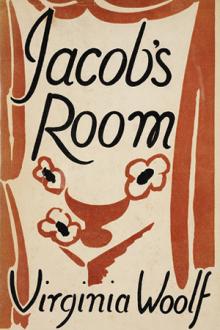

Jacob's Room, Virginia Woolf [non fiction books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Virginia Woolf

- Performer: 0140185704

Book online «Jacob's Room, Virginia Woolf [non fiction books to read .txt] 📗». Author Virginia Woolf

passed him his cup there was that quiver in her flanks. Bowley saw what

was up-asked Jimmy to breakfast. Helen must have confided in Rose. For

my own part, I find it exceedingly difficult to interpret songs without

words. And now Jimmy feeds crows in Flanders and Helen visits hospitals.

Oh, life is damnable, life is wicked, as Rose Shaw said.

The lamps of London uphold the dark as upon the points of burning

bayonets. The yellow canopy sinks and swells over the great four-poster.

Passengers in the mail-coaches running into London in the eighteenth

century looked through leafless branches and saw it flaring beneath

them. The light burns behind yellow blinds and pink blinds, and above

fanlights, and down in basement windows. The street market in Soho is

fierce with light. Raw meat, china mugs, and silk stockings blaze in it.

Raw voices wrap themselves round the flaring gas-jets. Arms akimbo, they

stand on the pavement bawling—Messrs. Kettle and Wilkinson; their wives

sit in the shop, furs wrapped round their necks, arms folded, eyes

contemptuous. Such faces as one sees. The little man fingering the meat

must have squatted before the fire in innumerable lodging-houses, and

heard and seen and known so much that it seems to utter itself even

volubly from dark eyes, loose lips, as he fingers the meat silently, his

face sad as a poet’s, and never a song sung. Shawled women carry babies

with purple eyelids; boys stand at street corners; girls look across the

road—rude illustrations, pictures in a book whose pages we turn over

and over as if we should at last find what we look for. Every face,

every shop, bedroom window, public-house, and dark square is a picture

feverishly turned—in search of what? It is the same with books. What do

we seek through millions of pages? Still hopefully turning the pages—

oh, here is Jacob’s room.

He sat at the table reading the Globe. The pinkish sheet was spread flat

before him. He propped his face in his hand, so that the skin of his

cheek was wrinkled in deep folds. Terribly severe he looked, set, and

defiant. (What people go through in half an hour! But nothing could save

him. These events are features of our landscape. A foreigner coming to

London could scarcely miss seeing St. Paul’s.) He judged life. These

pinkish and greenish newspapers are thin sheets of gelatine pressed

nightly over the brain and heart of the world. They take the impression

of the whole. Jacob cast his eye over it. A strike, a murder, football,

bodies found; vociferation from all parts of England simultaneously. How

miserable it is that the Globe newspaper offers nothing better to Jacob

Flanders! When a child begins to read history one marvels, sorrowfully,

to hear him spell out in his new voice the ancient words.

The Prime Minister’s speech was reported in something over five columns.

Feeling in his pocket, Jacob took out a pipe and proceeded to fill it.

Five minutes, ten minutes, fifteen minutes passed. Jacob took the paper

over to the fire. The Prime Minister proposed a measure for giving Home

Rule to Ireland. Jacob knocked out his pipe. He was certainly thinking

about Home Rule in Ireland—a very difficult matter. A very cold night.

The snow, which had been falling all night, lay at three o’clock in the

afternoon over the fields and the hill. Clumps of withered grass stood

out upon the hill-top; the furze bushes were black, and now and then a

black shiver crossed the snow as the wind drove flurries of frozen

particles before it. The sound was that of a broom sweeping—sweeping.

The stream crept along by the road unseen by any one. Sticks and leaves

caught in the frozen grass. The sky was sullen grey and the trees of

black iron. Uncompromising was the severity of the country. At four

o’clock the snow was again falling. The day had gone out.

A window tinged yellow about two feet across alone combated the white

fields and the black trees …. At six o’clock a man’s figure carrying a

lantern crossed the field …. A raft of twig stayed upon a stone,

suddenly detached itself, and floated towards the culvert …. A load of

snow slipped and fell from a fir branch …. Later there was a mournful

cry …. A motor car came along the road shoving the dark before it ….

The dark shut down behind it….

Spaces of complete immobility separated each of these movements. The

land seemed to lie dead …. Then the old shepherd returned stiffly

across the field. Stiffly and painfully the frozen earth was trodden

under and gave beneath pressure like a treadmill. The worn voices of

clocks repeated the fact of the hour all night long.

Jacob, too, heard them, and raked out the fire. He rose. He stretched

himself. He went to bed.

The Countess of Rocksbier sat at the head of the table alone with Jacob.

Fed upon champagne and spices for at least two centuries (four, if you

count the female line), the Countess Lucy looked well fed. A

discriminating nose she had for scents, prolonged, as if in quest of

them; her underlip protruded a narrow red shelf; her eyes were small,

with sandy tufts for eyebrows, and her jowl was heavy. Behind her (the

window looked on Grosvenor Square) stood Moll Pratt on the pavement,

offering violets for sale; and Mrs. Hilda Thomas, lifting her skirts,

preparing to cross the road. One was from Walworth; the other from

Putney. Both wore black stockings, but Mrs. Thomas was coiled in furs.

