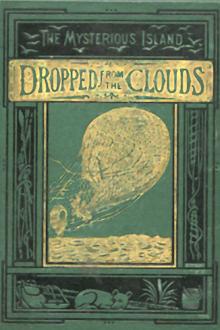

The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [most popular ebook readers txt] 📗

- Author: Jules Verne

- Performer: 0812972120

Book online «The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [most popular ebook readers txt] 📗». Author Jules Verne

The engineer proceeded in this manner. The sealskin bellows, furnished with a pipe of refractory earth (an earth difficult of fusion), which had previously been prepared at the pottery, was set up close to the heap of ore. And, moved by a mechanism consisting of a frame, fibre-cords, and balance-weight, it injected into the mass a supply of air, which, by raising the temperature, assisted the chemical transformation which would give the pure metal.

The operation was difficult. It took all the patience and ingenuity of the colonists to conduct it properly; but finally it succeeded, and the result was a pig of iron in a spongy state, which must be cut and forged in order to expel the liquified gangue. It was evident that these self-constituted smiths wanted a hammer, but they were no worse off than the first metallurgist, and they did as he must have done.

The first pig, fastened to a wooden handle, served as a hammer with which to forge the second upon an anvil of granite, and they thus obtained a coarse metal, but one which could be utilized.

At length, after much trouble and labor, on the 25th of April, many bars of iron had been forged and turned into crowbars, pincers, pickaxes, mattocks, etc., which Pencroff and Neb declared to be real jewels.

But in order to be in its most serviceable state, iron must be turned into steel. Now steel, which is a combination of iron and carbon, is made in two ways: first from cast iron, by decarburetting the molten metal, which gives natural or puddled steel; and, second, by the method of cementation, which consists in carburetting malleable iron. As the engineer had iron in a pure state, he chose the latter method, and heated the metal with powdered charcoal in a crucible made from refractory earth.

This steel, which was malleable hot and cold, he worked with the hammer. And Neb and Pencroff, skillfully directed, made axe-heads, which, heated red-hot and quickly plunged in cold water, took an excellent temper.

Other instruments, such as planes and hatchets, were rudely fashioned, and bands of steel were made into saws and chisels; and from the iron, mattocks, shovels, pickaxes, hammers, nails, etc., were manufactured.

By the 5th of May the first metallurgic period was ended, the smiths returned to the Chimneys, and new work would soon authorize their assumption of a new title.

CHAPTER XVI.THE QUESTION OF A DWELLING DISCUSSED AGAIN—PENCROFF’S IDEAS—AN EXPLORATION TO THE NORTH OF THE LAKE—THE WESTERN BOUNDARY OF THE PLATEAU—THE SERPENTS—THE OUTLET OF THE LAKE—TOP’S ALARM—TOP SWIMMING—A FIGHT UNDER WATER—THE DUGONG.

It was the 6th of May, corresponding to the 6th of November in the Northern Hemisphere. For some days the sky had been cloudy, and it was important to make provision against winter. However, the temperature had not lessened much, and a centigrade thermometer transported to Lincoln Island would have averaged 10° or 12° above zero. This would not be surprising, since Lincoln Island, from its probable situation in the Southern Hemisphere, was subject to the same climatic influences as Greece or Sicily in the Northern. But just as the intense cold in Greece and Sicily sometimes produces snow and ice, so, in the height of winter, this island would probably experience sudden changes in the temperature against which it would be well to provide.

At any rate, if the cold was not threatening, the rainy season was at hand, and upon this desolate island, in the wide Pacific, exposed to all the inclemency of the elements, the storms would be frequent, and, probably, terrible.

The question of a more comfortable habitation than the Chimneys ought, therefore, to be seriously considered, and promptly acted upon.

Pencroff having discovered the Chimneys, naturally had a predilection for them; but he understood very well that another place must be found. This refuge had already been visited by the sea, and it would not do to expose themselves to a like accident.

“Moreover,” added Smith, who was discussing these things with his companions, “there are some precautions to take.”

“Why? The island is not inhabited,” said the reporter.

“Probably not,” answered the engineer, “although we have not yet explored the whole of it; but if there are no human beings, I believe dangerous beasts are numerous. So it will be better to provide a shelter against a possible attack, than for one of us to be tending the fire every night. And then, my friends, we must foresee everything. We are here in a part of the Pacific often frequented by Malay pirates—”

“What, at this distance from land?” exclaimed Herbert.

“Yes, my boy, these pirates are hardy sailors as well as formidable villains, and we must provide for them accordingly.”

“Well,” said Pencroff, “we will fortify ourselves against two and four-footed savages. But, sir, wouldn’t it be as well to explore the island thoroughly before doing anything else?”

“It would be better,” added Spilett; “who knows but we may find on the opposite coast one or more of those caves which we have looked for here in vain.”

“Very true,” answered the engineer, “but you forget, my friends, that we must be somewhere near running water, and that from Mount Franklin we were unable to see either brook or river in that direction. Here, on the contrary, we are between the Mercy and Lake Grant, which is an advantage not to be neglected. And, moreover, as this coast faces the east, it is not as exposed to the trade winds, which blow from the northwest in this hemisphere.”

