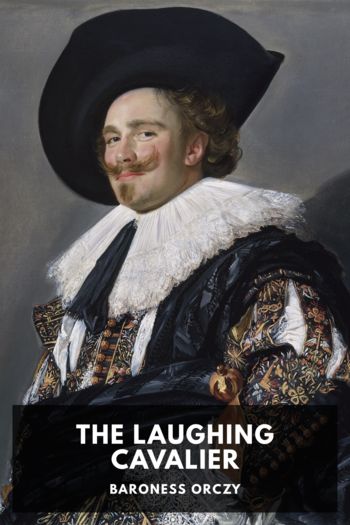

The Laughing Cavalier, Baroness Orczy [the beginning after the end read novel TXT] 📗

- Author: Baroness Orczy

Book online «The Laughing Cavalier, Baroness Orczy [the beginning after the end read novel TXT] 📗». Author Baroness Orczy

New hope rose in the Lord of Stoutenburg’s heart, giving vigour to his arm. Now he heard the sound of running footsteps behind him; Jan was coming to his aid and there were others; Nicolaes no doubt and Heemskerk.

“My lord! my lord!” cried Jan, horrified at what he saw. He had heard the clang of steel against steel and had caught up the first sword that came to his hand. His calls and those of Stoutenburg as well as the more lusty ones of Diogenes reached the ears of Beresteyn, who with his friend Heemskerk was making a final survey of the molens, to search for compromising papers that might have been left about. They too heard the cries and the clash of steel; they ran down the steps of the molens, only to meet Jan who was hurrying toward the hut with all his might.

“I think my lord is being attacked,” shouted Jan as he flew past, “and the jongejuffrouw is still in the hut.”

These last words dissipated Nicolaes Beresteyn’s sudden thoughts of cowardice. He too snatched up a sword and followed by Heemskerk he ran in Jan’s wake.

The stranger, so lately a prisoner condemned to hang, was in the doorway of the hut, with his back to it, his sword in his left hand keeping my Lord of Stoutenburg at arm’s length. Jan, Nicolaes and Heemskerk were on him in a trice.

“Two, three, how many of you?” queried Diogenes with a laugh, as with smart riposte he met the three blades which suddenly flashed out against him. “Ah, Mynheer Beresteyn, my good Jan, I little thought that I would see you again.”

“Let me pass, man,” cried Beresteyn, “I must to my sister.”

“Not yet, friend,” he replied, “till I know what your intentions are.”

For one instant Beresteyn appeared to hesitate. The kindly sentiment which had prompted him awhile ago to speak sympathetic words to a condemned man who had taken so much guilt upon his shoulders, still fought in his heart against his hatred for the man himself. Since that tragic moment at the foot of the gallows which had softened his mood, Beresteyn had learnt that it was this man who had betrayed him and his friends to the Stadtholder, and guessed that it was Gilda who had instigated or bribed him into that betrayal. And now the present position seemed to bring vividly before his mind the picture of that afternoon in the Lame Cow at Haarlem, when the knave whom he had paid to keep Gilda safely out of the way was bargaining with his father to bring her back to him.

All the hatred of the past few days—momentarily lulled in the face of a tragedy—rose up once more with renewed intensity in his heart. Here was the man who had betrayed him, and who, triumphant, was about to take Gilda back to Haarlem and receive a fortune for his reward.

While Heemskerk, doubtful and hesitating, marvelled if ’twere wise to take up Stoutenburg’s private quarrels rather than follow his other friends to Scheveningen where safety lay, Jan and Beresteyn vigorously aided by Stoutenburg made a concerted attack upon the knave.

But it seemed as easy for Bucephalus to deal with three blades as with one: now it appeared to have three tongues of pale grey flame that flashed hither and thither—backwards, forwards, left, right, above, below, parry, riposte, an occasional thrust, and always quietly on guard.

Diogenes was in his greatest humour laughing and shouting with glee. To anyone less blind with excitement than were these men it would soon have been clear that he was shouting for the sole purpose of making a noise, a noise louder than the hammerings, the jinglings, the knocking that was going on at the back of the hut.

To right and left of the front of the small building a high wooden paling ran for a distance of an hundred paces or so enclosing a rough yard with a shed in the rear. It was impossible to see over the palings what was going on behind them and so loudly did the philosopher shout and laugh, and so vigorously did steel strike against steel that it was equally impossible to perceive the sounds that came from there.

But suddenly Stoutenburg was on the alert: something had caught his ear, a sound that rose above the din that was going on in the doorway … a woman’s piercing shriek. Even the clang of steel could not drown it, nor the lusty shouts of the fighting philosopher.

For a second he strained his ear to listen. It seemed as if invisible hands were suddenly tearing down the wooden palisade that hid the rear of the small building from his view; before his mental vision a whole picture rose to sight. A window at the back of the hut broken in, Gilda carried away by the friends of this accursed adventurer—Jan had said that two came to his aid at the foot of the gallows—Maria screaming, the sledge in wait, the horses ready to start.

“My God, I had not thought of that,” he cried, “Jan! Nicolaes! in Heaven’s name! Gilda! After me! quick!”

And then he starts

Comments (0)