The comparison was much in Lady Rocksbier’s favour. Moll had more

humour, but was violent; stupid too. Hilda Thomas was mealy-mouthed, all

her silver frames aslant; egg-cups in the drawing-room; and the windows

shrouded. Lady Rocksbier, whatever the deficiencies of her profile, had

been a great rider to hounds. She used her knife with authority, tore

her chicken bones, asking Jacob’s pardon, with her own hands.

“Who is that driving by?” she asked Boxall, the butler.

“Lady Firtlemere’s carriage, my lady,” which reminded her to send a card

to ask after his lordship’s health. A rude old lady, Jacob thought. The

wine was excellent. She called herself “an old woman”—“so kind to lunch

with an old woman”—which flattered him. She talked of Joseph

Chamberlain, whom she had known. She said that Jacob must come and meet—

one of our celebrities. And the Lady Alice came in with three dogs on a

leash, and Jackie, who ran to kiss his grandmother, while Boxall brought

in a telegram, and Jacob was given a good cigar.

A few moments before a horse jumps it slows, sidles, gathers itself

together, goes up like a monster wave, and pitches down on the further

side. Hedges and sky swoop in a semicircle. Then as if your own body ran

into the horse’s body and it was your own forelegs grown with his that

sprang, rushing through the air you go, the ground resilient, bodies a

mass of muscles, yet you have command too, upright stillness, eyes

accurately judging. Then the curves cease, changing to downright hammer

strokes, which jar; and you draw up with a jolt; sitting back a little,

sparkling, tingling, glazed with ice over pounding arteries, gasping:

“Ah! ho! Hah!” the steam going up from the horses as they jostle

together at the cross-roads, where the signpost is, and the woman in the

apron stands and stares at the doorway. The man raises himself from the

cabbages to stare too.

So Jacob galloped over the fields of Essex, flopped in the mud, lost the

hunt, and rode by himself eating sandwiches, looking over the hedges,

noticing the colours as if new scraped, cursing his luck.

He had tea at the Inn; and there they all were, slapping, stamping,

saying, “After you,” clipped, curt, jocose, red as the wattles of

turkeys, using free speech until Mrs. Horsefield and her friend Miss

Dudding appeared at the doorway with their skirts hitched up, and hair

looping down. Then Tom Dudding rapped at the window with his whip. A

motor car throbbed in the courtyard. Gentlemen, feeling for matches,

moved out, and Jacob went into the bar with Brandy Jones to smoke with

the rustics. There was old Jevons with one eye gone, and his clothes the

colour of mud, his bag over his back, and his brains laid feet down in

earth among the violet roots and the nettle roots; Mary Sanders with her

box of wood; and Tom sent for beer, the half-witted son of the sexton—

all this within thirty miles of London.

Mrs. Papworth, of Endell Street, Covent Garden, did for Mr. Bonamy in

New Square, Lincoln’s Inn, and as she washed up the dinner things in the

scullery she heard the young gentlemen talking in the room next door.

Mr. Sanders was there again; Flanders she meant; and where an

inquisitive old woman gets a name wrong, what chance is there that she

will faithfully report an argument? As she held the plates under water

and then dealt them on the pile beneath the hissing gas, she listened:

heard Sanders speaking in a loud rather overbearing tone of voice:

“good,” he said, and “absolute” and “justice” and “punishment,” and “the

will of the majority.” Then her gentleman piped up; she backed him for

argument against Sanders. Yet Sanders was a fine young fellow (here all

the scraps went swirling round the sink, scoured after by her purple,

almost nailless hands). “Women”—she thought, and wondered what Sanders

and her gentleman did in THAT line, one eyelid sinking perceptibly as

she mused, for she was the mother of nine—three still-born and one deaf

and dumb from birth. Putting the plates in the rack she heard once more

Sanders at it again (“He don’t give Bonamy a chance,” she thought).

“Objective something,” said Bonamy; and “common ground” and something

else—all very long words, she noted. “Book learning does it,” she

thought to herself, and, as she thrust her arms into her jacket, heard

something—might be the little table by the fire—fall; and then stamp,

stamp, stamp—as if they were having at each other—round the room,

making the plates dance.

“To-morrow’s breakfast, sir,” she said, opening the door; and there were

Sanders and Bonamy like two bulls of Bashan driving each other up and

down, making such a racket, and all them chairs in the way. They never

noticed her. She felt motherly towards them. “Your breakfast, sir,” she

said, as they came near. And Bonamy, all his hair touzled and his tie

flying, broke off, and pushed Sanders into the arm-chair, and said Mr.

Sanders had smashed the coffee-pot and he was teaching Mr. Sanders—

Sure enough, the coffee-pot lay broken on the hearthrug.

“Any day this week except Thursday,” wrote Miss Perry, and this was not

the first invitation by any means. Were all Miss Perry’s weeks blank

with the exception of Thursday, and was her only desire to see her old

friend’s son? Time is issued to spinster ladies of wealth in long white

ribbons. These they wind round and round, round and round, assisted by

five female servants, a butler, a fine Mexican parrot, regular meals,

Mudie’s library, and friends dropping in. A little hurt she was already

that Jacob had not called.

“Your mother,” she said, “is one of my oldest friends.”

Miss Rosseter, who was sitting by the fire, holding the Spectator

between her cheek and the blaze, refused to have a fire screen, but

finally accepted one. The weather was then discussed, for in deference

to Parkes, who was opening little tables, graver matters were postponed.

Miss Rosseter drew Jacob’s attention to the beauty

Comments (0)