Malaria and Rome: A History of Malaria in Ancient Italy, Robert Sallares [reading a book TXT] 📗

- Author: Robert Sallares

Book online «Malaria and Rome: A History of Malaria in Ancient Italy, Robert Sallares [reading a book TXT] 📗». Author Robert Sallares

¹⁵³ Martinez-Cortizas et al. (1999); Reale and Dirmeyer (2000).

¹⁵⁴ Potter (1979: 74) summarized the explosion in site numbers in south-eastern Etruria; Barker (1988); Sallares (1991: 29–34) on the spread of new crops.

104

Ecology of malaria

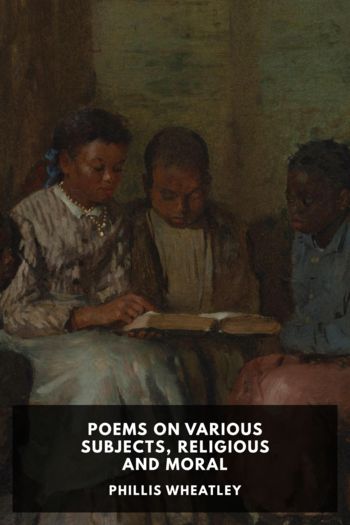

17. The Monti

Cimini, viewed from

the site of the Roman

villa at Lugnano in

Teverina. Most of

the redoubtable

ancient forest has

now disappeared.

Ecology of malaria

105

by more than a metre over the whole territory of Metapontum from the sixth to the fourth centuries . This was accompanied by extensive alluviation, which created marshy conditions suitable for Anopheles mosquitoes. The necropolis at Pantanello, whose very name indicates marshy conditions, outside Metapontum has yielded several skeletons which show signs of thalassaemia, an inherited genetic condition which confers a degree of resistance to P. falciparum malaria. This constitutes indirect evidence for the likely existence and activity of P. falciparum in southern Italy as well as Sicily during the classical Greek period.¹⁵⁵

This is not the place for an extensive discussion of deforestation in Italy in antiquity. Suffice it to say that there were massive forests in Italy, which grew during the mid-Holocene climatic optimum, following the end of the last Ice Age. Delano Smith has suggested that even the Tavoliere in Apulia, a semi-arid region today, might have been substantially covered by forest in the early Neolithic period.¹⁵⁶ In western central Italy, which is much better watered than the Tavoliere, the climax vegetation in the absence of human interference undoubtedly would be large forests in many areas.

Many of these forests were broken up during the first millennium by the demands of an increasing human population for open land for agriculture and by the ever-increasing demand of the Romans for timber. For example, Livy describes the Ciminian Forest. It was said to be so dense and forbidding c.310 that people were afraid even to approach it. Hardly anything is left of it today.¹⁵⁷ Pliny the Younger described the ancient woods of very tall trees on the Appennine mountains, above his estate at Tifernum in Umbria.¹⁵⁸ Theophrastus described very large forests in Latium at the end of the fourth century .¹⁵⁹ These forests were well watered ¹⁵⁵ Henneberg et al. (1992: 455) on thalassaemia. Their claim to have also found evidence for treponemal diseases such as syphilis in the skeletal remains from Metapontum remains controversial. Nevertheless malaria probably played a major role in the depopulation of the territory of Metapontum in the third century described by Carter (1990).

¹⁵⁶ Delano Smith (1978: 53), cf. Caldara and Pennetta (1996).

¹⁵⁷ Livy 9.36.1–8, discussed by Meiggs (1982: 246) and Cornell (1995: 355–6); Pratesi and Tassi (1977: 49) described the remnants of the Ciminian Forest.

¹⁵⁸ Pliny, Ep. 5.6.7: montes summa sui parte procera nemora et antiqua habent.

¹⁵⁹ Theophrastus, HP 5.8.3 and 2, ed. Amigues (1993): Ó d† t0n Lat≤nwn πfudroß p$sa: ka≥ Ó m†n pedein¶ d3fnhn πcei ka≥ murr≤nouß ka≥ øxu¶n qaumast&n: thlikaıta g¤r t¤ m&kh tvmnousin ¿ste e”nai dianek0ß t0n Turrhn≤dwn ËpÏ t¶n trÎpin: Ó d† ørein¶ pe»khn ka≥

ƒl3thn. tÏ d† Kirka∏on kalo»menon e”nai m†n £kran Ëyhl¶n, dase∏an d† sfÎdra ka≥ πcein drın ka≥ d3fnhn poll¶n ka≥ murr≤nouß . . . tÏn d† tÎpon e”nai ka≥ toıton nvan prÎsqesin ka≥

prÎteron m†n oˆn n[son e”nai tÏ Kirka∏on, nın d† ËpÏ potam0n tinwn proskec0sqai ka≥

106

Ecology of malaria

and had taller trees than the forests of southern Italy (although not as tall as those of Corsica). The lowland forests of bay, myrtle, and beech contained old trees tall enough to span the length of the keel of an Etruscan ship, while there were upland forests of fir and silver fir. The extant text seems confused, since beech ( Fagus silvatica, øx»h), which dominated the summits of the mountains of Lazio in the early modern period, belongs in the upland forests. If there were any beech forests in the lowlands of Latium c.300 , they were relics of previous colder periods, which were doomed to extinction during the warmer climate of the Roman Empire.¹⁶⁰

Theophrastus’ description of the region around ancient Circeii shows that he was aware of ongoing environmental change in the form of the alluviation which was thought to have attached Circeii, regarded in antiquity as once having been an island, to the mainland of Italy. Monte Circeo is regarded by modern geologists as e”nai ]∫Îna. t[ß d† n&sou tÏ mvgeqoß per≥ øgdo&konta stad≤ouß . . . t0n g¤r ƒn t∫ Lat≤n7

kal0n ginomvnwn Ëperbol∫ ka≥ t0n ƒlat≤nwn ka≥ t0n peuk≤nwn—me≤zw g¤r taıta ka≥

kall≤w t0n ∞Italik0n. (The whole territory of the Latins is well-watered; the plains contain forests of bay, myrtle, and wonderful beech. They fell timbers of it so long that they span the entire length of the keel of an Etruscan ship. The hills have forests of fir and silver-fir . . . The so-called Circaion is an elevated promontory, but it is densely wooded and has oak trees, a lot of bay, and myrtle. The land surrounding the Circaion has been created recently by sedimentation from certain rivers, but the Circaion was formerly an island. The island was about eighty stades in circumference . . . silver-fir and fir grow extremely tall in Latium and are taller and finer than in southern Italy.).

¹⁶⁰ Quilici (1979: 76–87) on the ancient forests of the Campagna Romana, cf. Pratesi and Tassi (1977: 76); Traina (1990: 16); Grandazzi (1997: 65–73) on the environment of Latium.

Meiggs (1982: 219, 243–5) and Fraser (1994: 184–6) discussed Theophrastus on the forests of Latium without considering the problem of the beeches. The inaccuracy of Theophrastus’

information (if it is not simply the case that the text has become garbled during manuscript transmission) fits Fraser’s emphasis on the paucity of information available to Theophrastus from the western Mediterranean in contrast to the large volume of data yielded by

Comments (0)