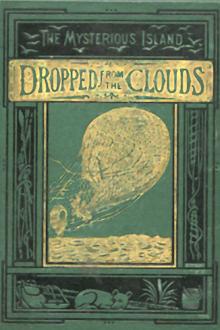

The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [most popular ebook readers txt] 📗

- Author: Jules Verne

- Performer: 0812972120

Book online «The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [most popular ebook readers txt] 📗». Author Jules Verne

Meantime the night advanced; and it was about 2 o’clock when Pencroff was suddenly aroused from a deep sleep by finding himself vigorously shaken.

“What’s the matter?” he cried, rousing and collecting himself with the quickness peculiar to sailors.

The reporter was bending over him and saying:—

“Listen, Pencroff, listen!”

The sailor listened, but could hear no sounds other than those caused by the gusts.

“It is the wind,” he said.

“No,” answered Spilett, listening again, “I think I heard—”

“What?”

“The barking of a dog!”

“A dog!” cried Pencroff, springing to his feet.

“Yes—the barking—”

“Impossible!” answered the sailor. “How, in the roarings of the tempest—”

“Wait—listen,” said the reporter.

Pencroff listened most attentively, and at length, during a lull, he thought he caught the sound of distant barking.

“Is it?” asked the reporter, squeezing the sailor’s hand.

“Yes—yes!” said Pencroff.

“It is Top! It is Top!” cried Herbert, who had just wakened, and the three rushed to the entrance of the Chimneys.

They had great difficulty in getting out, as the wind drove against them with fury, but at last they succeeded, and then they were obliged to steady themselves against the rocks. They were unable to speak, but they looked about them. The darkness was absolute. Sea, sky, and earth, were one intense blackness. It seemed as if there was not one particle of light diffused in the atmosphere.

For some moments the reporter and his two companions stood in this place, beset by the gusts, drenched by the rain, blinded by the sand. Then again, in the hush of the storm, they heard, far away, the barking of a dog. This must be Top. But was he alone or accompanied? Probably alone, for if Neb had been with him, the negro would have hastened, at once, to the Chimneys.

The sailor pressed the reporter’s hand in a manner signifying that he was to remain without, and then returning to the corridor, emerged a moment later with a lighted fagot, which he threw into the darkness, at the same time whistling shrilly. At this signal, which seemed to have been looked for, the answering barks came nearer, and soon a dog bounded into the corridor, followed by the three companions. An armful of wood was thrown upon the coals, brightly lighting up the passage.

“It is Top!” cried Herbert.

It was indeed Top, a magnificent Anglo-Norman, uniting in the cross of the two breeds those qualities—swiftness of foot and keenness of scent—indispensable in coursing dogs. But he was alone! Neither his master nor Neb accompanied him.

It seemed inexplicable how, through the darkness and storm, the dog’s instinct had directed him to the Chimneys, a place he was unacquainted with. But still more unaccountable was the fact that he was neither fatigued nor exhausted nor soiled with mud or sand. Herbert had drawn him towards him, patting his head; and the dog rubbed his neck against the lad’s hands.

“If the dog is found, the master will be found also,” said the reporter.

“God grant it!” responded Herbert. “Come, let us set out. Top will guide us!”

Pencroff made no objection. He saw that the dog’s cunning had disproved his conjectures.

“Let us set out at once,” he said; and covering the fire so that it could be relighted on their return, and preceded by the dog, who seemed to invite their departure, the sailor, having gathered up the remnants of the supper, followed by the reporter and Herbert, rushed into the darkness.

The tempest, then in all its violence, was, perhaps, at its maximum intensity. The new moon had not sufficient light to pierce the clouds. It was difficult to follow a straight course. The better way, therefore, was to trust to the instinct of Top; which was done. The reporter and the lad walked behind the dog, and the sailor followed after. To speak was impossible. The rain, dispersed by the wind, was not heavy, but the strength of the storm was terrible.

Fortunately, as it came from the southeast, the wind was at the back of the party, and the sand, hurled from behind, did not prevent their march. Indeed, they were often blown along so rapidly as nearly to be overthrown. But they were sustained by a great hope. This time, at least, they were not wandering at random. They felt, no doubt, that Neb had found his master and had sent the faithful dog to them. But was the engineer living, or had Neb summoned his companions only to render the last services to the dead?

After having passed the smooth face of rock, which they carefully avoided, the party stopped to take breath. The angle of the cliff sheltered them from the wind, and they could breathe freely after this tramp, or rather race, of a quarter of an hour. They were now able to hear themselves speak, and the lad having pronounced the name of Smith, the dog seemed to say by his glad barking that his master was safe.

“Saved! He is saved! Isn’t he, Top?” repeated the boy. And the dog barked his answer.

It was half-past 2 when the march was resumed. The sea began to rise, and this, which was a spring tide backed up by the wind, threatened to be very high. The tremendous breakers thundered against the reef, assailing it so violently as probably to pass completely over the islet, which was invisible. The coast was no longer sheltered by this long breakwater, but was exposed to the full fury of the open sea.

After the party were clear of the precipice the storm attacked them again with fury. Crouching, with backs still to the wind, they followed Top, who never hesitated in his course. Mounting towards the north, they had upon their right the endless line of breakers deafening them with its thunders, and upon their left a region buried in darkness. One thing was certain, that they were upon an open plain, as the wind rushed over them without rebounding as it had done from the granite cliffs.

