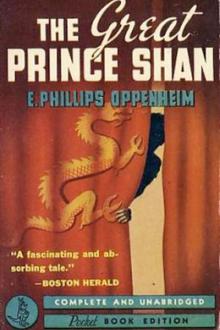

The Great Prince Shan, E. Phillips Oppenheim [positive books to read TXT] 📗

- Author: E. Phillips Oppenheim

- Performer: -

Book online «The Great Prince Shan, E. Phillips Oppenheim [positive books to read TXT] 📗». Author E. Phillips Oppenheim

"You know what our poet says, Nita," he reminded her. "'Love is like the rustling of the wind in the almond trees before dawn.' We cannot command it. It comes to us or leaves us without reason."

She looked across the auditorium once more and spoke with her head turned away from her companion.

"There is no one in the East," she said, "because those who write me weekly send news of my lord's doings. There is no one in the East, because there they give the body who know nothing of the soul. And so my Prince is safe amongst them. But here—these western women have other gifts. Is that she, master of my life and soul?"

"I met her this evening for the first time," he replied.

She laughed drearily.

"Eyes may meet in the street without speech, a glance may burn its way into the soul. Once I thought that I might love again, because a stranger smiled at me in the Bois, and he had grey eyes, and that look about his mouth which a woman craves for. He passed on, and I forgot. You see, my lord was still there.—So this is the woman."

"Who knows?" he answered.

Immelan came into the box a little abruptly. There was a cloud upon his face which he did his best to conceal. Almost simultaneously, a messenger from behind the scenes arrived for Nita. She rose to her feet and wrapped her green cloak closely around her lissom figure.

"In a quarter of an hour," she said, "I have to appear again. It is to be good-night, then?"

She raised her eyes to his, and for a moment the appeal which knows no nationality shone out of their velvety depths. She stood before him simply, like a slave who pleads. Not a muscle of Prince Shan's face moved.

"It is to be good-night, Nita," he answered calmly.

Her head drooped, and she passed out. She had the air of a flower whose petals have been bruised. Immelan looked after her curiously, almost compassionately.

"It is finished, then, with the little one, Prince?" he enquired.

"It is finished," was the calm reply.

Immelan stroked his short moustache thoughtfully.

"Is it wise?" he ventured. "She has been faithful and assiduous. She knows many things."

Prince Shan's eyes were filled with mild wonder.

"She has had some years of my occasional companionship," he said. "It is surely as much as she could hope for or expect. We are not like you Westerners, Immelan," he went on. "Our women are the creatures of our will. We call them, or we send them away. They know that, and they are prepared."

"It seems a little brutal," Immelan muttered.

"You prefer your method?" his companion asked. "Yet you practise deceit. Your fancy wanders, and you lie about it. You lose your dignity, my friend. No woman is worth a man's lie."

Immelan was leaning back in his chair, gazing steadfastly across the crowded theatre.

"Your principles," he said, "are suited to your own womenkind. La Belle Nita has become westernised. Are you sure that she accepts the situation as she would if she dwelt with you in Pekin?"

"I am her master," Prince Shan declared calmly. "I have made no promises that I have not fulfilled."

"The promise between a man and a woman is an unspoken one," Immelan persisted. "You have not been in Europe for five months. All that time she has awaited you."

"Something else has happened," Prince Shan said deliberately.

"Since your arrival in London?"

"Since my arrival in London, since I stepped out of my ship last night."

Immelan was frankly incredulous.

"You mean Lady Maggie Trent?"

"Certainly! I have always felt that some day or other my thoughts would turn towards one of these strange, western women. That time has come. Lady Maggie possesses those charms which come from the brain, yet which appeal more deeply than any other to the subtle desires of the poet, the man of letters and the philosopher. She is very wonderful, Immelan. I thank you for your introduction."

Immelan ceased to caress his moustache. He leaned back in his chair and gazed at his companion. For many years he and the Prince had been associates, yet at that moment he felt that he had not even begun to understand him.

"But you forget, Prince," he said, "that Lady Maggie and her friends are in the opposite camp. When our agreement is concluded and known to the world, she will look upon you as an enemy."

"As yet," Prince Shan answered calmly, "our agreement is not concluded."

Immelan's face darkened. Nothing but his awe of the man with whom he sat prevented an expression of anger.

"But, Prince," he expostulated, "apart from political considerations, you cannot really imagine that anything would be possible between you and Lady Maggie?"

"Why not?" was the cool reply.

"Lady Maggie is of the English nobility," Immelan pointed out. "Neither she nor her friends would be in the least likely to consider anything in the nature of a morganatic alliance."

"It would not be necessary," Prince Shan declared. "It is in my mind to offer her marriage."

Immelan dropped the cigarette case which he had just drawn from his pocket. He gazed at his companion in blank and unaffected astonishment.

"Marriage?" he muttered. "You are not serious!"

