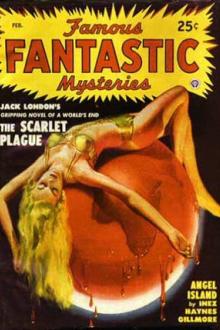

Angel Island, Inez Haynes Gillmore [the two towers ebook txt] 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island, Inez Haynes Gillmore [the two towers ebook txt] 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

a man Ralph is. The only woman you can depend on him to be faithful to

is the one that won’t have him round. I don’t think that bothers Peachy,

though. She adores Julia. If she could fly a little while in the

afternoon - an hour, say - I know it would cure her.”

“Too bad. But, of course, we couldn’t let you girls fly again. Besides,

I doubt very much if, after so many cuttings, your wings would ever grow

big enough. You don’t realize it yourself, perhaps, but you’re much more

healthy and normal without wings.”

“I don’t mind being without them so much myself” - Lulu’s tone was a

little doubtful - “though I think they would help me with Honey-Boy and

Honey-Bunch. Sometimes - .” She did not finish.

“And then,” Honey went on decidedly, “it’s not natural for women to fly.

God never intended them to.”

“It is wonderful,” Lulu said admiringly, “how men know exactly what God

intended.”

Honey roared. “If you’d ever heard the term sarcasm, my dear, I should

think you were slipping something over on me. In point of fact, we don’t

know what God intended. Nobody does. But we know better than you; the

man’s life broadens us.”

“Then I should think - ” Lulu began. But again she did not finish.

“We’re going to make a tower of rocks on the central island of the

lake,” Honey went on. “We’ll drag the stones from the beach - those big,

beauty round ones. When it’s finished, we’re going to cover it with that

vine which has the scarlet, butterfly flowers. Pete says the reflections

in the water will be pretty neat.”

“Really. It sounds charming. And, Honey, Chiquita is so lazy. Little

Junior runs wild. He’s nearly two and she hasn’t made a strip of

clothing for him yet. It’s Frank’s fault, though. He never notices

anything. I really think you men ought to do something about that.”

“And then,” Honey went on. But he stopped. “What’s the use? ” he

muttered under his breath. He subsided, enveloped himself in a cloud of

smoke and listened, half-amused, half-irritated, to Lulu’s pauseless,

squirrel-like chatter.

“My dear,” Frank Merrill said to Chiquita after dinner, “the New Camp is

growing famously. Six months more and you will be living in your new

home. The others - Pete especially - are very much interested in

Recreation Hall. They have just worked out a new scheme for parks and

gardens. It is very interesting, though purely decorative. It offers

many absorbing problems. But, for my own part, I must confess I am more

interested in the library. It will be most gratifying to see all our

books ranged on shelves, classified and catalogued at last. It is a good

little library as amateur libraries go. The others speak again and again

of my foresight during those early months in taking care of the books.

We have many fine books - what people call solid reading - and a really

extraordinary collection of dictionaries. You see, many scholars travel

in the Orient, and they feel they must get up on all kinds of things. I

suggested to-day that we draw up a constitution for Angel Island. For by

the end of twenty years, there will be a third generation growing up

here. And then, the population will increase amazingly. Besides, it

offers many subjects for discussion in our evenings at the Clubhouse,

etc., etc., etc.”

Holding the tired-out little junior in her lap, Chiquita rocked and

fanned herself and napped - and woke - and rocked and fanned herself and

napped again.

“Oh, don’t bore me with any talk about the New Camp,” Clara was saying

to Pete. “I’m not an atom interested in it.”

“But you’re going to live there sometime,” Pete remonstrated, wrinkling

in perplexity his fiery, freckled face.

“Yes, but I don’t feel as if I were. It’s all so far away. And I never

see it. If I had anything to say about it, I might feel differently. But

I haven’t. So please don’t inflict it on me.”

“But it’s the inspiration of building it for you women,” Pete said

gravely, “that makes us men work like slaves. We’re only doing it for

your sake. It is the expression of our love and admiration for you.”

“Oh, slush!” exclaimed Clara flippantly, borrowing from Honey’s

vocabulary. “You’re building it to please yourself. Besides, I don’t

want to be an inspiration for anything.”

“All right, then,” Pete said in an aggrieved tone. “But you are an

inspiration, just the same. It is the chief vocation of women.” He moved

over to the desk and took up a bunch of papers there.

“Oh, are you going to write again this evening?” Clara asked in a burst

of despair.

“Yes.” Pete hesitated. “I thought I’d work for an hour or two and then

I’d go out.”

Clara groaned. “If you leave me another minute of this day, I shall go

mad. I’ve had nothing but housework all the morning and then a little

talk with the girls, late this afternoon. I want something different

now.”

“Well, let me read the third act to you,” Pete offered.

“No, I don’t feel like being read to. I want some excitement.”

Pete sighed, and put his manuscript down.

“All right. Let’s go in swimming. But I’ll have to leave you after an

hour.”

“Are you going to see Peachy?” Clara demanded shrilly.

“No.” Pete’s tone was stern. “I’m going to the Clubhouse.”

