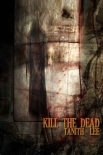

Kill the Dead, Tanith Lee [a court of thorns and roses ebook free .TXT] 📗

- Author: Tanith Lee

Book online «Kill the Dead, Tanith Lee [a court of thorns and roses ebook free .TXT] 📗». Author Tanith Lee

WhenMyal saw the red spirit of the fire rising in a thin streamer from the fortressover the marsh, he picked up a sharp stone from the wayside. But something hadgone wrong. Something always went wrong.

“Ciddey,”he said to the ground.

“That’syour reason, is it?” said the King of Swords.

Myallooked at the king’s boots.

“Shewas very young to die,” Myal said sentimentally. Tears ran out of his eyes. Aseach tear formed it blinded him, and then his sight returned as the dropsdropped straight from the sockets onto the turf. One hit the upturned face of aflower. He could imagine it thinking: Ah! Now I have to contend with saltrain.

“Ifyou’d just left them alone,” Myal said. “She put her shoes on the bank. Shefell back in the water. I tried to get to her, but when I got her out she wasdead.”

Heabandoned himself once more to the fever. He lay, wrapped in misery, waitingfor his consciousness mercifully to go out again. Then King Death was shakinghim. Or seemed to be. The horse had stopped.

“What did yousay?”

“WhatdidI say? Don’t know. You sure I said anything? Maybe just a delirious babble. Youshouldn’t take me too seriously–”

“CiddeySoban. Are you telling me she’s dead?”

“Oh,”Myal yawned. Fresh tears dropped from his eyes. “She drowned herself. It wasyour fault, you damned bastard.”

Butsomething about Dro’s voice, though quite flat, quite expressionless, broughtMyal to the realisation that of course the Ghost-Killer could not have knowntill now about Ciddey. It would have been stupid, after all, to slaughter a manfor a crime he was unaware of having committed.

“Withher sister gone, she had nothing left to live for,” Myal explained.

Drostood, looking away into the spaces of the morning. By twisting his head, Myalcould see him, but it was too much of an effort to retain this position.Eventually Dro said,

“I’mglad for your sake your music isn’t as trite as your dialogue.”

Thehorse began to move again.

Myalsang the song he had made for Ciddey Soban, quietly, to the ground, until hefainted.

Thehostelry was one of seven, but the only such place in the river village run bypriests. The religious building stood off to one side, a whitewashed tower andwooden belfry piled on top of it. The hostel itself stood within a compound, asingle lone story of old brick. The priests came through a wicket gate into thecompound to draw water at the well. Olive trees clawed in over the wall. Therewas a smell of the oil press, and of horses. Dro had hired the horse and theblanket from the priests. They were the only hospitalers in the district whowould take in a sick man and care for him. Dro had been down at first light andfound this out. And even the priests wanted paying. As he came through the dawnvillage and saw them, busy in their gardens and orchards, fishing in a pool,scurrying about with washing and baking, horses and dogs and cages of fowl, hewondered when, if ever, they made time to pray.

Whenhe got back to the fortress, leading the horse for Myal, Myal was obviously toosick to travel over the meadow and the causeway and along the village street.

Itwas a sort of fever Dro had seen before, coming and going in tides. He waitedfor the next low tide, then hauled Myal into the meadow and shovelled him onthe horse. It was almost noon by then.

Dro’splan had been straightforward. To offload the musician on the priests withenough cash to see ailment and convalescence out. That cancelled all guilts,real or invented; Dro could return to his interrupted journey. That was theoriginal plan. Myal’s news altered things. If it were true. A delirious manmight conjure innumerable dreams, believing each and all of them. But that wasan insufficient blind. The sense in Parl Dro which judged such things hadalready credited the death of Ciddey Soban. Her death, and the ominous lacunawhich followed it: the fact his premonitions had foreshadowed.

Theholy brothers had a stretcher ready at the compound gate. Three of them liftedMyal and laid him on the stretcher and carried him into the single-storyhostel.

Drostood outside the open door, looking through into a room divided by woodenscreens and shafts of sunlight. Bed frames were stacked in a corner. One bedhad been prepared.

Thecolour of the order was cream, the same colour as the faded whitewashed walls.Everything blended, brick and linen and men, into a positively supernalluminescence. Myal might come to and think himself in some bizarre afterlifepeopled by ugly angels.

Oneof the angels glided up to the man in black.

“Anact of laudable charity, my son,” said the priest, who was far younger thanDro. “To bring in the sick traveller and to pay for his lodging. Rest assured,your piety will not go unnoticed.”

“Really?I thought I’d been fairly circumspect.”

Thepriest smiled seriously.

“Ithink you mentioned moving on today. We might be able to come to somearrangement about a horse. Generally, of course, we don’t buy and sell, but I’msure we could agree on a price. Seeing your–er–your difficulty.”

“Whatdifficulty is that?”

Thepriest stared at him.

“Youraffliction.”

“Ohdear,” said Dro, “have I been afflicted?”

“Yourleg. I meant your lameness.”

“Ohdear,” said Dro, “you meant my lameness.”

Thepriest went on staring, suddenly aware his point was being wilfully missed.

Comments (0)