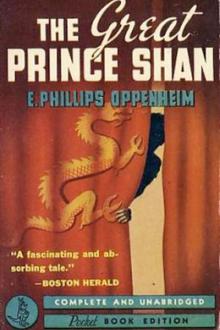

The Great Prince Shan, E. Phillips Oppenheim [positive books to read TXT] 📗

- Author: E. Phillips Oppenheim

- Performer: -

Book online «The Great Prince Shan, E. Phillips Oppenheim [positive books to read TXT] 📗». Author E. Phillips Oppenheim

Nigel assented cautiously.

"I suppose it is an open secret amongst a few of us," he observed. "You have been running an unofficial secret service of your own."

"Precisely! I have had a few agents at work for over a year, and when I have finished decoding this last dispatch, I shall have evidence which will prove beyond a doubt that we are on the threshold of terrible events. The worst of it is—well, we have been found out."

"What do you mean?" Nigel asked quickly.

His uncle's sensitive lips quivered.

"You knew Sidwell?"

"Quite well."

"Sidwell was found stabbed to the heart in a café in Petrograd, three weeks ago," Lord Dorminster announced. "An official report of the enquiry into his death informs his relatives that his death was due to a quarrel with some Russian sailors over one of the women of the quarter where he was found."

"Horrible!" Nigel muttered.

"Sidwell was one of those unnatural people, as you know," Lord Dorminster went on, "who never touched wine or spirits and who hated women. To continue. Atcheson was a friend of yours, wasn't he?"

"Of course! He was at Eton with me. It was I who first brought him here to dine. Don't tell me that anything has happened to Jim Atcheson!"

"This dispatch is from him," Lord Dorminster replied, indicating the pile of manuscript upon the table,—"a dispatch which came into my hands in a most marvellous fashion. He died last week in a nursing home in—well, let us say a foreign capital. The professor in charge of the hospital sends a long report as to the unhappy disease from which he suffered. As a matter of fact, he was poisoned."

Nigel Kingley had been a soldier in his youth and he was a brave man. Nevertheless, the horror of these things struck a cold chill to his heart. He seemed suddenly to be looking into the faces of spectres, to hear the birth of the winds of destruction.

"That is all I have to say to you for the moment," his uncle concluded gravely. "In an hour I shall have finished decoding this dispatch, and I propose then to take you into my entire confidence. In the meantime, I want you to go and talk for a few minutes to the cleverest woman in England, the woman who, in the face of a whole army of policemen and detectives, crossed the North Sea yesterday afternoon with this in her pocket."

"You don't mean Maggie?" Nigel exclaimed eagerly.

His uncle nodded.

"You will find her in the boudoir," he said. "I told her that you were coming. In an hour's time, return here."

Lord Dorminster rose to his feet as his nephew turned to depart. He laid his hand upon the latter's shoulder, and Nigel always remembered the grave kindliness of his tone and expression.

"Nigel," he sighed, "I am afraid I shall be putting upon your shoulders a terrible burden, but there is no one else to whom I can turn."

"There is no one else to whom you ought to turn, sir," the young man replied simply. "I shall be back in an hour."

Lady Maggie Trent, a stepdaughter of the Earl of Dorminster, was one of those young women who had baffled description for some years before she had commenced to take life seriously. She was neither fair nor dark, petite nor tall. No one could ever have called her nondescript, or have extolled any particular grace of form or feature. Her complexion had defied the ravages of sun and wind and that moderate indulgence in cigarettes and cocktails which the youth of her day affected. Her nose was inclined to be retroussé, her mouth tender but impudent, her grey eyes mostly veiled in expression but capable of wonderful changes. She was curled up in a chair when Nigel entered, immersed in a fashion paper. She held out her left hand, which he raised to his lips.

"Well, Nigel, dear," she exclaimed, "what do you think of my new profession?"

"I hate it," he answered frankly.

She sighed and laid down the fashion paper resignedly.

"You always did object to a woman doing anything in the least useful. Do you realise that if anything in the world can save this stupid old country, I have done it?"

"I realise that you've been running hideous risks," he replied.

She looked at him petulantly.

"What of it?" she demanded. "We all run risks when we do anything worth while."

"Not quite the sort that you have been facing."

She smiled thoughtfully.

"Do you know exactly where I have been?" she asked.

"No idea," he confessed. "What my uncle has just told me was a complete revelation, so far as I was concerned. I believed, with the rest of the world, what the newspapers announced—that you were visiting Japan and China, and afterwards the South Sea Islands, with the Wendercombes."

She smiled.

"Dad wanted to tell you," she said, "but it was I who made him promise not to. I was afraid you would be disagreeable about it. We arranged it all with the Wendercombes, but as a matter of fact I did not even start with them. For the last eight months, I have been living part of the time in Berlin and part of the time in a country house near the Black Forest."

"Alone?"

"Not a bit of it! I have been governess to the two daughters of Herr Essendorf."

"Essendorf, the President of the German Republic?"

Lady Maggie nodded.

