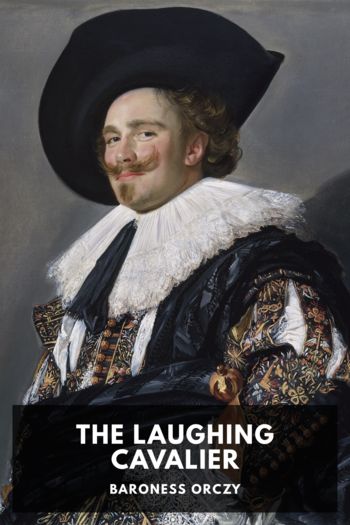

The Laughing Cavalier, Baroness Orczy [the beginning after the end read novel TXT] 📗

- Author: Baroness Orczy

Book online «The Laughing Cavalier, Baroness Orczy [the beginning after the end read novel TXT] 📗». Author Baroness Orczy

“Will you deign to allow me, mejuffrouw,” he said, “at any rate to tell you one certain, unvarnished truth, which mayhap you will not even care to believe, and that is that I would give my life—the few chances, that is, that I still have of it—to obliterate from your mind the memory of the past few days.”

“That you cannot do, sir,” she rejoined, “but you would greatly ease the load of sorrow which you have helped to lay upon me, if you gave me the assurance which I ask.”

The prisoner did not reply immediately, and for one brief moment there was absolute silence in this tiny room, a silence so tense and so vivid that an eternity of joy and sorrow, of hope and of fear seemed to pass over the life of these three human creatures here. All three had eyes and ears only for one another: the world with its grave events, its intrigues and its wars fell quite away from them: they were the only people existing—each for the other—for this one brief instant that passed by.

The fire crackled in the huge hearth, and slowly the burning wood ashes fell with a soft swishing sound one by one. But outside all was still: not a sound of the busy life around the molens, of conspiracies and call to arms, penetrated the dense veil of fog which lay upon the low-lying land.

At last the prisoner spoke.

“ ’Tis easily done, mejuffrouw,” he said, and all at once his whole face lit up with that lighthearted gaiety, that keen sense of humour which would no doubt follow him to the grave, “that assurance I can easily give you. I was the sole criminal in the hideous outrage which brought so much sorrow upon you. Had I the least hope that God would hear the prayer of so despicable a villain as I am I would beg of Him to grant you oblivion of my deed. As for me,” he added and now real laughter was dancing in his eyes: they mocked and challenged and called back the joy of life, “as for me, I am impenitent. I would not forget one minute of the last four days.”

“Tomorrow then you can take the remembrance with you to the gallows,” said Stoutenburg sullenly.

Though a sense of intense relief pervaded him now, since by his assertions Diogenes had completely vindicated him as well as Nicolaes in Gilda’s sight, his dark face showed no signs of brightening. That fierce jealousy of this nameless adventurer which had assailed him awhile ago was gnawing at his heart more insistently than before; he could not combat it, even though reason itself argued that jealousy of so mean a knave was unworthy, and that Gilda’s compassion was only the same that she would have extended to any dog that had been hurt.

Even now—reason still argued—was it not natural that she should plead for the villain just as any tender-natured woman would plead even for a thief. Women hate the thought of violent death, only an amazon would desire to mete out death to any enemy: Gilda was warmhearted, impulsive, the ugly word “gallows” grated no doubt unpleasantly on her ear. But even so, and despite the dictates of reason, Stoutenburg’s jealousy and hatred were up in arms the moment she turned pleading eyes upon him.

“My lord,” she said gently, “I pray you to remember that by this open confession this … this gentleman has caused me infinite happiness. I cannot tell you what misery my own suspicions have caused me these past two days. They were harder to bear than any humiliation or sorrow which I had to endure.”

“This varlet’s lies confirmed you in your suspicions, Gilda,” retorted Stoutenburg roughly, “and his confession—practically at the foot of the gallows—is but a tardy one.”

“Do not speak so cruelly, my lord,” she pleaded, “you say that … that you have some regard for me … let not therefore my prayer fall unheeded on your ear …”

“Your prayer, Gilda?”

“My prayer that you deal nobly with an enemy, whose wrongs to me I am ready to forgive. …”

“By St. Bavon, mejuffrouw,” here interposed the prisoner firmly, “an mine ears do not deceive me you are even now pleading for my life with the Lord of Stoutenburg.”

“Indeed, sir, I do plead for it with my whole heart,” she said earnestly.

“Ye gods!” he exclaimed, “an ye do not interfere!”

“My lord!” urged Gilda gently, “for my sake. …”

Her words, her look, the tears that despite her will had struggled to her eyes, scattered to the winds Stoutenburg’s reasoning powers. He felt now that nothing while this man lived would ever still that newly-risen passion of jealousy. He longed for and desired this man’s death more even than that of the Prince of Orange. His honour had been luckily whitewashed before Gilda by this very man whom he hated. He had a feeling that within the last half-hour he had made enormous strides in her regard. Already he persuaded himself that she was looking on him more kindly, as if remorse at her unjust suspicions of him had touched her soul on his behalf.

Everything now would depend on how best he could seem noble and generous in her sight; but he was more determined than ever that his enemy should stand disgraced before her first and die on the gallows on the morrow.

Then it was that putting up his hand to the region of his heart, which indeed was beating furiously, it encountered the roll of parchment which lay in the inner pocket of his doublet. Fate, chance, his own foresight, were indeed making the way easy for him, and quicker than lightning his tortuous brain had already formed a plan upon which he promptly acted now.

“Gilda,” he said quietly, “though God knows how ready I am to do you service in all things, this is a case where weakness on my part would be almost

Comments (0)