Psychology, Robert S. Woodworth [android based ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: Robert S. Woodworth

- Performer: -

Book online «Psychology, Robert S. Woodworth [android based ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author Robert S. Woodworth

Margaret F. Washburn, The Animal Mind, 2nd edition, 1917. John B. Watson, Behavior, 1914.

On child psychology:

Norsworthy and Whitley, The Psychology of Childhood, 1918.

On abnormal psychology:

A. J. Rosanoff, Manual of Psychiatry, 5th edition, 1920.

On applied psychology:

Hollingworth and Poffenberger, Applied Psychology, 1917.

On individual psychology, parts of:

E. L. Thorndike, Educational Psychology, Briefer Course, 1914, Daniel Starch, Educational Psychology, 1919.

{21}

REACTIONS

Having the field of psychology open before us, the next question is, where to commence operations. Shall we begin with memory, imagination and reasoning, or with will, character and personality, or with motor activity and skill, or with feelings and emotions, or with sensation and perceptions? Probably the higher forms of mental activity seem most attractive, but we may best leave complicated matters till later, and agree to start with the simplest sorts of mental performance. Thus we may hope to learn at the outset certain elementary facts which will later prove of much assistance in unraveling the more complex processes.

Among the simplest processes are sensations and reflexes, and we might begin with either. The introspective psychologists usually start with sensations, because their great object is to describe consciousness, and they think of sensations as the chief elements of which consciousness is composed. The behaviorists would prefer to start with reflexes, because they conceive of behavior as composed of these simple motor reactions.

Without caring to attach ourselves exclusively to either introspectionism or behaviorism, we may take our cue just here from the behaviorists, because we shall find the facts of motor reaction more widely useful in our further studies than the facts of sensation, and because the facts of {22} sensation fit better into the general scheme of reactions than the facts of reaction fit into any general scheme based on sensation.

A reaction is a response to a stimulus. The response, in the simplest cases, is a muscular movement, and is called a "motor response". The stimulus is any force or agent that, acting upon the individual, arouses a response.

If I start at a sudden noise, the noise is the stimulus, and the forcible contraction of my muscles is the response. If my old friend's picture brings tears to my eyes, the picture (or the light reflected from it) is the stimulus, and the flow of tears is the response, here a "glandular" instead of a motor response.

The Reaction Time ExperimentOne of the earliest experiments to be introduced into psychology was that on reaction time, conducted as follows: The experimenter tells his "subject" (the person whose reaction is to be observed) to be ready to make a certain movement as promptly as possible on receiving a certain stimulus. The response prescribed is usually a slight movement of the forefinger, and the stimulus may be a sound, a flash of light, a touch on the skin, etc. The subject knows in advance exactly what stimulus is to be given and what response he has to make, and is given a "Ready!" signal a few seconds before the stimulus. With so simple a performance, the reaction time is very short, and delicate apparatus must be employed to measure it. The "chronoscope" or clock used to measure the reaction time reads to the hundredth or thousandth of a second, and the time is found to be about .15 sec. in responding to sound or touch, about .18 sec. in responding to light.

Even the simple reaction time varies, however, from one {23} individual to another, and from one trial to another. Some persons can never bring their record much below the figures stated, while a few can get the time down to .10 sec, which is about the limit of human ability. Every one is bound to vary from trial to trial, at first widely, after practice between narrow limits, but always by a few hundredths of a second at the least. It is curious to find the elementary fact of variability of reaction present in such a simple performance.

What we have been describing is known as the "simple reaction", in distinction from other experiments that demand more of the subject. In the "choice reaction", there are two stimuli and the subject may be required to react to the one with the right hand and to the other with the left; for example, if a red light appears he must respond with the right hand, but if a green light appears, with the left. Here he cannot allow himself to become keyed up to as high a pitch as in the simple reaction, for if he does he will make many false reactions. Therefore, the choice reaction time is longer than the simple reaction time--about a tenth of a second longer.

The "associative reaction" time is longer still. Here the subject must name any color that is shown, or read any letter that is shown, or respond to the sight of any number by calling out the next larger number, or respond to any suitable word by naming its opposite. He cannot be so well prepared as for the simple, or choice reaction, since he doesn't know exactly what the stimulus is going to be; also, the brain process is more complex here; so that the reaction time is longer, about a tenth of a second longer, at the best, than the choice reaction. It may run up to two or three seconds, even in fairly simple cases, while if any serious thinking or choosing has to be done, it runs into many seconds and even into minutes. Here the brain process is very {24} complex and involves a series of steps before the required motor response can be made.