"He isn't a bit like his pictures. He is a huge fat man and he eats a great deal too much. Oh, the horror of those meals!" she added, with a little shudder. "Think of me, dear Nigel, who never eat more than an omelette and some fruit for luncheon, compelled to sit down every day to a mittagessen! I wonder I have any digestion left at all."

"Do you mean that you were there under your own name?" he asked incredulously.

She shook her head.

"I secured some perfectly good testimonials before I left," she said. "They referred to a Miss Brown, the daughter of Prebendary Brown. I was Miss Brown."

"Great Heavens!" Nigel muttered under his breath. "You heard about Atcheson?"

She nodded.

"Poor fellow, they got him all right. You talk about thrills, Nigel," she went on. "Do you know that the last night before I left for my vacation, I actually heard that fat old Essendorf chuckling with his wife about how his clever police had laid an English spy by the heels, and telling her, also, of the papers which they had discovered and handed over. All the time the real dispatch, written by Atcheson when he was dying, was sewn into my corsets. How's that for an exciting situation?"

"It's a man's job, anyhow," Nigel declared.

She shrugged her shoulders and abandoned the personal side of the subject.

"Have you been in Germany lately, Nigel?" she enquired.

"Not for many years," he answered.

She stretched herself out upon the couch and lit a cigarette.

"The Germany of before the war of course I can't remember," she said pensively. "I imagine, however, that there was a sort of instinctive jealous dislike towards England and everything English, simply because England had had a long start in colonisation, commerce and all the rest of it. But the feeling in Germany now, although it is marvellously hidden, is something perfectly amazing. It absolutely vibrates wherever you go. The silence makes it all the more menacing. Soon after I got to Berlin, I bought a copy of the Treaty of Peace and read it. Nigel, was it necessary to have been so bitterly cruel to a beaten enemy?"

"Logically it would seem not," Nigel admitted. "Actually, we cannot put ourselves back into the spirit of those days. You must remember that it was an unprovoked war, a war engineered by Germany for the sheer purposes of aggression. That is why a punitive spirit entered into our subsequent negotiations."

She nodded.

"I expect history will tell us some day," she continued, "that we needed a great statesman of the Beaconsfield type at the Peace table. However, that is all ended. They sowed the seed at Versailles, and I think we are going to reap the harvest."

"After all," Nigel observed thoughtfully, "it is very difficult to see what practical interference there could be with the peace of the world. I can very well believe that the spirit is there, but when it comes to hard facts—well, what can they do? England can never be invaded. The war of 1914 proved that. Besides, Germany now has a representative on the League of Nations. She is bound to toe the line with the rest."

"It is not in Germany alone that we are disliked," Maggie reminded him. "We seem somehow or other to have found our way into the bad books of every country in Europe. Clumsy statesmanship is it, or what?"

"I should attribute it," Nigel replied, "to the passing of our old school of ambassadors. After all, ambassadors are born, not made, and they should be—they very often were—men of rare tact and perceptions. We have no one now to inform us of the prejudices and humours of the nations. We often offend quite unwittingly, and we miss many opportunities of a rapprochement. It is trade, trade, trade and nothing else, the whole of the time, and the men whom we sent to the different Courts to further our commercial interests are not the type to keep us informed of the more subtle and intricate matters which sometimes need adjustment between two countries."

"That may be the explanation of all the bad feeling," Maggie admitted, "and you may be right when you say that any practical move against us is almost impossible. Dad doesn't think so, you know. He is terribly exercised about the coming of Prince Shan."

"I must get him to talk to me," Nigel said. "As a matter of fact, I don't think that we need fear Asiatic intervention over here. Prince Shan is too great a diplomatist to risk his country's new prosperity."

"Prince Shan," Maggie declared, "is the one man in the world I am longing to meet. He was at Oxford with you, wasn't he, Nigel?"

"For one year only. He went from there to Harvard."

"Tell me what he was like," she begged.

"I have only a hazy recollection of him," Nigel confessed. "He was a most brilliant scholar and a fine horseman. I can't remember whether he did anything at games."

"Good-looking?"

"Extraordinarily so. He was very reserved, though, and even in those days he was far more exclusive than our own royal princes. We all thought him clever, but no one dreamed that he would become Asia's great man. I'll tell you all that I can remember about him another time, Maggie. I'm rather curious about that report of Atcheson's. Have you any idea what it is about?"

She shook her head.

"None at all. It is in the old Foreign Office cipher and it looks like gibberish. I only know that the first few lines he transcribed gave dad the jumps."

"I wonder if he has finished it by now."

"He'll send for you when he has. How do you think I am looking, Nigel?"

"Wonderful," he answered, rising to his feet and standing with his elbow upon the mantelpiece, gazing down at her. "But then you are wonderful, aren't you, Maggie? You know I always thought so."

She picked up a mirror from the little bag by her side and scrutinized her features.

"It can't be my face," she decided, turning towards him with a smile. "I must have charm."

"Your face is adorable," he declared.

"Are you going to flirt with me?" she asked, with a faint smile at the corners of her lips. "You always do it so well and so convincingly. And I hate foreigners. They are

Comments (0)