An Introduction to Philosophy, George Stuart Fullerton [books to read in your 20s .TXT] 📗

- Author: George Stuart Fullerton

- Performer: -

Book online «An Introduction to Philosophy, George Stuart Fullerton [books to read in your 20s .TXT] 📗». Author George Stuart Fullerton

As for Aristotle (384-322, B.C.), who also distinguished between the lower psychical functions and the higher, we find him sometimes speaking of soul and body in such a way as to lead men to ask themselves whether he is really speaking of two things at all; but when he specifically treats of the nous or reason, he insists upon its complete detachment from everything material. Man's reason is not subjected to the fate of the lower psychical functions, which, as the "form" of the body, perish with the body; it enters from without, and it endures after the body has passed away. It is interesting to note, however, an occasional lapse even in Aristotle. When he comes to speak of the relation to the world of the Divine Mind, the First Cause of Motion, which he conceives as pure Reason, he represents it as touching the world, although it remains itself untouched. We seem to find here just a flavor—an inconsistent one—of the material.

Such reflections as those of Plato and Aristotle bore fruit in later ages. When we come down to Plotinus the Neo-Platonist (204-269, A.D.), we have left the conception of the soul as a warm breath, or as composed of fine round atoms, far behind. It has become curiously abstract and incomprehensible. It is described as an immaterial substance This substance is, in a sense, in the body, or, at least, it is present to the body. But it is not in the body as material things are in this place or in that. It is as a whole in the whole body, and it is as a whole in every part of the body. Thus the soul may be regarded as divisible, since it is distributed throughout the body; but it must also be regarded as indivisible, since it is wholly in every part.

Let the man to whom such sentences as these mean anything rejoice in the meaning that he is able to read into them! If he can go as far as Plotinus, perhaps he can go as far as Cassiodorus (477-570, A.D.), and maintain that the soul is not merely as a whole in every part of the body, but is wholly in each of its own parts.

Upon reading such statements one's first impulse is to exclaim: How is it possible that men of sense should be led to speak in this irresponsible way? and when they do speak thus, is it conceivable that other men should seriously occupy themselves with what they say?

But if one has the historic sense, and knows something of the setting in which such doctrines come to the birth, one cannot regard it as remarkable that men of sense should urge them. No one coins them independently out of his own brain; little by little men are impelled along the path that leads to such conclusions. Plotinus was a careful student of the philosophers that preceded him. He saw that mind must be distinguished from matter, and he saw that what is given a location in space, in the usual sense of the words, is treated like a material thing. On the other hand, he had the common experience that we all have of a relation between mind and body. How do justice to this relation, and yet not materialize mind?

What he tried to do is clear, and it seems equally clear that he had good reason for trying to do it. But it appears to us now that what he actually did was to make of the mind or soul a something very like an inconsistent bit of matter, that is somehow in space, and yet not exactly in space, a something that can be in two places at once, a logical monstrosity. That his doctrine did not meet with instant rejection was due to the fact, already alluded to, that our experience of the mind is something rather dim and elusive. It is not easy for a man to say what it is, and, hence, it is not easy for a man to say what it is not.

The doctrine of Plotinus passed over to Saint Augustine, and from him it passed to the philosophers of the Middle Ages. How extremely difficult it has been for the world to get away from it at all, is made clearly evident in the writings of that remarkable man Descartes.

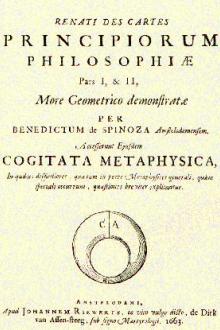

Descartes wrote in the seventeenth century. The long sleep of the Middle Ages was past, and the several sciences had sprung into a vigorous and independent life. It was not enough for Descartes to describe the relation of mind and body in the loose terms that had prevailed up to his time. He had made a careful study of anatomy, and he realized that the brain is a central organ to which messages are carried by the nerves from all parts of the body. He knew that an injury to the nerve might prevent the receipt of a message, i.e. he knew that a conscious sensation did not come into being until something happened in the brain.

Nor was he content merely to refer the mind to the brain in a general way. He found the "little pineal gland" in the midst of the brain to be in what he regarded as an admirable position to serve as the seat of the soul. To this convenient little central office he relegated it; and he describes in a way that may to-day well provoke a smile the movements that the soul imparts to the pineal gland, making it incline itself in this direction and in that, and making it push the "animal spirits," the fluid contained in the cavities of the brain, towards various "pores."