By 4 o’clock they estimated the distance travelled as eight miles. The clouds had risen a little, and the wind was drier and colder. Insufficiently clad, the three companions suffered cruelly, but no murmur passed their lips. They were determined to follow Top wherever he wished to lead them.

Towards 5 o’clock the day began to break. At first, overhead, where some grey shadowings bordered the clouds, and presently, under a dark band a bright streak of light sharply defined the sea horizon. The crests of the billows shone with a yellow light and the foam revealed its whiteness. At the same time, on the left, the hilly parts of the shore were confusedly defined in grey outlines upon the blackness of the night. At 6 o’clock it was daylight. The clouds sped rapidly overhead. The sailor and his companions were some six miles from the Chimneys, following a very flat shore, bordered in the offing by a reef of rocks whose surface only was visible above the high tide. On the left the country sloped up into downs bristling with thistles, giving a forbidding aspect to the vast sandy region. The shore was low, and offered no other resistance to the ocean than an irregular chain of hillocks. Here and there was a tree, leaning its trunks and branches towards the west. Far behind, to the southwest, extended the borders of the forest.

At this moment Top gave unequivocal signs of excitement. He ran ahead, returned, and seemed to try to hurry them on. The dog had left the coast, and guided by his wonderful instinct, without any hesitation had gone among the downs. They followed him through a region absolutely devoid of life.

The border of the downs, itself large, was composed of hills and hillocks, unevenly scattered here and there. It was like a little Switzerland of sand, and nothing but a dog’s astonishing instinct could find the way.

Five minutes after leaving the shore the reporter and his companions reached a sort of hollow, formed in the back of a high down, before which Top stopped with a loud bark. The three entered the cave.

Neb was there, kneeling beside a body extended upon a bed of grass—

It was the body of Cyrus Smith.

CHAPTER VIII.IS CYPRUS SMITH ALIVE?—NEB’S STORY—FOOTPRINTS —AN INSOLUBLE QUESTION—THE FIRST WORDS OF SMITH—COMPARING THE FOOTPRINTS—RETURN TO THE CHIMNEYS—PENCROFF DEJECTED.

Neb did not move. The sailor uttered one word.

“Living!” he cried.

The negro did not answer. Spilett and Pencroff turned pale. Herbert, clasping his hands, stood motionless. But it was evident that the poor negro, overcome by grief, had neither seen his companions nor heard the voice of the sailor.

The reporter knelt down beside the motionless body, and, having opened the clothing, pressed his ear to the chest of the engineer. A minute, which seemed an age, passed, daring which he tried to detect some movement of the heart.

Neb raised up a little, and looked on as if in a trance. Overcome by exhaustion, prostrated by grief, the poor fellow was hardly recognizable. He believed his master dead.

Gideon Spilett, after a long and attentive examination, rose up.

“He lives!” he said.

Pencroff, in his turn, knelt down beside Cyrus Smith; he also detected some heartbeats, and a slight breath issuing from the lips of the engineer. Herbert, at a word from the reporter, hurried in search of water. A hundred paces off he found a clear brook swollen by the late rains and filtered by the sand. But there was nothing, not even a shell, in which to carry the water; so the lad had to content himself with soaking his handkerchief in the stream, and hastened back with it to the cave.

Happily the handkerchief held sufficient for Spilett’s purpose, which was simply to moisten the lips of the engineer. The drops of fresh water produced an instantaneous effect. A sigh escaped from the breast of Smith, and it seemed as if he attempted to speak.

“We shall save him,” said the reporter. Neb took heart at these words. He removed the clothing from his master to see if his body was anywhere wounded. But neither on his head nor body nor limbs was there a bruise or even a scratch, an astonishing circumstance, since he must have been tossed about among the rocks; even his hands were uninjured, and it was difficult to explain how the engineer should exhibit no mark of the efforts which he must have made in getting over the reef.

But the explanation of this circumstance would come later, when Cyrus Smith could speak. At present, it was necessary to restore his consciousness, and it was probable that this result could be accomplished by friction. For this purpose they mode use of the sailor’s pea-jacket. The engineer, warmed by this rude rubbing, moved his arms slightly, and his breathing began to be more regular. He was dying from exhaustion, and, doubtless, had not the reporter and his companions arrived, it would have been all over with Cyrus Smith.

“You thought he was dead?” asked the sailor.

“Yes, I thought so,” answered Neb. “And if Top had not found you and brought you back, I would have buried my master and died beside him.”

The engineer had had a narrow escape!

Then Neb told them what had happened. The day before, after having left the Chimneys at day-break, he had followed along the coast in a direction due north, until he reached that part of the beach which he had already visited. There, though, as he said, without hope of success, he searched the shore, the rocks, the sand for any marks that could guide him, examining most carefully that part which was above high-water mark, as below that point the ebb and flow of the tide would have effaced all traces. He did not hope to find his master living. It was the discovery of the body which he sought, that he might bury it with his own hands. He searched a long time, without success. It seemed as if nothing human had ever been upon that desolate shore. Of the millions of shell-fish lying out of reach of

Comments (0)