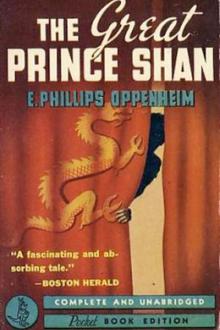

The Great Prince Shan, E. Phillips Oppenheim [positive books to read TXT] 📗

- Author: E. Phillips Oppenheim

- Performer: -

Book online «The Great Prince Shan, E. Phillips Oppenheim [positive books to read TXT] 📗». Author E. Phillips Oppenheim

"It will not be her lack of courage which will keep her in England," Nigel declared.

Prince Shan bowed, with a graceful little gesture of the hands. The subject was finished.

"I shall now, Lord Dorminster," he said, "take advantage of your kindly presence here to speak to you on a very personal matter, only this time it is you who are the central figure, and I who am the dummy."

"I do not follow you," Nigel confessed, with a slight frown.

"I speak in tones of apology," Prince Shan went on, "but you must remember that I am one of reflective disposition; Nature has endowed me with some of the gifts of my great ancestors, philosophers famed the world over. It seems very clear to me that, if I had not come, from sheer force of affectionate propinquity you would have married Lady Maggie."

Nigel's frown deepened.

"Prince Shan!" he began.

Again the outstretched hand seemed as though the fingers were pressed against his mouth. He broke off abruptly in his protest.

"You would have lived a contented life, because that is your province," his companion continued. "You would have felt yourself happy because you would have been a faithful husband. But the time would have come when you would both have realised that you had missed the great things."

"This is idle prophecy," Nigel observed, a little impatiently. "I came to see you upon another matter."

"Humour me," the Prince begged. "I am going to speak to you even more intimately. I shall venture to do so because, after all, she is better known to me than to you. I am going to tell you that of all the women in the world, Naida Karetsky is the most likely to make you happy."

Nigel drew himself up a little stiffly.

"One does not discuss these things," he muttered.

"May I call that a touch of insularity?" Prince Shan pleaded, "because there is nothing else in the world so wonderful to discuss, in all respect and reverence, as the women who have made us feel. One last word, Lord Dorminster. The days of matrimonial alliances between the reigning families of Europe have come to an end under the influence of a different form of government, but there is a certain type of alliance, the utility of which remains unimpaired. I venture to say that you could not do your country a greater service, apart from any personal feelings you might have, than by marrying Mademoiselle Karetsky. There, you see, now I have finished. This is for your reflection, Lord Dorminster—just the measured statement of one who wears at least the cloak of philosophy by inheritance. Time passes. Your own reason for coming to see me has not yet been expounded."

"I have come to ask you to visit the Prime Minister before you leave England," Nigel announced.

Prince Shan changed his position slightly. His forehead was a little wrinkled. He was silent for a moment.

"If I pay more than a farewell visit of ceremony," he said, "that is to say, if I speak with Mr. Mervin Brown on things that count, I must anticipate a certain decision at which I have not yet wholly arrived."

Nigel had a sudden inspiration.

"You are seeking to bribe Maggie!" he exclaimed.

"That is not true," was the dignified reply.

"Then please explain," Nigel persisted.

Prince Shan rose to his feet. He walked to the heavy silk curtains which led into his own bedchamber, pushed them apart, and looked for a moment at the familiar objects in the room. Then he came back, glancing on his way at the ebony cabinet.

"One does not repeat one's mistakes," he said slowly, "and although you and I, Lord Dorminster, breathe the common air of the greater world, my instinct tells me that of certain things which have passed between your cousin and myself it is better that no mention ever be made. I wish to tell you this, however. There is in existence a document, my signature to which would, without a doubt, have a serious influence upon the destinies of this country. That document, unsigned, would be one of my marriage gifts to Lady Maggie—and as you know I have not yet had her answer. However, if you wish it, I will go to the Prime Minister."

Li Wen came silently in. He spoke to his master for a few minutes in Chinese. A faint smile parted the latter's lips.

"You can tell the person at the telephone that I will call within the next few minutes," he directed. "You will not object," he added, turning courteously to Nigel, "if I stop for a moment, on the way to Downing Street, at a small private hospital? An acquaintance of mine lies sick there and desires urgently to see me."

"I am entirely at your service," Nigel assured him.

Prince Shan, with many apologies, left Nigel alone in the car outside a tall, grey house in John Street, and, preceded by the white-capped nurse who had opened the door, climbed the stairs to the first floor of the celebrated nursing home, where, after a moment's delay, he was shown into a large and airy apartment. Immelan was in bed, looking very ill indeed. He was pale, and his china-blue eyes, curiously protruding, were filled with an expression of haunting fear. A puzzled doctor was standing by the bedside. A nurse, who was smoothing the bedclothes, glanced around at Prince Shan's entrance. The invalid started convulsively, and, clutching the pillows with his right hand, turned towards his visitor.

"So you've come!" he exclaimed. "Stay where yon are! Don't go! Doctor—nurse—leave us alone for a moment."

The nurse went at once. The doctor hesitated.

