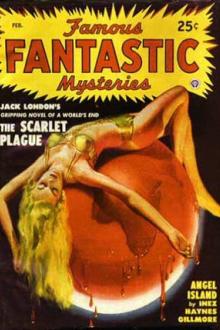

Angel Island, Inez Haynes Gillmore [the two towers ebook txt] 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island, Inez Haynes Gillmore [the two towers ebook txt] 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

color and energy. Frank also had a different look. His eyes had kindled,

his face had become noticeably more alive. But it was the fire of the

intellect that had produced this frigid glow.

“Seen anything?” Frank Merrill inquired.

“Not a thing.”

“You don’t think they’re frightened enough not to come back?”

The gleam in Ralph Addington’s eye changed to flame. “I don’t think

they’re frightened at all. They’ll come back all right. There’s only one

thing that you can depend on in women; and that is that you can’t lose

them.”

“I can scarcely wait to see them again,” Frank exclaimed eagerly.

“Addington, I can write a monograph on those flying-maidens that will

make the whole world gasp. This is the greatest discovery of modern

times. Man alive, don’t you itch to get to paper and pencil?”

“Not so I’ve noticed it,” Ralph replied with contemptuous emphasis. “I

shall lie awake nights, just the same though.”

“Say, fellers, we didn’t dream that, did we?” Billy Fairfax called

suddenly, rolling out of the sleep that had followed their all-night

talk.

“Well, I reckon if it wasn’t for the other four, no one of us would

trust his own senses,” Frank Merrill said dryly.

“If you’d listened to me in the beginning,” Honey Smith remarked in a

drowsy voice, not bothering to open his, eyes, “I wouldn’t be the

I-told-you-so kid now.”

“Well, if you’d listened to me and Pete!” said Billy Fairfax; “didn’t we

think, way back there that first day, that our lamps were on the blink

because we saw black spots? Great Scott, what dreams I’ve had,” he went

on, “a mixture of ‘Arabian Nights,’ ‘Gulliver’s Travels,’ ‘Peter

Wilkins,’ ‘Peter Pan,’ ‘Goosie,’ Jules, Verne, H. G. Wells, and every

dime novel I’ve ever read. Do you suppose they’ll come back?”

“I’ve just talked that over with Ralph,” Frank Merrill answered him. “If

we’ve frightened them away forever, it will be a terrible loss to

science.”

Ralph Addington emitted one of his cackling, ironic laughs. “I guess I’m

not worrying as much about science as I might. But as to their coming

back - why, it stands to reason that they’ll have just as much curiosity

about us as we have about them. Curiosity’s a woman’s strong point, you

know. Oh, they’ll come back all right! The only question is, How soon?”

“It made me dream of music - of Siegfried.” It was Pete Murphy who spoke

and he seemed to plump from sleep straight into the conversation. “What

a theme for grand opera. Women with wings! Flying-girls! Will you tell

me what the Hippodrome! has on Angel Island?”

“Nothing,” said Honey Smith, “except this - you can get acquainted with

a Hippodrome girl - how long is it going to take us to get acquainted

with these angels?”

“Not any longer than usual,” said Ralph Addington with an expressive

wink. “Leave that to me. I’m going now to see what I can see.” He walked

rapidly down the beach, scaled the southern reef, and stood there

studying the horizon.

The others remained sitting on the sand. For a while they watched Ralph.

Then they talked the whole thing over with as much interest as if they

had not yet discussed it. Ralph rejoined them and they went through it

again. It was as though by some miracle of mind-transference, they had

all dreamed the same dream; as though, by some miracle of

sight-transference they had all seen the same vision; as though, by some

miracle of space-transference, they had all stepped into the fourth

dimension. Their comment was ever of the wonder of their strange

adventure, the beauty, the thrill, the romance of it. It had brought out

in them every instinct of chivalry and kindness, it had developed in

them every tendency towards high-mindedness and idealism. Angel Island

would be an Atlantis, an Eden, an Arden, an Arcadia, a Utopia, a

Milleamours, a Paradise, the Garden of Hesperides. Into it the Golden

Age would come again. They drew glowing pictures of the wonderful

friendships that would grow up on Angel Island between them and their

beautiful visitors. These poetic considerations gave way finally to a

discussion of ways and means. They agreed that they must get to work at

once on some sort of shelter for their guests, in case the weather

should turn bad. They even discussed at length the best methods of

teaching the English language. They talked the whole morning, going over

the same things again and again, questioning each other eagerly without

listening for an answer, interrupting ruthlessly, and then adding

nothing.

The day passed without event. At the slightest sound they all jumped.

Their sleeplessness was beginning to tell on them and their nerves were

still obsessed by the unnaturalness of their experience. It was a long

time before they quieted down, but the night passed without

interruption. So did the next day. Another day went by and another, and

during this time they did little but sit about and talk.

“See here, boys,” Ralph Addington said one morning. “I say we get

together and build some cabins. There’s no calculating how long this

grand weather’ll keep up. The first thing we know we’ll be up against a

rainy season. Isn’t that right, Professor?”

On most practical matters Ralph treated Frank Merrill’s opinion with a

contempt that was offensively obvious to the others. In questions of

theory or of abstruse information, he was foolishly deferential. At

those times, he always gave Frank his title of Professor.