"I am entirely serious," the Prince insisted. "I can understand your amazement, Immelan. When the idea first came into my mind, I tore at it as I would at a weed. But we who have studied in the West have learnt certain great truths which our own philosophers have sometimes missed. All that is best of life and of death our own prophets have taught us. From them we have learnt fortitude and chastity: devotion to our country and singleness of purpose. Over here, though, one has also learnt something. Nobility is of the soul. A Prince of the Shans must seek not for the body but for the spirit of the woman who shall be his mate. If their spirits meet on equal terms, then she may even share the throne of his life."

Immelan was speechless. There was something final and convincing in his companion's measured words. His own protest, when at last he spoke, sounded paltry.

"But supposing it is true that she is already engaged to Lord Dorminster?"

Prince Shan smiled very quietly.

"That," he said, "can easily be disposed of."

"But do you seriously believe that you would be able to induce her to return with you to Pekin?" Immelan persisted.

At that moment it chanced that Maggie turned her head and looked across at the two men. Prince Shan leaned a little forward to meet her gaze. His face was expressionless. The lines of his mouth were calm and restful, yet in his eyes there glowed for a single moment the fire of a man who looks upon the thing he covets.

"I seriously believe it," he answered under his breath.

Maggie leaned back in her chair with a little sigh of content. The scarlet-coated waiter had just removed their tea tray, a pleasant breeze was rustling through the leaves of the trees under which she and Prince Shan were seated. From the distance came the low strains of a military band. Everywhere on the lawns and along the paths men and women were promenading.

"Confess that this is better than Rumpelmayer's or the Ritz," she murmured lazily.

"It is better," he admitted. "It is a very wonderful place."

"You have nothing like it in China?" she asked him.

"It would not be possible," he answered. "Democracy there is confined to politics. In other respects, our class prejudices are far more rigid than yours. But then I see a great change in this country since I was here as a student."

"You have lost your affection for it, perhaps?" she ventured, looking at him through half-closed eyes.

"On the contrary," he assured her, "my gratitude towards her was never so great as at this moment. Your country has given me nothing I prize so much, Lady Maggie, as my knowledge of you."

She looked away from his very earnest eyes, and the light retort died away upon her lips. The men and women whom she watched so steadfastly seemed like puppets, the flowers artificial, the music unreal. Already she was beginning to resent the influence which he was establishing over her. The art of badinage in which she was so proficient stood her in no stead. Words, even the power of light speech, had deserted her.

"Tell me about the changes that you see," she asked.

"Perhaps," he replied, after a moment's hesitation, "it is because I am an occasional visitor that differences seem so marked to me, but look at the tables there. That is the Duke of Illinton, is it not? At the next table, the man in the strange clothes and uncomfortable hat—it seems to me that I have seen him somewhere under different circumstances."

Maggie nodded.

"Life is a terrible hotchpotch nowadays," she admitted. "After the war, our gentry and aristocracy who were not wealthy were taxed out of existence. The profiteers, and the men who had made fortunes during the war, took their place. It has made the country prosperous but less picturesque."

"You put things very clearly," he said. "To-day in England is certainly the day of the shopkeeper's triumph. Wealth is a great thing, but it is great only for what it leads to. I think your philosopher of the streets, your new school of politicians, have alike forgotten that."

"You have lost sympathy with England, have you not, Prince Shan?" Maggie asked him.

He turned towards her, a faint but kindly smile upon his lips, a light in his eyes which she did not altogether understand.

"Lady Maggie," he said quietly, "they tell me that you are interested in the political side of my visit to this country."

"Who tells you that?" she demanded. "What have I to do with politics?"

"You have been gifted with great intelligence," he continued, "and you are the confidante of your connection, Lord Dorminster. Lord Dorminster is one of those few Englishmen who realise the ill direction of the destinies of this country. You would like to help him in his present very strenuous efforts to ascertain the truth as to certain movements directed against the British Empire. That is so, is it not?"

"In plain words, you are accusing me of being a spy."

"Ah, no!" he protested gently. "No one can be a spy in one's own country. You are within your rights as a patriot in seeking to discover whatever may be useful knowledge to the English Government. That, I fear, is one reason for your kindness to me, Lady Maggie. I trust that it is not the only reason."

She knew better than to make the mistake of denial. After all, it was an absurdly unequal contest.

"It is not the only reason," she assured him, a little tremulously.

"I am glad. One word more upon this subject, and we speak of other things. Please, Lady Maggie, do not stoop to be hopelessly obvious in these efforts of yours. If I drop a pocketbook, believe me there will be nothing in it to interest you. If I speak with Immelan or any other, save in the secrecy of my chamber, there will be nothing which it will be worth your while to overhear. If Lord Dorminster should decide to adopt buccaneering expedients and kidnap me, the attempt would probably fail; and if it succeeded, it would in the end profit you nothing. As you say over here, for your sake, Lady Maggie, I will lay the cards upon the table. I am discussing with Oscar Immelan, and indirectly with an emissary from Russia, a certain scheme which, if carried out, would certainly be harmful to this country. I shall decide for or against that scheme entirely as it seems to me that it will be for the good or evil of my own country. Nothing will change my purpose in that. In your heart you know that nothing should change it. But I bring to the deliberations upon which we are engaged a new sentiment

Comments (0)