"My patient is a good deal exhausted," he said. "There are no dangerous symptoms at present, but—"

"I will promise not to distress him," Prince Shan interrupted. "I am myself somewhat pressed for time, and it is probable that your patient will insist upon speaking to me in private."

The doctor followed the nurse from the room. Prince Shan stood looking down upon the figure of quondam associate. There was a leaven of mild wonder in his clear eyes, a faintly contemptuous smile about the corners of his lips.

"So you are afraid of death, my friend," he observed, "afraid of the death you planned so skilfully for me."

"It is a lie!" Immelan declared excitedly. "Sen Lu was never killed by my orders. Listen! You have nothing against me. My death can do you no good. It is you who have been at fault. You—Prince Shan—the great diplomatist of the world—are gambling away your future and the future of a mighty empire for a woman's sake. You have treated me badly enough. Spare my life. Call in the doctor here and tell him what to do. He can find nothing in my system. He is helpless."

The smile upon the Prince's lips became vaguer, his expression more bland and indeterminate.

"My dear Immelan," he murmured, "you are without doubt delirious. Compose yourself, I beg."

A light that was almost tragic shone in the man's face. He sat up with a sudden access of strength.

"For the love of God, don't torture me!" he groaned. "The pains grow worse, hour by hour. If I die, the whole world shall know by whose hand."

The expression on Prince Shan's face remained unchanged. In his eyes, however, there was a little glint of something which seemed almost like foreknowledge,

"When you die," he pronounced calmly, "it will be by your own hand—not mine."

For some reason or other, Immelan accepted these measured words of prophecy as a total reprieve. The relief in his face was almost piteous. He seized his visitor's hand and would have fawned upon it. Prince Shan withdrew himself a little farther from the bed.

"Immelan," he said, "during my stay in England I have studied you and your methods, I have listened to all you have had to say and to propose, I have weighed the advantages and the disadvantages of the scheme you have outlined to me, and I only arrived at my decision after the most serious and unbiassed reflection. Your scheme itself was bold and almost splendid, but, as you yourself well know at the back of your mind, it would lay the seeds of a world tumult. I have studied history, Immelan, perhaps a little more deeply than you, and I do not believe in conquests. For the restoration to China of such lands as belong geographically and rightly to the Chinese Empire, I have my own plans. You, it seems to me, would make a cat's-paw of all Asia to gratify your hatred of England."

"A cat's-paw!" Immelan gasped. "Australia, New Zealand and India for Japan, new lands for her teeming population; Thibet for you, all Manchuria, and the control of the Siberian Railway!"

"These are dazzling propositions," Prince Shan admitted, "and yet—what about the other side of the Pacific?"

"America would be powerless," Immelan insisted.

"So you said before, in 1917," was the dry reminder. "I did not come here, however, to talk world politics with you. Those things for the moment are finished. I came in answer to your summons."

Immelan raised himself a little in the bed.

"You meant what you said?" he demanded, with hoarse anxiety. "There was no poison? Swear that?"

Prince Shan moved towards the door. His backward glance was coldly contemptuous.

"What I said, I meant," he replied. "Extract such comfort from it as you may."

He left the room, closing the door softly behind him. Immelan stared after him, hollow-eyed and anxious. Already the cold fears were seizing upon him once more.

Prince Shan rejoined Nigel, and the two men drove off to Downing Street. The former was silent for the first few minutes. Then he turned slightly towards his companion.

"The man Immelan is a coward," he declared. "It is he whom I have just visited."

Nigel shrugged his shoulders.

"So many men are brave enough in a fight," he remarked, "who lose their nerve on a sick bed."

"Bravery in battle," Prince Shan pronounced, "is the lowest form of courage. The blood is stirred by the excitement of slaughter as by alcohol. With Immelan I shall have no more dealings."

"Speaking politically as well as personally?" Nigel enquired.

The other smiled.

"I think I might go so far as to agree," he acquiesced, "but in a sense, there are conditions. You shall hear what they are. I will speak before you to the Prime Minister. See, up above is the sign of my departure."

Out of a little bank of white, fleecy clouds which hung down, here and there, from the blue sky, came the Black Dragon, her engines purring softly, her movements slow and graceful. Both men watched her for a moment in silence.

"At six o'clock to-morrow morning I start," Prince Shan announced. "My pilot tells me that the weather conditions are wonderful, all the way from here to Pekin. We shall be there on Wednesday."

"You travel alone?" Nigel enquired.

"I have passengers," was the quiet reply. "I am taking the English chaplain to your Church in Pekin."

The eyes of the two men met.

"It is an ingenious idea," Nigel admitted dryly.

"I wish to be prepared," his companion answered. "It may be that he is my only companion. In that case, I go back to a life lonelier than I have ever dreamed of. It is on the knees of the gods. So far there has come no word, but although I am not by nature an optimist, my superstitions are on my side. All the way over on my last voyage, when I lay in my berth, awake and we sailed over and through the clouds, my star, my own particular star, seemed leaning always down towards me, and for that reason I have faith."

Nigel glanced at his companion curiously but without speech. The car pulled up in Downing Street. The two men descended and found everything made easy for them. In two minutes they were in the presence of the Prime Minister.

Mr. Mervin Brown was at his best in the interview to which he

Comments (0)