warrants exist on a charge of

murder!’

The chief commissioner was sufficiently harassed, and was inclined

to resent the criticism in the minister’s voice.

‘We’ve done everything that can be done, sir,’ he said shortly; ‘if

you think my resignation would help you out of the difficulty–-‘

‘Now for heaven’s sake, don’t be a fool,’ pleaded the Home

Secretary, in his best unparliamentary manner. ‘Cannot you

see––’

‘I can see that no harm has been done so far,’ said the commissioner

doggedly; then he burst forth:

‘Look here, sir! our people have very often to employ characters a

jolly sight worse than the Four Just Men—if we don’t employ them we

exploit them. Mean little sneak-thieves, “narks” they call ‘em, old lags,

burglars—and once or twice something worse. We are here to protect

the public; so long as the public is being protected, nobody can kick–’

‘But it is not you who are protecting the public—you get your

information—

‘From the Council of Justice, that is so; but where it comes from

doesn’t matter. Now, listen to me, sir.’

He was very earnest and emphasized his remarks with little raps on

the desk.

‘Get the Prince of the Escorial out of the country,’ he said

seriously. ‘I’ve got information that the Reds are after his blood. No,

I haven’t been warned by the Just Men, that’s the queer part about it.

I’ve got it straight from a man who’s selling me information. I shall

see him tonight if they haven’t butchered him.’

‘But the Prince is our guest.’

‘He’s been here too long,’ said the practical and unsentimental

commissioner; ‘let him go back to Spain—he’s to be married in a month;

let him go home and buy his trousseau or whatever he buys.’

‘Is that a confession that you cannot safeguard him?’

The commissioner looked vexed.

‘I could safeguard a child of six or a staid gentleman of sixty, but

I cannot be responsible for a young man who insists on seeing London

without a guide, who takes solitary motor-car drives, and refuses to

give us any information beforehand as to his plans for the day—or if

he does, breaks them!’

The minister was pacing the apartment with his head bent in

thought.

‘As to the Prince of the Escorial,’ he said presently, ‘advice has

already been conveyed to his Highness—from the highest quarter—to

make his departure at an early date. Tonight, indeed, is his last night

in London.’

The Commissioner of Police made an extravagant demonstration of

relief.

‘He’s going to the Auditorium tonight,’ he said, rising. He spoke a

little pityingly, and, indeed, the Auditorium, although a very

first-class music hall, had a slight reputation. ‘I shall have a dozen

men in the house and we’ll have his motor-car at the stage door at the

end of the show.’

That night his Highness arrived promptly at eight o’clock and stood

chatting pleasantly with the bare-headed manager in the vestibule. Then

he went alone to his box and sat down in the shadow of the red velvet

curtain.

Punctually at eight there arrived two other gentlemen, also in

evening dress. Antonio Selleni was one and Karl Ollmanns was the other.

They were both young men, and before they left the motor-car they

completed their arrangement.

‘You

Comments (0)