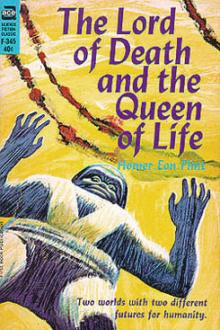

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

- Performer: -

Book online «The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author Homer Eon Flint

Said Myrin: “You are accustomed to the idea of government. We, however, have outgrown it.

“If you stop to think, you will agree that the purpose of government is to maintain peace, on the one hand, and to wage war, on the other. Now, as to war—we haven’t even separate nations, any more. So we have no wars. And as for internal conflict—why should we ever quarrel, when each of us is assured all that he can possibly want?”

“So you have abolished government?”

“A very long time ago. You on the earth will do the same, as soon as your people have been educated up to the point of trusting each other.”

“You haven’t even a congress, then?”

Myrin shook her head. “All questions such as a congress would deal with, were settled ages ago. You must remember that the material features of our civilization have not changed for thousands of generations. The only questions that come up now are purely personal ones, which each must settle for himself.”

Van Emmon, as before, was not at all satisfied. “You say that machinery does your work for you. I presume you do not mean that literally; there must be some duties which cannot be performed without human direction, at least. How do you get these duties accomplished, if you have no government to compel your people to do them?”

Myrin looked at a loss, either for the answer itself or for the most suitable words. Estra gave the reply: “Every device we possess is absolutely automatic. There is not one item in the materials we use but that was constructed, exactly as you see it now, many thousands of years ago.”

Smith was incredulous. “Do you mean to say that those little glass pews have been in use all that time?”

Estra nodded, smiling gently at the engineer’s amazement. “Like everything else, they were built to last. You must remember that we do not have anything like an ‘investment,’ here; we do not have to consider the question of ‘getting our capital back.’ So, if any further improvements were to be made, they also would be done in a permanent fashion.”

Billie gave an exclamation of bewilderment. “I don’t understand! You say that nothing new has been built, or even replaced, for centuries. How do you take care of your increase in population?” thinking of the great crowd that had just left.

Myrin was the one who answered this. As she did so, she got slowly to her feet; and speaking with the utmost care, watched to be sure that the four understood her:

“Ever since the roof was put on, our increase of population has been exactly balanced by our death rate!”

The four followed their guides in silence as they led the way into the plaza. Now, the space was alive with Venusians. The little cages were everywhere floating about in the air; some of the people were laboriously shifting themselves into their aircraft; others were guiding their “pews” direct to nearby houses. The visitors got plenty of curious stares from these quiet miracle-workers, who seemed vastly more at home in the air than on the ground. “As thick as flies,” Van Emmon commented.

Estra and Myrin, walking very slowly, took them to a side street, where two of the cigar-shaped cars were standing. Billie and Smith got in with Estra, while Van Emmon and the doctor were given seats beside the Venusian woman. The two cars were connected by telephone, so that in effect the two parties were one.

By this time, the visitors had become so accustomed to the transparent material that they felt no uneasiness as the ground receded below them. Smith, especially, was tremendously impressed with Estra’s declaration that the glass was, except for appearance, nothing more nor less than an extremely strong, steel alloy.

Propelled by the unexplained forces which the two drivers controlled by means of buttons in black cases, the two cars began to thread their way through the great roof-columns; and as they proceeded, the four grew more and more amazed at the great extent of the city. For miles upon miles that heterogeneous collection of buildings stretched, unbroken and without system, until the eye tired of trying to make out the limits of it.

“What is the name of this city?” asked Billie, secretly hoping that it might bear some resemblance to “New York.” It struck her fancy to assume that this supermetropolis represented what Gotham, in time, might become.

Estra did not take his attention from what he was doing, but answered as readily as ever. “I do not blame you for mistaking this for a city. The fact is, however, that we have no such thing.”

Billie stared at him helplessly. “You’ve abolished cities, too?”

“Not exactly. In the same sense that we have abolished nations, yes. Likewise we have abolished states, also counties. Neither have we such a thing as ‘the country,’ now.

“My friends, Venus is simply one immense city.”

IX THE SURVIVAL OF ALLSomehow all four were unwilling to press this question. It did not seem possible that Estra was right, or, if he was, that they could possibly understand his explanation, should he give it. The cars flew side by side for perhaps a hundred miles, while the visitors put in the time in examining the landscape with the never-ending interest of all aeronauts.

Here and there, in that closely-packed surface, a particularly large building was to be noted every half mile or so. “Factories?” asked Billie of Estra, but he shook his head.

“I’ll show you factories later on,” said he. “What you see are schools.” But most observers would have considered the structures severely plain for their purpose.

After a long silence: “I’m still looking for streams,” said Van Emmon to Myrin. “Are your rivers as large as ours?”