“I hardly think so,” Frank Merrill answered. “I think we’ll have an

equable, semi-tropical climate all the year round - about like

Honolulu.”

“Well, anyway,” Ralph Addington went on, “it’s barbarous living like

this. And we want to be prepared for anything.” His gaze left Frank

Merrill’s face and traveled with a growing significance to each of the

other three. “Anything,” he repeated with emphasis. “We’ve got enough

truck here to make a young Buckingham Palace. And we’ll go mad sitting

round waiting for those air-queens to pay us a visit. How about it?”

“It’s an excellent idea,” Frank Merrill said heartily. “I have been on

the point of proposing it many times myself.”

However, they seemed unable to pull themselves together; they did

nothing that day. But the next morning, urged back to work by the

harrying monotony of waiting, they began to clear a space among the

trees close to the beach. Two of them had a little practical building

knowledge: Ralph Addington who had roughed it in many strange countries;

Billy Fairfax who, in the San Francisco earthquake, had on a wager built

himself a house. They worked with all their initial energy. They worked

with the impetus that comes from capable supervision. And they worked as

if under the impulse of some unformulated motive. As usual, Honey Smith

bubbled with spirits. Billy Fairfax and Pete Murphy hardly spoke, so

close was their concentration. Ralph Addington worked longer and harder

than anybody, and even Honey was not more gay; he whistled and sang

constantly. Frank Merrill showed no real interest in these proceedings.

He did his fair share of the work, but obviously without a driving

motive. He had reverted utterly to type. He spent his leisure writing a

monograph. When inspiration ran low, he occupied himself doctoring

books. Eternally, he hunted for the flat stones between which he pressed

their swollen bulks back to shape. Eternally he puttered about, mending

and patching them. He used to sit for hours at a desk which he had

rescued from the ship’s furniture. The others never became accustomed to

the comic incongruity of this picture - especially when, later, he

virtually boxed himself in with a trio of bookcases.

“Wouldn’t you think he was sitting in an office?” Ralph Addington said.

“Curious about Merrill,” Honey Smith answered, indulging in one of his

sudden, off-hand characterizations, bull’s-eye shots every one of them.

“He’s a good man, ruined by culturine. He’s the bucko-mate type

translated into the language of the academic world. Three centuries ago

he’d have been a Drake or a Frobisher. And to-day, even, if he’d

followed the lead of his real ability, he’d have made a great financier,

a captain of industry or a party boss. But, you see, he was brought up

to think that book-education was the whole cheese. The only ambition he

knows is to make good in the university world. How I hated that college

atmosphere and its insistence on culture! That was what riled me most

about it. As a general thing, I detest a professor. Can’t help liking

old Frank, though.”

The four men virtually took no time off from work; or at least the

change of work that stood for leisure was all in the line of

home-making. Eternally, they joked each other about these womanish

occupations; but they all kept steadily to it. Ralph Addington and Honey

Smith put the furniture into shape, repairing and polishing it. Billy

Fairfax sorted out the glass, china, tools, household utensils of every

kind.

Pete Murphy went through the trunks with his art side uppermost. He

collected all kinds of Oriental bric-a-brac, pictures and draperies. He

actually mended and pressed things; he had all the artist’s capability

in these various feminine lines. When the others joked him about his

exotic and impracticable tastes, he said that, before he left, he

intended to establish a museum of fine arts, on Angel Island.

Hard as the men worked, they had always the appearance of those who

await the expected. But the expected did not occur; and gradually the

sharp edge of anticipation wore dull. Emotionally they calmed. Their

nerves settled to a normal condition. The sudden whirr of a bird’s

flight attracted only a casual glance. In Ralph Addington alone,

expectation maintained itself at the boiling point. He trained himself

to work with one eye searching the horizon. One afternoon, when they had

scattered for a siesta, his hoarse cry brought them running to the beach

from all directions.

So suddenly had the girls appeared that they might have materialized

from the air. This time they had not come from the sea. When Ralph

discovered them, they were hovering back of them above the trees that

banded the beach. The sun was setting, blood-red; the whole western sky

had broken away. The girls seemed to be floating in a sea of

crimson-amber ether. Its light brought lustre to every feather; it

turned the edges of their wings to flame; it changed their smoothly

piled hair to helmets of burnished metal.

The men tore from the beach to the trees at full speed. For a moment the

violence of this action threw the girls into a panic. They fluttered,

broke lines, flew high, circled. And all the time, they uttered shrill

cries of distress.

“They’re frightened,” Billy Fairfax said. “Keep quiet, boys.”

The men stopped running, stood stock-still.

Gradually the girls calmed, sank, took up the interweaving figures of

their air-dance. If at their first appearance they seemed creatures of

the sea, this time they were as distinctively of the forest. They looked

like spirits of the trees over which they hovered. Indeed, but for their

wings they might have been dryads. Wreaths of green encircled their

heads and waists. Long leafy streamers trailed from their shoulders.

Often in the course of their aerial play, they plunged down into the

feathery tree-tops.

Once, the blonde with the blue wings sailed out of the group and

balanced herself for a toppling second on a long, outstretching bough.

“Good Lord, what a picture!” Pete Murphy said.

As if she understood, she repeated her performance. She cast a glance

over her shoulder at them -

Comments (0)