These laboratory experiments can be paralleled by many everyday performances. The runner starting at the pistol shot, after the preparatory "Ready! Set!", and the motorman applying the brakes at the expected sound of the bell, are making "simple" reactions. The boxer, dodging to the right or the left according to the blow aimed at him by his adversary, is making choice reactions, and this type is very common in all kinds of steering, handling tools and managing machinery. Reading words, adding numbers, and a large share of simple mental performances, are essentially associative reactions. In most cases from ordinary life, the preparation is less complete than in the laboratory experiments, and the reaction time is accordingly longer.

Reflex ActionThe simple reaction has some points of resemblance with the "reflex", which, also, is a prompt motor response to a sensory stimulus. A familiar example is the reflex wink of the eyes in response to anything touching the eyeball, or in response to an object suddenly approaching the eye. This "lid reflex" is quicker than the quickest simple reaction, taking about .05 second. The knee jerk or "patellar reflex", aroused by a blow on the patellar tendon just below the knee when the knee is bent and the lower leg hanging freely, is quicker still, taking about .03 second. The reason for this extreme quickness of the reflex will appear as we proceed. However, not every reflex is as quick as those mentioned, and some are slower than the quickest of the simple reactions.

A few other examples of reflexes may be given. The "pupillary reflex" is the narrowing of the pupil of the eye {25} in response to a bright light suddenly shining into the eye. The "flexion reflex" is the pulling up of the leg in response to a pinch, prick or burn on the foot. Coughing and sneezing are like this in being protective reflexes, and the scratching of the dog belongs here also.

There are many internal reflexes: movements of the stomach and intestines, swallowing and hiccoughing, widening and narrowing of the arteries resulting in flushing and paling of the skin. These are muscular responses; and there are also glandular reflexes, such as the discharge of saliva from the salivary glands into the mouth, in response to a tasting substance, the flow of the gastric juice when food reaches the stomach, the flow of tears when a cinder gets into the eye. There are also inhibitory reflexes, such as the momentary stoppage of breathing in response to a dash of cold water. All in all, a large number of reflexes are to be found.

Most reflexes can be seen to be useful to the organism. A large proportion of them are protective in one way or another, while others might be called regulative, in that they adjust the organism to the conditions affecting it.

Now comparing the reflex with the simple reaction, we see first that the reflex is more deep-seated in the organism, and more essential to its welfare. The reflex is typically quicker than the simple reaction. The reflex machinery does not need a "Ready" signal, nor any preparation, but is always ready for business. (The subject in a simple reaction experiment would not make the particular finger movement that he makes unless he had made ready for that movement.) The attachment of a certain response to a certain stimulus, rather arbitrary and temporary in the simple reaction, is inherent and permanent in the reflex. Reflex action is involuntary and often entirely unconscious.

Reflexes, we said, are permanent. That is because they {26} are native or inherent in the organism. You can observe them in the new-born child. The reflex connection between stimulus and response is something the child brings with him into the world, as distinguished from what he has to acquire through training and experience. He does acquire, as he grows up, a tremendous number of habitual responds that become automatic and almost unconscious, and these "secondary automatic" reactions resemble reflexes pretty closely. Grasping for your hat when you feel the wind taking it from your head is an example. These acquired reactions never reach the extreme speed of the quickest reflexes, but at best may have about the speed of the simple reaction. Though often useful enough, they are not so fundamentally necessary as the reflexes. The reflex connection of stimulus and response is something essential, native, closely knit, and always ready for action.

The Nerves in Reflex ActionSeeing that the response, in reflex action, is usually made by a muscle or gland lying at some distance from the sense organ that receives the stimulus--as, in the case of the flexion reflex, the stimulus is applied to the skin of the hand (or foot), while the response is made by muscles of the limb generally--we have to ask what sort of connection exists between the stimulated organ and the responding organ, and we turn to physiology and anatomy for our answer. The answer is that the nerves provide the connection. Strands of nerve extend from the sense organ to the muscle.

But the surprising fact is that the nerves do not run directly from the one to the other. There is no instance in the human body of a direct connection between any sense organ and any muscle or gland. The nerve path from sense organ to muscle always leads through a nerve center. One {27} nerve, called the sensory nerve, runs from the sense organ to the nerve center, and another, the motor nerve, runs from the center to the muscle; and the only connection between the sense organ and the muscle is this roundabout path through the nerve center. The path consists of three parts, sensory nerve, center, and motor nerve, but, taken as a whole, it is called the reflex arc, both the words, "reflex" and "arc", being suggested by the indirectness of the connection.

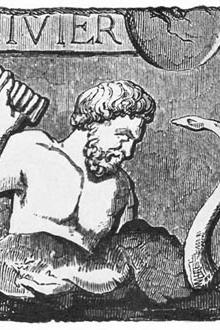

Fig. 1.--The connection from the back of the hand, which is receiving a stimulus, and the arm muscle which makes the response. The nerve center is indicated by the dotted lines.

The nervous system resembles a city telephone system. What passes along the nerve is akin to the electricity that {28} passes along the telephone wire; it is

Comments (0)