“We have no rivers,” was the calm reply. “Rivers are entirely too wasteful of water. All our drainage is carried off through underground canals.”

“You haven’t done away with your oceans, too, have you?” the geologist asked, rather sarcastically. But he was scarcely prepared for the reply he got.

“No; we couldn’t get along without them, I am afraid. However, we did the best we could in their case.” And without signaling to Estra she dove the machine towards the ground. Smith looked for the telephone wires to snap, but Estra seemed to know, and instantly followed Myrin’s lead. The doctor noticed, and wondered all the more.

And then came another surprise. As the machines neared the surface, a familiar odor floated in through the open windows of the aircraft; and the four found themselves looking at each other for signs of irrationality. A moment, and they saw that they were not mistaken.

For, although that kaleidoscopic expanse of buildings showed not the slightest break, yet they were now located on the sea. The houses were packed as closely together as anywhere; apparently all were floating, yet not ten square yards of open sea could be seen in any one spot.

Van Emmon almost forgot his resentment in his growing wonder. “That gets me, Myrin! Those houses seem to be merely floating, yet I see no motion whatever! Why are there no waves?”

The doctor snorted. “Shame on you, Van! Don’t let our friends think that you’re an absolute ignoramus.” He added: “Venus has no moon, and no wind, at least under the roof. Therefore, no waves.”

Smith put in: “That being the case, there is no chance to start a wave-motor industry here. Neither,” as he thought further, “neither for water-power. Having no rain in your mountains, Estra, where do you get your power?”

But it was Myrin who answered. “I suppose you are all familiar with radium? It is nothing more or less than condensed sunlight, which in turn is simply electromagnetic waves; although it may take your scientists a good many centuries to reach that conclusion.

“Well, every particle of the material which composes this planet, contains radioactivity of some sort; and we long ago discovered a way to release it and use it. One pound of solid granite yields enough energy to—well, a great deal of power.”

They had now been flying for two hours, and still no end to that thickly-housed, ever different appearance of the ground. Also, although they saw a great many birds, they noted no animals. Finally, Billie could hold in no longer.

“Are we to understand,” she demanded of Estra, “that the whole of this planet is as densely populated as we see it?”

“Just that,” replied the Venusian. “Why not? The roof makes our climate uniform from pole to pole, while our buildings are such that, whether on land or on sea, they are equally livable.”

“But—Estra!” expostulated the girl. “Venus is nearly as big as the earth. And it looks to be as thickly populated as—as Rhode Island! Why, you must have a colossal population; let me see.” And she scribbled away in her memorandum book.

But both Smith and the doctor had already worked it out. They looked up, blinking dazedly.

“Over three hundred billion,” murmured the doctor, as though dizzy.

The Venusian checked Smith’s correction with, “You dropped one cipher, doctor. There are three and a half trillion of us!”

“Good lord!” whispered Van Emmon, all his antagonism gone for the moment. And again the explorers were silent for a long time.

By and by, however—“We have just seen what it meant, there on Mercury,” said the doctor, in a low voice, “for the principle of ‘the survival of the fit’ to be carried to its logical end; for who is to decide what is fitness, save the fittest? One man, apparently, outlived every one else on the planet, and then he also died.

“But here you have gone the limit in the other direction. Of course, we might have known that you long ago abolished poverty, unearned wealth, pestilence, drunkenness and the other causes of premature death; but as for three and a half trillion!”

“Nevertheless,” remarked Myrin, “every last one of us, once born, lives to die of old age; and in most cases this means several hundred of your years.”

Smith involuntarily rubbed his eyes; and they all laughed, a nervous sort of a laugh which left the visitors still in doubt as to their senses, and their guides’ sanity. Van Emmon’s suspicions came back with a rush, and he burst out:

“Say—you’ll excuse me, but I can’t swallow this! Here you’ve shown us houses as thick as leaves; not a sign of a farm, much less an orchard! No vegetation at all, except for a few flowers!

“Three and a half trillion! All right; let it go at that!” Out came his chin, and he brought one fist down upon the other as though he were cracking rocks with a hammer, and with every blow he uttered a word:

“How—do—you—feed—them—all?”

X LOAVES AND FISHESWithout a word Myrin drove her machine toward the ground, and, as before, Estra followed despite the lack of any visible signal. Within a minute the two machines had come to rest, softly and without disturbance, on the roof of a handsome building, much like an apartment house. There was the usual transparent elevator, and a minute later the four were being introduced to the occupants of a typical Venusian house.

These two people, apparently man and wife, did not need to be told why the explorers had been brought there. They led the way from the dimly lighted hallway in which the elevator had stopped, into a group of brightly decorated rooms. Here the four were given seats in

Comments (0)