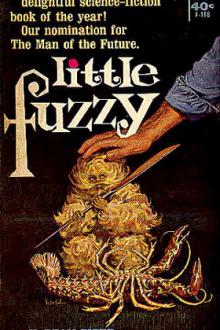

Little Fuzzy, H. Beam Piper [ebook reader computer txt] 📗

- Author: H. Beam Piper

Book online «Little Fuzzy, H. Beam Piper [ebook reader computer txt] 📗». Author H. Beam Piper

“Well, we have the Holloway Fuzzies placed on Xerxes,” the Chief Justice said. “We can hear the testimony of the people who worked with them there at any time. Now, I want to hear from Dr. Ernst Mallin.”

Coombes was on his feet again. “Your Honors, before any further testimony is heard, I would like to confer with my client privately.”

“I fail to see any reason why we should interrupt proceedings for that purpose, Mr. Coombes. You can confer as much as you wish with your client after this session, and I can assure you that you will be called upon to do nothing on his behalf until then.” He gave a light tap with his gavel and then said: “Dr. Ernst Mallin will please take the stand.”

XVErnst Mallin shrank, as though trying to pull himself into himself, when he heard his name. He didn’t want to testify. He had been dreading this moment for days. Now he would have to sit in that chair, and they would ask him questions, and he couldn’t answer them truthfully and the globe over his head—

When the deputy marshal touched his shoulder and spoke to him, he didn’t think, at first, that his legs would support him. It seemed miles, with all the staring faces on either side of him. Somehow, he reached the chair and sat down, and they fitted the helmet over his head and attached the electrodes. They used to make a witness take some kind of an oath to tell the truth. They didn’t any more. They didn’t need to.

As soon as the veridicator was on, he looked up at the big screen behind the three judges; the globe above his head was a glaring red. There was a titter of laughter. Nobody in the Courtroom knew better than he what was happening. He had screens in his laboratory that broke it all down into individual patterns—the steady pulsing waves from the cortex, the alpha and beta waves; beta-aleph and beta-beth and beta-gimel and beta-daleth. The thalamic waves. He thought of all of them, and of the electromagnetic events which accompanied brain activity. As he did, the red faded and the globe became blue. He was no longer suppressing statements and substituting other statements he knew to be false. If he could keep it that way. But, sooner or later, he knew, he wouldn’t be able to.

The globe stayed blue while he named himself and stated his professional background. There was a brief flicker of red while he was listing his publication—that paper, entirely the work of one of his students, which he had published under his own name. He had forgotten about that, but his conscience hadn’t.

“Dr. Mallin,” the oldest of the three judges, who sat in the middle, began, “what, in your professional opinion, is the difference between sapient and nonsapient mentation?”

“The ability to think consciously,” he stated. The globe stayed blue.

“Do you mean that nonsapient animals aren’t conscious, or do you mean they don’t think?”

“Well, neither. Any life form with a central nervous system has some consciousness—awareness of existence and of its surroundings. And anything having a brain thinks, to use the term at its loosest. What I meant was that only the sapient mind thinks and knows that it is thinking.”

He was perfectly safe so far. He talked about sensory stimuli and responses, and about conditioned reflexes. He went back to the first century Pre-Atomic, and Pavlov and Korzybski and Freud. The globe never flickered.

“The nonsapient animal is conscious only of what is immediately present to the senses and responds automatically. It will perceive something and make a single statement about it—this is good to eat, this sensation is unpleasant, this is a sex-gratification object, this is dangerous. The sapient mind, on the other hand, is conscious of thinking about these sense stimuli, and makes descriptive statements about them, and then makes statements about those statements, in a connected chain. I have a structural differential at my seat; if somebody will bring it to me—”

“Well, never mind now, Dr. Mallin. When you’re off the stand and the discussion begins you can show what you mean. We just want your opinion in general terms, now.”

“Well, the sapient mind can generalize. To the nonsapient animal, every experience is either totally novel or identical with some remembered experience. A rabbit will flee from one dog because to the rabbit mind it is identical with another dog that has chased it. A bird will be attracted to an apple, and each apple will be a unique red thing to peck at. The sapient being will say, ‘These red objects are apples; as a class, they are edible and flavorsome.’ He sets up a class under the general label of apples. This, in turn, leads to the formation of abstract ideas—redness, flavor, et cetera—conceived of apart from any specific physical object, and to the ordering of abstractions—‘fruit’ as distinguished from apples, ‘food’ as distinguished from fruit.”

The globe was still placidly blue. The three judges waited, and he continued:

“Having formed these abstract ideas, it becomes necessary to symbolize them, in order to deal with them apart from the actual object. The sapient being is a symbolizer, and a symbol communicator; he is able to convey to other sapient beings his ideas in symbolic form.”

“Like ‘Pa-pee Jaak’?” the judge on his right, with the black mustache, asked.

The globe flashed red at once.

“Your Honors, I cannot consider words picked up at random and learned by rote speech. The Fuzzies have merely learned to associate that sound with a specific human, and use it as a signal, not as a symbol.”

The globe was still red. The Chief Justice, in the middle, rapped with his gavel.

“Dr. Mallin! Of all the people on this planet, you at least should know the impossibility

Comments (0)