Thus he writes:[1] "Let us, then, conceive of the soul as having her chief seat in the little gland that is in the middle of the brain, whence she radiates to all the rest of the body by means of the spirits, the nerves, and even the blood, which, participating in the impressions of the spirits, can carry them through the arteries to all the members." And again: "Thus, when the soul wills to call anything to remembrance, this volition brings it about that the gland, inclining itself successively in different directions, pushes the spirits towards divers parts of the brain, until they find the part which has the traces that the object which one wishes to recollect has left there."

We must admit that Descartes' scientific studies led him to make this mind that sits in the little pineal gland something very material. It is spoken of as though it pushed the gland about; it is affected by the motions of the gland, as though it were a bit of matter. It seems to be a less inconsistent thing than the "all in the whole body" soul of Plotinus; but it appears to have purchased its comprehensibility at the expense of its immateriality.

Shall we say that Descartes frankly repudiated the doctrine that had obtained for so many centuries? We cannot say that; he still held to it. But how could he? The reader has perhaps remarked above that he speaks of the soul as having her chief seat in the pineal gland. It seems odd that he should do so, but he still held, even after he had come to his definite conclusions as to the soul's seat, to the ancient doctrine that the soul is united to all the parts of the body "conjointly." He could not wholly repudiate a venerable tradition.

We have seen, thus, that men first conceived of the mind as material and later came to rebel against such a conception. But we have seen, also, that the attempt to conceive it as immaterial was not wholly successful. It resulted in a something that we may describe as inconsistently material rather than as not material at all.

32. MODERN COMMON SENSE NOTIONS OF THE MIND.—Under this heading I mean to sum up the opinions as to the nature of the mind usually held by the intelligent persons about us to-day who make no claim to be regarded as philosophers. Is it not true that a great many of them believe:—

(1) That the mind is in the body?

(2) That it acts and reacts with matter?

(3) That it is a substance with attributes?

(4) That it is nonextended and immaterial?

I must remark at the outset that this collection of opinions is by no means something gathered by the plain man from his own experience. These opinions are the echoes of old philosophies. They are a heritage from the past, and have become the common property of all intelligent persons who are even moderately well-educated. Their sources have been indicated in the preceding sections; but most persons who cherish them have no idea of their origin.

Men are apt to suppose that these opinions seem reasonable to them merely for the reason that they find in their own experience evidence of their truth. But this is not so.

Have we not seen above how long it took men to discover that they must not think of the mind as being a breath, or a flame, or a collection of material atoms? The men who erred in this way were abler than most of us can pretend to be, and they gave much thought to the matter. And when at last it came to be realized that mind must not thus be conceived as material, those who endeavored to conceive it as something else gave, after their best efforts, a very queer account of it indeed.

Is it in the face of such facts reasonable to suppose that our friends and acquaintances, who strike us as having reflective powers in nowise remarkable, have independently arrived at the conception that the mind is a nonextended and immaterial substance? Surely they have not thought all this out for themselves. They have taken up and appropriated unconsciously notions which were in the air, so to speak. They have inherited their doctrines, not created them. It is well to remember this, for it may make us the more willing to take up and examine impartially what we have uncritically turned into articles of belief.

The first two articles, namely, that the mind is in the body and that it acts upon, and is acted upon by, material things, I shall discuss at length in the next chapter. Here I pause only to point out that the plain man does not put the mind into the body quite unequivocally. I think it would surprise him to be told that a line might be drawn through two heads in such a way as to transfix two minds. And I remark, further, that he has no clear idea of what it means for mind to act upon body or body to act upon mind. How does an immaterial thing set a material thing in motion? Can it touch it? Can it push it? Then what does it do?

But let us pass on to the last two articles of faith mentioned above.

We all draw the distinction between substance and its attributes or qualities. The distinction was remarked and discussed many centuries ago, and much has been written upon it. I take up the ruler on my desk; it is recognized at once as a bit of wood. How? It has such and such qualities. My paper-knife is of silver. How do I know it? It has certain other qualities. I speak of my mind. How do I know that I have a mind? I have sensations and ideas. If I experienced no mental phenomena of any sort, evidence of the existence of a mind would be lacking.

Now, whether I am concerned with the ruler, with the paper-knife, or with the mind, have I direct evidence of the existence of anything more than the whole group of qualities? Do I ever perceive the substance?

In the older philosophy, the substance (substantia) was conceived to be a something not directly perceived, but only inferred to exist—a something underlying the

Comments (0)