“Well, then, Mr. Smith,” replied the sailor, “let us build a house on the edge of the lake. We are no longer without bricks and tools. After having been brickmakers, potters, founders, and smiths, we ought to be masons easily enough.”

“Yes, my friend; but before deciding it will be well to look about. A habitation all ready made would save us a great deal of work, and would, doubtless, offer a surer retreat, in which we would be safe from enemies, native as well as foreign?”

“But, Cyrus,” answered the reporter, “have we not already examined the whole of this great granite wall without finding even a hole?”

“No, not one!” added Pencroff. “If we could only dig a place in it high out of reach, that would be the thing! I can see it now, on the part overlooking the sea, five or six chambers—”

“With windows!” said Herbert, laughing.

“And a staircase!” added Neb.

“Why do you laugh?” cried the sailor. “Haven’t we picks and mattocks? Cannot Mr. Smith make powder to blow up the mine. You will be able, won’t you, sir, to make powder when we want it?”

The engineer had listened to the enthusiastic sailor developing these imaginative projects. To attack this mass of granite, even by mining, was an Herculean task, and it was truly vexing that nature had not helped them in their necessity. But he answered Pencroff, by simply proposing to examine the wall more attentively, from the mouth of the river to the angle which ended it to the north. They therefore went out and examined it most carefully for about two miles. But everywhere it rose, uniform and upright, without any visible cavity. The rock-pigeons flying about its summit had their nests in holes drilled in the very crest, or upon the irregularly cut edge of the granite.

To attempt to make a sufficient excavation in such a massive wall even with pickaxe and powder was not to be thought of. It was vexatious enough. By chance, Pencroff had discovered in the Chimneys, which must now be abandoned, the only temporary, habitable shelter on this part of the coast.

When the survey was ended the colonists found themselves at the northern angle of the wall, where it sunk by long declivities to the shore. From this point to its western extremity it was nothing more than a sort of talus composed of stones, earth, and sand bound together by plants, shrubs, and grass, in a slope of about 45°. Here and there the granite thrust its sharp points out from the cliff. Groups of trees grew over these slopes and there was a thin carpet of grass. But the vegetation extended but a short distance, and then the long stretch of sand, beginning at the foot of the talus, merged into the beach.

Smith naturally thought that the over flow of the lake fell in this direction, as the excess of water from Red Creek must be discharged somewhere, and this point had not been found less on the side already explored, that is to say from the mouth of the creek westward as far as Prospect Plateau.

The engineer proposed to his companions that they clamber up the talus and return to the Chimneys by the heights, exploring the eastern and western shores of the lake. The proposition was accepted, and, in a few minutes, Herbert and Neb had climbed to the plateau, the others following more leisurely.

Two hundred feet distant the beautiful sheet of water shone through the leaves in the sunlight. The landscape was charming. The trees in autumn tints, were harmoniously grouped. Some huge old weatherbeaten trunks stood out in sharp relief against the green turf which covered the ground, and brilliant cockatoos, like moving, prisms, glanced among the branches, uttering their shrill screams.

The colonists, instead of proceeding directly to the north bank of the lake, bore along the edge of the plateau, so as to come back to the mouth of the creek, on its left bank. It was a circuit of about a mile and a half. The walk was easy, as the trees, set wide apart, left free passage between them. They could see that the fertile zone stopped at this point, and that the vegetation here, was less vigorous than anywhere between the creek and the Mercy.

Smith and his companions moved cautiously over this unexplored neighborhood. Bows and arrows and iron-pointed sticks were their sole weapons. But no beast showed itself, and it was probable that the animals kept to the thicker forests in the south. The colonists, however, experienced a disagreeable sensation in seeing Top stop before a huge serpent 14 or 15 feet long. Neb killed it at a blow. Smith examined the reptile, and pronounced it to belong to the species of diamond-serpents eaten by the natives of New South Wales and not venomous, but it was possible others existed whose bite was mortal, such as the forked-tail deaf viper, which rise up under the foot, or the winged serpents, furnished with two ear-like appendages, which enable them to shoot forward with extreme rapidity. Top having gotten over his surprise, pursued these reptiles with reckless fierceness, and his master was constantly obliged to call him in.

The mouth of Red Creek, where it emptied into the lake, was soon reached. The party recognized on the opposite bank the point visited on their descent from Mount Franklin. Smith ascertained that the supply of water from the creek was considerable; there therefore must be an outlet for the overflow somewhere. It was this place which must be found, as, doubtless, it made a fall which could be utilized as a motive power.

The colonists, strolling along, without, however, straying too far from each other, began to follow round the bank of the lake, which was very abrupt. The water was full of fishes, and Pencroff promised himself soon to manufacture some apparatus with which to capture them.

It was necessary first to double the point at the northeast. They had thought that the discharge would be here, as the water flowed close to the edge of the plateau. But as it was not here, the colonists continued along the bank, which, after a slight curve, followed parallel with the sea-shore.

On this side the bank was less wooded, but clumps of trees, here and there, made a picturesque landscape. The whole extent of the

Comments (0)