“How has everything gone to-day, Billy?” Julia asked, as they sat

looking out to sea.

“Rather well,” Billy answered. “We were all in a working mood and all in

good spirits. We’ve done more to-day than we’ve done in any three days

before. At noon, while we were eating our lunch, I showed them your

plans.”

“You didn’t say - .”

“I didn’t peep. I promised, you know. I let them assume that they were

mine. They went wild over them, threw all kinds of fits. You see, Pete

has a really fine artistic sense that’s going to waste in all these

minor problems of construction and drainage. I flatter myself that I,

too, have some taste. Addington and Honey are both good workmen - that

is, they work steadily under instruction. Merrill’s only an inspired

plumber, of course. Pete and I have been feeling for a long time that we

wanted to do something more creative, more esthetic. This is just the

thing we needed. I’m glad you thought it out; for I was beginning to

grow stale. I sometimes wonder what will happen when the New Camp is

entirely built and there’s nothing else to do.”

Billy’s voice had, in spite of his temperamental optimism, a dull note

of unpleasant anticipation.

“There’ll be plenty to do after that.” Julia smiled reassuringly. “I’m

working on a plan to lay out the entire island. That will take years and

years and years. Even then you’ll need help.”

“That, my beloved,” Billy said, “until the children grow up, is just

what we can’t get - help.”

Julia was silent.

“Julia,” he went on, after an interval, in which neither spoke, “won’t

you marry me? I’m lonely.”

The poignant look - it was almost excruciating now - came into Julia’s

eyes.

“Not now, Billy,” she answered.

“And yet you say you love me!”

The sadness went. Julia’s face became limpid as water, bright as light,

warm as flame. “I love you,” she said. “I love you! I love you!” She

went on reiterating these three words. And with every iteration, the

thrill in her voice seemed to deepen. “And, Billy - .”

“Yes.”

“I’m not quite sure when - but I know I’m going to marry you some time.”

“I’ll wait, then,” Billy promised. “As long as I know you love me, I can

wait until - the imagination of man has not conceived the limit yet.”

“Well, how have you been to-day?” Ralph asked. But before Peachy could

speak, he answered himself in a falsetto voice that parodied her round,

clear accents, I want to fly! I want to fly! I want to fly!” His tone

was not ill-tempered, however; and his look was humorously a

affectionate, as one who has asked the same question many times and

received the same answer.

“I do want to fly, Ralph,” Peachy said listlessly. “Won’t you let me?

Oh, please let my wings grow again?”

Ralph shook his head inflexibly. “Couldn’t do it, my dear. It’s not

womanly. The air is no place for a woman. The earth is her home.”

“That’s not argument,” Peachy asserted haughtily. “That’s statement. Not

that I want to argue the question. My argument is unanswerable. Why did

we have wings, if not to fly. But I don’t want to quarrel - .” Her voice

sank to pleading. “I’d always be here when you came back. You’d never

see me flying. It would not prevent me from doing my duty as your wife

or as Angela’s mother. In fact, I could do it better because it would

make me so happy and well. After a while, I could take Angela with me.

Oh, that would be rapture!” Peachy’s eyes gleamed.

Ralph shook his head. “Couldn’t think of it, my dear. The clouds are no

place for my wife. Besides, I doubt if your wings would ever grow after

the clipping to which we’ve submitted them. Now, put something on, and

I’ll carry you down on the beach.”

“Tell me about the New Camp, and what you did to-day!” Peachy asked,

after an interval in which she visibly struggled for control.

“Oh, Lord, ask anything but that,” Addington exclaimed with a sudden

gust of his old irritability. “I work hard enough all day. When I get

home, I want to talk about something else. It rests me not to think of

it.”

“But, Ralph,” Peachy entreated, “I could help you. I know I could. I

have so many ideas about things. You know Pete says I’m a real artist.

It would interest me so much if you would only talk over the building

plans with me.”

“I don’t know that I am particularly interested in Pete’s opinion of

your abilities,” Addington rejoined coldly. “My dear little girl,” he

went on, palpably striving for patience and gentleness, “there’s nothing

you could do to help me. Women are too impractical. This is a man’s

work, besides. By the way, after we’ve had our little outing, I’ll leave

you with Lulu. Honey and Pete and I are going to meet at the Clubhouse

to work over some plans.”

“All right,” Peachy said. She added, “I guess I won’t go out, after all.

I feel tired. I think I’ll lie down for a while.”

“Anything I can do for you, dear?” Addington asked tenderly as he left.

“Nothing, thank you.” Peachy’s voice was stony. Then suddenly she pulled

herself upright on the couch. “Oh - Ralph - one minute. I want to talk

to you about Angela. Her wings are growing so fast.”

VII“Where’s Peachy?” Julia asked casually the next afternoon.

“I’ve been wondering where she was, too,” Lulu answered. “I think she

must have slept late this morning. I haven’t seen her all day.”

“Is Angela with the children now?” Julia went on.

“I suppose so,” Lulu replied. She lifted herself from the couch. Shading

her hands, she studied the group at the water’s edge. Honey-Boy and

Peterkin were digging wells in the sand. Junior making futile imitative

movements, followed close

Comments (0)