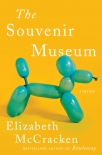

The Souvenir Museum, Elizabeth McCracken [bill gates best books .txt] 📗

- Author: Elizabeth McCracken

Book online «The Souvenir Museum, Elizabeth McCracken [bill gates best books .txt] 📗». Author Elizabeth McCracken

Thea had been a young mother and Florence an old one. They had brought their children to the same eurythmic dance class, Georgia because she was clumsy and Orly because he was graceful. The class was taught in a converted fire station by a Hawaiian woman the size of an eleven-year-old; she skipped and hit a round drum, followed by her dazzled students. There was a plate-glass window parents could spy through. “Make yourself a butterfly!” said the teacher. Georgia, age three, made herself a disgruntled Quasimodo with sciatica. Her leotard was too big and gapped around her legs, and Thea loved her entirely. “Which one’s yours?” Florence asked, and Thea pointed, said defensively, “I couldn’t skip to save my life,” and Florence said, “Chances are it won’t come to that.” Her own child, Orly, wore a little blue jumpsuit, like Jack LaLanne’s but mid–chubby thigh, and even when the class was led in “Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes,” Orly somehow did it expressively. He was an olive-skinned child with dark curly hair. Georgia was skinny and pale and freckled. Both of them three, but Thea was in her mid-twenties, and Florence somewhere in her forties. Old enough to be—

“Don’t say it,” said Florence, who in those days—on that day—wore striped dungarees and a sheer Indian shirt. Flowered, like the rumored muumuu. Altogether she seemed highly patterned, light blue eyes with navy blue flecks, a large nose with vertical creases at the bridge. Florence was happily married then to a lean professor of philosophy named Loren; Thea to Max, she thought also happily. If Thea tried—if she tried now, in Austin, Texas—she could conjure them up. The children, not the husbands; the husbands never met. Orly and Georgia, Georgia stumble skipping and Orly dancing. Beautiful children. That’s what Florence said that first day, as they watched the class: she turned to Thea and said, “Wouldn’t it be awful not to have beautiful children?”

The doll Thea sought was Baby Alive. You fed Baby Alive’s mechanical mouth, and Baby Alive’s mechanical digestive tract eventually emptied its mechanical bowels into its diaper, which you changed. Please, Georgia had said when she was eight, in the stunned weeping voice of a child whose parents didn’t understand her passion, peh-lease. “You’ve got a baby doll,” Thea had told her. “Pretend it can eat.” Just a year ago, at her wedding to Martine, Georgia had mentioned the doll, and Thea had said, “Oh, if you’d really bugged me I would have gotten it for you,” and Georgia had gasped, betrayed.

Thea couldn’t buy anything for the baby until after the birth, for fear of attracting the evil eye, but she could buy the doll for Georgia. Georgia would find it touching, or she’d be hurt. Thea wasn’t sure which reaction she hoped for. She knew her maternal love would always be edged with meanness, so as to matter: sometimes you needed a blade to get results.

Of Orly, Florence said, “Frankly, I worship that boy.” Thea thought it was a funny way to feel about your own child. You worried about your kid; you loved her; you wondered what her existence said about you. Florence’s adoration of Orly would have been intolerable had she not genuinely loved all children.

“I worship him,” said Florence, “and you worship Georgia. Geor-jah,” Florence called, and then said it again, the syllables distinct, cherry-dark and cherry-sweet.

“Hello,” said Georgia.

Florence said, as though just remembering, “I think there might be cake.”

They were sitting in Florence’s kitchen, the children cross-legged on the floor eating canned spaghetti, the mothers at the table eating pumpernickel bread and salted butter. The amiable Loren had baked the bread himself. At the mention of cake, Orly shut his eyes and rubbed his stomach. “Cake,” he said. “Cake, cake, cake, cake.” “Cake,” Georgia agreed, though she regarded Orly with caution: he kept saying it like a toy machine gun—“Cakecakecakecakecake.” She turned to her mother with a worried expression, a flutter of a smile, a private joke. No, thought Thea, I do not worship her. That would be immodest and unlucky. She worshipped no human being, except Florence herself, a little.

Every Saturday for two years, except summers, Thea and Georgia had lunch after dance with Florence and Orly in their house in Southeast Portland. The house had brown unpainted vertical siding, and looked like a hearty sport-related building somewhere in Europe: a sauna or ski chalet or the place where you strapped and unstrapped your ice skates at the edge of a frozen lake. It was the year that Thea’s husband was finishing his dissertation, followed by the year that their marriage was breaking up.

After lunch, in the piney backyard, Orly would cartwheel or walk on his hands or spin until he fell down, and Georgia would somersault knock-kneed and askew, and they both ended up on their backs, laughing at the sky.

Then kindergarten, and Georgia was off to Meriwether Lewis and Orly to Woodstock, where he lasted a week.

“He bit his teacher,” said Florence. “Mrs. Pietsch. I would have bit her, too.”

But once you get used to biting, to expulsion, it’s hard to stop. He’s a wonderful kid, his teachers said, but he bites. Or: He’s wonderful, but he can’t sit still. Or: He’s a good kid. Come get your kid. You need to get your kid. I’m sorry. Orly outgrew dance and he outgrew sports and he outgrew school. He outgrew his bed: he slept on his floor, in his closet, out in the world. In those years Thea heard from Florence only when he’d been missing awhile. “I was wondering if he’d called Georgia,” said Florence. “He’s always loved her so.” He always had loved her, Thea said; he never had called. He went to rehab twice the year he was thirteen. Twinkle-eyed Vandyked Loren turned out to have a nineteenth-century streak to his parenthood, and Orly was sent for three months to a camp in Idaho for wayward boys. He came home furious,

Comments (0)