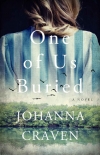

One of Us Buried, Johanna Craven [superbooks4u TXT] 📗

- Author: Johanna Craven

Book online «One of Us Buried, Johanna Craven [superbooks4u TXT] 📗». Author Johanna Craven

Blackwell buttoned his jacket. “Does that surprise you?”

I sat back on the chair, watching a tiny lizard dart under the door. “Sometimes it feels as though God has been forgotten here. At least within the factory walls.”

He ran a comb through his hair and peered into his shaving mirror. “My father was the vicar of our parish,” he told me finally. “So yes. I suppose I am a man of God.”

I felt a faint warmth in my chest. It was the first time he had offered me a scrap of information about who he was.

I stood up and smoothed my skirts. “You go first,” I told him. “I’ll follow.” I was always careful to distance myself from him when the colony was watching. I knew being seen with me would only bring him shame. There was talk of course; whispered at the spinning wheels and hollered over rum at the river. Talk of the factory lass who’d found a bed beneath the roof of an officer. I refused to speak on the subject; refused to give any weight to the rumours. I was afraid that if the gossip came too close, Blackwell might see the error of his ways and send me back to the street.

I pulled the door closed and made my way to the church. And into formation us government men and women went; lining up like children before we were herded into the front pews. Redcoats stood at either end, rifles at the ready. Sunlight blazed through the windows, making dust motes dance above our heads.

Reverend Marsden strode to the pulpit. Though the morning was cold, his cheeks were pink with exertion. His thick fingers curled over the edge of the pulpit as he looked out over the congregation.

I wondered if Maggie would make it into his sermon. A prayer for the departed. An acknowledgement that a crime had been committed. An acknowledgement that Maggie Abbott, a rough-spoken factory lass, had existed.

If anyone was going to speak out against Patrick Owen, I knew it would be the reverend. If there was anything Marsden despised more than the factory lasses, it was the croppies.

Maggie did make it into the sermon that day.

A loose woman, the reverend called her. A harlot. His steely gaze moved along the front row where the factory lasses were sitting. He looked into our eyes as he spoke of the perils of carnal immorality. Of the way a woman’s active sexuality threatened the very order of society. Upset the precious balance of masculine and feminine.

I stared back at him, forcing myself to hold his gaze. The person I was in London would have nodded along with Marsden. Yes, a sinner; a loose woman who deserved all that came to her. But the day I had stepped out of the factory with nowhere to sleep, I had come to see that there was not always a choice.

“The immorality of this colony is a thing you should all be ashamed of,” he said. “The extent of which will become clearer in the coming days and weeks.”

Murmurs rippled through the congregation.

I turned to Hannah, who was sitting beside me. “What do you suppose he means by that?”

She snorted. “Don’t waste your time dwelling on it. When you ever heard anything but drivel come out his mouth?”

“Behave yourselves,” a well-spoken man called down to the convicts.

“You behave yourself,” a young woman snapped back. I hid a smile.

“1 Corinthians 14,” the man boomed down at us, like he was trying to be the very voice of God himself, “it is shameful for a woman to speak in church.”

I returned to the hut before Blackwell, and gathered up my dirty clothes. I took the washboard down to the river and crouched on the edge in the pale winter sun. My boots sank into the muddy bank as I dipped my apron beneath the surface. For a moment, I just held it between my fingers, watching it float ghost-like through the bronze haze of the water.

I scrubbed my clothes along the washboard until my fingers were numb, hanging each piece from a tree; marking the forest with my fleeting scrap of civilisation. The washing helped take my mind off things. Helped take my mind off Maggie Abbott’s blank eyes staring out from within the scrub. Helped me stop wondering what Marsden had meant by revealing the extent of the colony’s immorality.

I bundled my wet clothes into my arms and went back to the hut, draping my shift and petticoats over the table, wet stockings spread out across a chair. I felt as though I was possessing the place, making it my own. Strewn about Blackwell’s hut like this, my clothes felt almost as inconsonant as they had hung up among the wilderness.

His footsteps behind me made me start. I spun around to find him holding out the book he had been reading a few nights earlier. I’d not even heard him come in.

“I’ve finished if you’d care to read it,” he said.

I murmured my thanks. There was something alluring about escaping into a fictitious world for a time. A precious thing here.

He glanced at the ghostly shapes of my washing. “It’s the Lord’s Day. You ought to be resting.” He nodded to the book. “Read it. I think you will enjoy it.”

I took the book and went back to the river. Followed it downstream a few yards to where the mangroves gave way to a battalion of broad trees. There was a chill in the wind, but the sun was struggling through the clouds. I needed to be out in the daylight, not in the endless shadows of the hut.

I opened the book and stared at the first page. The words swam in front of

Comments (0)